August 29, 2018

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

Aug. 29, 2018

“Wed. 28th. – Drisly rain and cold,” Olson wrote in his August 1918 diary. “Mr. Kint and is son arrived from seward this afternoon. goats out all night.”

“Thurs. 29th. – goats cam ome – 12:30 P.M. Mr. Kint Working on the Cabbin fixing at up. Drisly rain all night and all day.”

No doubt Olson was restless Wednesday, Aug. 28th, as he gazed off and on out to sea waiting for the Kents to arrive in their dory. The trip would take the artist and his son longer than they had planned. After their engine conked out, they dropped it off at George Hogg’s camp along the western shore of Resurrection Bay. If Hogg was around, they may have briefly talked with him – but they had to move on. As Olson noted, the day was cold and rainy -- so it would be a long, wet row to Fox Island – at least 3 hours, which meant they arrived at mid-afternoon.

“So we settled on Fox Island,” Rockie recalled. “I don’t remember the moving in detail, except for the enormous loads our venerable dory carried with gunwales a few inches from the water, chugging slowly toward the island. The sea was placid and the sky spectacularly bright.” Rockie recalled making “several preliminary visits” to Fox Island in preparation, going back and forth over a few days in the dory with its “second-hand, small cantankerous outboard motor.” Upon each arrival, “Mr. Olson met us with great excitement, helping unload the dory and pack away supplies, stacking them on the shelves, pushing boxes and cans under the table, behind the stove and high in the corners. Some were even suspended in the rafters. They lived in the Swede’s small house of milled lumber for a few days until they could at least clean out the dirty goat shed that would be their home.

In later years Kent marveled at how he was able to stow all his outfit into that small boat for the move to Fox Island. Rockie wrote that some of the lumber and hardware was delivered to them, probably sent by T.W. Hawkins. At some point Kent had approached T.W. about staying the winter with Olson. If you can put up with the old Swede and he agrees, it’s okay with me, Hawkins told him – this according to his daughter Virginia Darling. T.W. was insistent about Olson’s permission. Kent assured him that Olson had invited them to stay, and brought up the unused goat shed. I’m a good carpenter, he told the businessman. If I had the materials, I could turn that building into livable quarters and increase the value of your enterprise. My paintings could help bring the attention of Resurrection Bay and Seward to the outside world. It might help increase business and settlement. Hawkins agreed and supplied him with the tools and materials he would need.

Over a few trips carried a Yukon stove, an airtight heater, and stove pipe for both; pots, pans, bowls and other kitchen items; building material to upgrade the goat shed; a large trunk with books, a small suitcase, and a duffle bag and all “those prosaic necessary things,” Kent wrote years later. In Chapter II of Wilderness he calls them “the commonplaces of our daily lives,” and later in the book he catalogs his expenses. Kent brought his paints, but he had to buy turpentine and linseed oil. It annoyed him that his canvasses hadn’t arrived. He had expected them at Yakutat. Now Kent hoped they would arrive soon on one of Seward’s steamship arrivals. Rocky watched as his father carefully examined their cabin, made measurements, and “calculated the material requirements for the cabin’s salvation and alteration.”

During this trips to Seward, Kent most likely heard the grumbling about the growth of Anchorage and the coal issue. “One’s indignation fires at the recital of the men of Seward’s wrongs,” he wrote in Wilderness, “until you recollect that Seward was built for speculation, not for industry, and that by the chance turn of the wheel many have merely reaped loss instead of profit.” Before the tent city of Anchorage along Ship Creek sprung up in 1914, Seward had been the economic power in the area. It was still the railroad’s terminus, but in 1917 lost status as construction headquarters to Anchorage. From the beginning the goal had been to push the rails toward the coal fields north of Ship Creek.

As the U.S. Navy became more active in the Pacific fueling their ships became a serious issue, especially under the Taft administration. Most vessels still used coal which had to be shipped either from England or the eastern states. West Coast coal wasn’t high enough quality. To make matters worse, the Navy was forced to use foreign companies to transport the coal to the Pacific because American businesses hadn’t submitted bids and Navy colliers couldn’t handle the job. By 1910, it was estimated the battle fleet would need 200,000 to 250,000 tons of coal a month, and the Navy wanted to build coal plants at Puget Sound, Pearl Harbor, Panama, Corregidor, and along San Francisco Bay. Between 1912 and 1914 the Navy and the Department of Interior tested Alaska coal and found samples from the Matanuska fields suitable. Alaska became a territory in 1912, and this search for coal had much to do with the government’s willingness to both fund the construction the Alaska Railroad and then operate it. Never before had the government taken over operation of a railroad in the U.S. As William Reynolds Braisted notes in The United States Navy in the Pacific 1909-1922 (2008), in 1920 the government spent a million dollars to open a mine at Chikaloon at Matanuska, but the coal was not quality and expensive to transport and they withdrew two years later. By 1924 the Navy had begun its switch to oil and reduced its coal use significantly. In addition to the war, this was the Alaska political and economic context that Kent confronted in Seward.

Not long before Kent came to Seward, the tracks only extended seventy-one miles and were not connected to Anchorage. Seward wanted that section completed immediately so the coal could be shipped to Resurrection Bay – a deep, ice free port. The AEC’s priority had been to complete the tracks from Anchorage to the coal fields and have it shipped out of Anchorage – a port along heavily-silted Cook Inlet with extremely high tides that had to be frequently dredged. Cook Inlet also froze up in winter. By the end of 1917 a total of 121 miles could be used, but Seward was still not online. On October 24, 1917 the first train from Anchorage reached 73 miles north to the Chickaloon coal fields. Six days later the first coal shipment reached Anchorage. This was a significant achievement, but that coal would now be shipped out of Anchorage. By the first week of October 1918, the first freight and passenger service began between Seward and Anchorage. Although in 1918 Seward had no inkling that Anchorage would grow to the size it is today. Although the two towns had many social, political, and economic ties at this time, the coal, railroad and port debate became ugly and their two newspapers led the battle. Kent may have learned some of this information during the time he traveled back and forth between Seward and Fox Island supplying himself for the winter.

For Rockie those excursions to Seward could be unpleasant. “On several occasions on the Main Street,” Rockie recalled, “I was accosted by two or three boys and asked to explain my right to be in Seward. They were probably a few years older than me, but no bigger.” It was obvious to the 8-year-old that they wanted to start a fight, but he wasn’t interested. One of my sources and a good friend, Patricia Ray (later Pat Williams), was about eight-years-old at the time. She remembered the Kents and told me that the ritual Rocky faced was typical for new boys in town. The youngsters usually became friends later and Rocky says he was gradually accepted by the local boys. He had been schooled at home and had to maneuver his way through these kinds of different social interactions. He may have even unknowingly instigated these first encounters. He admits that the friendships got off to a shaky start because “I had made the mistake of bragging that I could count to ten in German.” Before 1914, that statement may have impressed the boys -- but after April 1917 and by August 1918, it caused suspicion. “When once accepted, though,” he wrote, “I joined them in games and, with time, explored the brooks and nearby woods.” But those initial challenges did cause problems. “I didn’t like to fight,” he wrote, “I didn’t know how to fight, and I was frightened.” When he told his father about this he got a “sermon on manliness, followed by boxing lessons.” Rockwell knew his son’s tendencies, and one reason he took him to Alaska was to toughen him up, perhaps to remove him from the female household of his mother and three sisters. In Wilderness, we see Kent wrestling and rough-housing with Rockie to help him lose his fear of physical confrontations. The lectures and lessons never took, he recalled later in life. “I never did become a respectable boxer. I learned that my hose was very sensitive.”

It’s December 1998. I’m sitting at Borders Books in Anchorage, signing copies of my Alaska books as well as the two Kent books for which I’ve written forewords – Wilderness and Northern Christmas. I’m hoping readers will see Kent’s Christmas book as an especially relevant gift.

Unless a writer is a Stephen King or a James Paterson, book signings can often go slowly. To pass the time I read an old, small and battered volume I picked up the day before in an antique shop – The Life and Travels of Pioneer Woman in Alaska by Emily Craig Romig. It’s a fascinating first-person account of her trip with her first husband from Chicago to the Klondike Gold Rush along the Canadian route. That was not the usual route stampeders took. It took Romig and her husband two years.

While I was reading a woman approached me – Rosemary Hanson Redmond, I later learned – and handed me a first edition of Kent’s “Northern Christmas,” a small book published in 1940 containing the Christmas chapter from “Wilderness”. “I thought you might want to see this. Read the inscription,” she said as I thumbed through it. As I read the handwritten dedication, I recalled Rockie’s memories of his Seward confrontation with other boys.

Dated April 13, 1976, it was written by Dr. Howard G. Romig, who was born in Seward on January 1, 1911. I had known Howard and taught some of his children in school. Howard’s father, Dr. Joseph Romig, was Alaska’s famous “Dog-Team Doctor.” The family lived in Seward for many years before moving to Anchorage. Howard eventually became a doctor and for a time practiced with his father. After his first wife died, Howard’s fathers, Dr. Joseph Romig married Emily Craig who had recently lost her husband. She was the Emily Craig Romig whose boo I had been reading. Synchronicity strikes again.

The inscription reads:

"To Rosemary Hanson Redmond with affection

Howard

I consider this little book a jewel -- I lived in Seward on Resurrection Bay Alaska at the same time the Kents lived on Fox Island. This brings back scenes of my childhood --and what is sad -- another scene of a frightened but, brave boy of 8 or 9 back up to the front of the Sexton Hotel. He was being tormented by some larger boys as being “Pro-German.” In response to the question “Do you like the Germans” -- he bravely responded “I’ve been taught to like all people.” It seems true that Rockwell Kent Sr. made an arrangement with Axel Lundblad -- (who ran a fish market) to let him know by a “light” or message when the frightful war was over -- and from this & other things the father & boy were considered sort of enemies.

I’d like to point out that my dad, Joseph Herman Romig 1 sent my childhood tutor and companion, Karl Von Brinkman Hall to Nashaqak for the duration of the war to escape a similar criticism -- actually to Mr. Mittendorf who

with my dad once ran a trading post. Later Mr. Hall emerged owner of the post, married a native woman and had a family. -- HGR"

PHOTOS

“Sailors from the U.S. Cruiser Maryland conduct a battalion drill up Seward’s Main Street in August 1912. You can see their vessel in port at the Alaska Railroad Dock in the distance. In April, while conducting practice maneuvers near Los Angeles, the ship was hit nine feet below the waterline by a torpedo. A ten-day repair in drydock was expected before it could proceed to San Diego. Later that summer it headed to Alaska. The vessel was a frequent visitor to Seward. The Maryland was in Alaska waters to investigate possible harbors for a naval base and coaling station. Seward was a prime candidate, and the town welcomed the vessel with open arms. While in town, the Maryland received orders to return to Bremerton, Washington to pick up Secretary of State Philander C. Knox and proceed to Japan for the funeral of Mutsuhito, the 121st Emperor of Japan who had died in late July. (Sylvia Sexton photo from the Michael and Carolyn Nore collection and published with their permission).

Bob, Jr. and Alice Hunt preparing to leave Seward with me in early August last year on a trip to Fox Island. They have a cabin on Fox Island, and the ruins of the Kent cabin sits on their land. Capra photo.

On that trip with the Hunts last year the fog and rain soon enveloped us and this is the view from inside as we approached Kent cove on Fox Island. Imagine rowing in Resurrection Bay in an 18-foot dory stuffed with supplies – “gunwales a few inches from the water” -- in weather similar to this.

Kent took this photo of Rockie (far right) with other children, probably while they were on board either the Admiral Schley or the Admiral Farragut. Rockwell Kent Gallery.

The arrow points to young Harold Romig marching with a children’s militia along Seward’s Main Street, circa 1918. He always remembered Kent’s visit to Seward, and especially young Rockie. Photo courtesy of Dr. Howard Romig’s daughter, Kerry Romig.

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

Aug. 29, 2018

“Wed. 28th. – Drisly rain and cold,” Olson wrote in his August 1918 diary. “Mr. Kint and is son arrived from seward this afternoon. goats out all night.”

“Thurs. 29th. – goats cam ome – 12:30 P.M. Mr. Kint Working on the Cabbin fixing at up. Drisly rain all night and all day.”

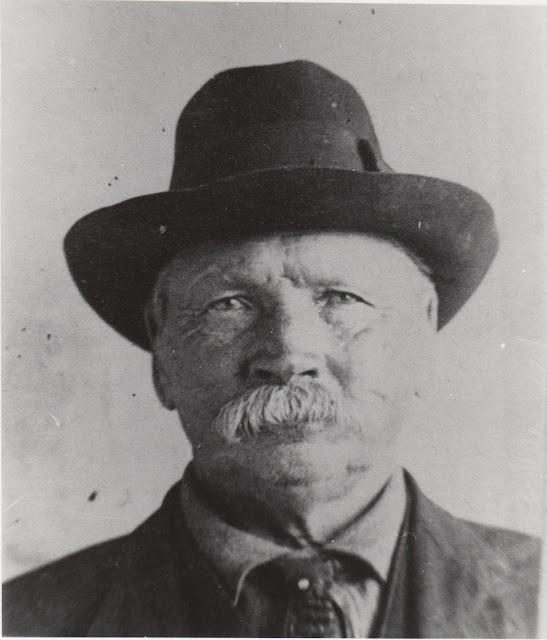

Lars Matt Olson

No doubt Olson was restless Wednesday, Aug. 28th, as he gazed off and on out to sea waiting for the Kents to arrive in their dory. The trip would take the artist and his son longer than they had planned. After their engine conked out, they dropped it off at George Hogg’s camp along the western shore of Resurrection Bay. If Hogg was around, they may have briefly talked with him – but they had to move on. As Olson noted, the day was cold and rainy -- so it would be a long, wet row to Fox Island – at least 3 hours, which meant they arrived at mid-afternoon.

“So we settled on Fox Island,” Rockie recalled. “I don’t remember the moving in detail, except for the enormous loads our venerable dory carried with gunwales a few inches from the water, chugging slowly toward the island. The sea was placid and the sky spectacularly bright.” Rockie recalled making “several preliminary visits” to Fox Island in preparation, going back and forth over a few days in the dory with its “second-hand, small cantankerous outboard motor.” Upon each arrival, “Mr. Olson met us with great excitement, helping unload the dory and pack away supplies, stacking them on the shelves, pushing boxes and cans under the table, behind the stove and high in the corners. Some were even suspended in the rafters. They lived in the Swede’s small house of milled lumber for a few days until they could at least clean out the dirty goat shed that would be their home.

In later years Kent marveled at how he was able to stow all his outfit into that small boat for the move to Fox Island. Rockie wrote that some of the lumber and hardware was delivered to them, probably sent by T.W. Hawkins. At some point Kent had approached T.W. about staying the winter with Olson. If you can put up with the old Swede and he agrees, it’s okay with me, Hawkins told him – this according to his daughter Virginia Darling. T.W. was insistent about Olson’s permission. Kent assured him that Olson had invited them to stay, and brought up the unused goat shed. I’m a good carpenter, he told the businessman. If I had the materials, I could turn that building into livable quarters and increase the value of your enterprise. My paintings could help bring the attention of Resurrection Bay and Seward to the outside world. It might help increase business and settlement. Hawkins agreed and supplied him with the tools and materials he would need.

Over a few trips carried a Yukon stove, an airtight heater, and stove pipe for both; pots, pans, bowls and other kitchen items; building material to upgrade the goat shed; a large trunk with books, a small suitcase, and a duffle bag and all “those prosaic necessary things,” Kent wrote years later. In Chapter II of Wilderness he calls them “the commonplaces of our daily lives,” and later in the book he catalogs his expenses. Kent brought his paints, but he had to buy turpentine and linseed oil. It annoyed him that his canvasses hadn’t arrived. He had expected them at Yakutat. Now Kent hoped they would arrive soon on one of Seward’s steamship arrivals. Rocky watched as his father carefully examined their cabin, made measurements, and “calculated the material requirements for the cabin’s salvation and alteration.”

During this trips to Seward, Kent most likely heard the grumbling about the growth of Anchorage and the coal issue. “One’s indignation fires at the recital of the men of Seward’s wrongs,” he wrote in Wilderness, “until you recollect that Seward was built for speculation, not for industry, and that by the chance turn of the wheel many have merely reaped loss instead of profit.” Before the tent city of Anchorage along Ship Creek sprung up in 1914, Seward had been the economic power in the area. It was still the railroad’s terminus, but in 1917 lost status as construction headquarters to Anchorage. From the beginning the goal had been to push the rails toward the coal fields north of Ship Creek.

As the U.S. Navy became more active in the Pacific fueling their ships became a serious issue, especially under the Taft administration. Most vessels still used coal which had to be shipped either from England or the eastern states. West Coast coal wasn’t high enough quality. To make matters worse, the Navy was forced to use foreign companies to transport the coal to the Pacific because American businesses hadn’t submitted bids and Navy colliers couldn’t handle the job. By 1910, it was estimated the battle fleet would need 200,000 to 250,000 tons of coal a month, and the Navy wanted to build coal plants at Puget Sound, Pearl Harbor, Panama, Corregidor, and along San Francisco Bay. Between 1912 and 1914 the Navy and the Department of Interior tested Alaska coal and found samples from the Matanuska fields suitable. Alaska became a territory in 1912, and this search for coal had much to do with the government’s willingness to both fund the construction the Alaska Railroad and then operate it. Never before had the government taken over operation of a railroad in the U.S. As William Reynolds Braisted notes in The United States Navy in the Pacific 1909-1922 (2008), in 1920 the government spent a million dollars to open a mine at Chikaloon at Matanuska, but the coal was not quality and expensive to transport and they withdrew two years later. By 1924 the Navy had begun its switch to oil and reduced its coal use significantly. In addition to the war, this was the Alaska political and economic context that Kent confronted in Seward.

Not long before Kent came to Seward, the tracks only extended seventy-one miles and were not connected to Anchorage. Seward wanted that section completed immediately so the coal could be shipped to Resurrection Bay – a deep, ice free port. The AEC’s priority had been to complete the tracks from Anchorage to the coal fields and have it shipped out of Anchorage – a port along heavily-silted Cook Inlet with extremely high tides that had to be frequently dredged. Cook Inlet also froze up in winter. By the end of 1917 a total of 121 miles could be used, but Seward was still not online. On October 24, 1917 the first train from Anchorage reached 73 miles north to the Chickaloon coal fields. Six days later the first coal shipment reached Anchorage. This was a significant achievement, but that coal would now be shipped out of Anchorage. By the first week of October 1918, the first freight and passenger service began between Seward and Anchorage. Although in 1918 Seward had no inkling that Anchorage would grow to the size it is today. Although the two towns had many social, political, and economic ties at this time, the coal, railroad and port debate became ugly and their two newspapers led the battle. Kent may have learned some of this information during the time he traveled back and forth between Seward and Fox Island supplying himself for the winter.

For Rockie those excursions to Seward could be unpleasant. “On several occasions on the Main Street,” Rockie recalled, “I was accosted by two or three boys and asked to explain my right to be in Seward. They were probably a few years older than me, but no bigger.” It was obvious to the 8-year-old that they wanted to start a fight, but he wasn’t interested. One of my sources and a good friend, Patricia Ray (later Pat Williams), was about eight-years-old at the time. She remembered the Kents and told me that the ritual Rocky faced was typical for new boys in town. The youngsters usually became friends later and Rocky says he was gradually accepted by the local boys. He had been schooled at home and had to maneuver his way through these kinds of different social interactions. He may have even unknowingly instigated these first encounters. He admits that the friendships got off to a shaky start because “I had made the mistake of bragging that I could count to ten in German.” Before 1914, that statement may have impressed the boys -- but after April 1917 and by August 1918, it caused suspicion. “When once accepted, though,” he wrote, “I joined them in games and, with time, explored the brooks and nearby woods.” But those initial challenges did cause problems. “I didn’t like to fight,” he wrote, “I didn’t know how to fight, and I was frightened.” When he told his father about this he got a “sermon on manliness, followed by boxing lessons.” Rockwell knew his son’s tendencies, and one reason he took him to Alaska was to toughen him up, perhaps to remove him from the female household of his mother and three sisters. In Wilderness, we see Kent wrestling and rough-housing with Rockie to help him lose his fear of physical confrontations. The lectures and lessons never took, he recalled later in life. “I never did become a respectable boxer. I learned that my hose was very sensitive.”

It’s December 1998. I’m sitting at Borders Books in Anchorage, signing copies of my Alaska books as well as the two Kent books for which I’ve written forewords – Wilderness and Northern Christmas. I’m hoping readers will see Kent’s Christmas book as an especially relevant gift.

Unless a writer is a Stephen King or a James Paterson, book signings can often go slowly. To pass the time I read an old, small and battered volume I picked up the day before in an antique shop – The Life and Travels of Pioneer Woman in Alaska by Emily Craig Romig. It’s a fascinating first-person account of her trip with her first husband from Chicago to the Klondike Gold Rush along the Canadian route. That was not the usual route stampeders took. It took Romig and her husband two years.

While I was reading a woman approached me – Rosemary Hanson Redmond, I later learned – and handed me a first edition of Kent’s “Northern Christmas,” a small book published in 1940 containing the Christmas chapter from “Wilderness”. “I thought you might want to see this. Read the inscription,” she said as I thumbed through it. As I read the handwritten dedication, I recalled Rockie’s memories of his Seward confrontation with other boys.

Dated April 13, 1976, it was written by Dr. Howard G. Romig, who was born in Seward on January 1, 1911. I had known Howard and taught some of his children in school. Howard’s father, Dr. Joseph Romig, was Alaska’s famous “Dog-Team Doctor.” The family lived in Seward for many years before moving to Anchorage. Howard eventually became a doctor and for a time practiced with his father. After his first wife died, Howard’s fathers, Dr. Joseph Romig married Emily Craig who had recently lost her husband. She was the Emily Craig Romig whose boo I had been reading. Synchronicity strikes again.

The inscription reads:

"To Rosemary Hanson Redmond with affection

Howard

I consider this little book a jewel -- I lived in Seward on Resurrection Bay Alaska at the same time the Kents lived on Fox Island. This brings back scenes of my childhood --and what is sad -- another scene of a frightened but, brave boy of 8 or 9 back up to the front of the Sexton Hotel. He was being tormented by some larger boys as being “Pro-German.” In response to the question “Do you like the Germans” -- he bravely responded “I’ve been taught to like all people.” It seems true that Rockwell Kent Sr. made an arrangement with Axel Lundblad -- (who ran a fish market) to let him know by a “light” or message when the frightful war was over -- and from this & other things the father & boy were considered sort of enemies.

I’d like to point out that my dad, Joseph Herman Romig 1 sent my childhood tutor and companion, Karl Von Brinkman Hall to Nashaqak for the duration of the war to escape a similar criticism -- actually to Mr. Mittendorf who

with my dad once ran a trading post. Later Mr. Hall emerged owner of the post, married a native woman and had a family. -- HGR"

PHOTOS

Bob, Jr. and Alice Hunt preparing to leave Seward with me in early August last year on a trip to Fox Island. They have a cabin on Fox Island, and the ruins of the Kent cabin sits on their land. Capra photo.

On that trip with the Hunts last year the fog and rain soon enveloped us and this is the view from inside as we approached Kent cove on Fox Island. Imagine rowing in Resurrection Bay in an 18-foot dory stuffed with supplies – “gunwales a few inches from the water” -- in weather similar to this.

Kent took this photo of Rockie (far right) with other children, probably while they were on board either the Admiral Schley or the Admiral Farragut. Rockwell Kent Gallery.

The arrow points to young Harold Romig marching with a children’s militia along Seward’s Main Street, circa 1918. He always remembered Kent’s visit to Seward, and especially young Rockie. Photo courtesy of Dr. Howard Romig’s daughter, Kerry Romig.

Comments

Post a Comment