August 30-31, 2018

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

These days 100 years ago Kent and his son were in Seward off and on between gathering supplies and making the Fox Island cabin livable. “Father laid a floor, cut window openings, mounted windows and roof, which he shingled, built shelves, a table and a bunk,” Rockie recalled. “I would like to report that we did all these things, but I believe I was of little help. I may have held the end of a board when so requested, but I think I was sent off to explore the woods, to get out of the way of flying nails and hammer.”

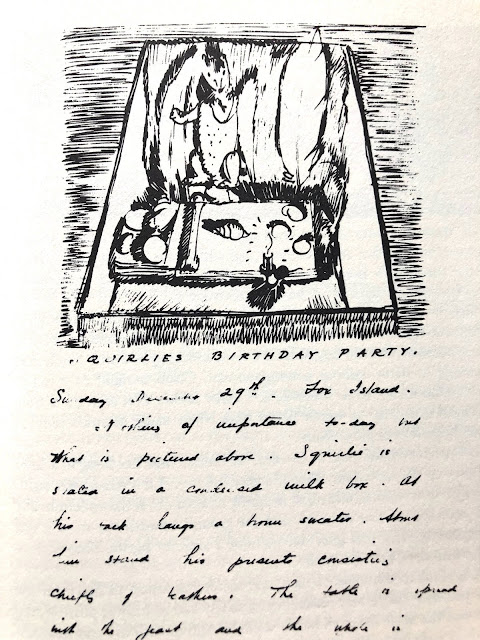

And what a place to explore for an eight-year-old! Kent mentions the flat, odd-shaped stones on the pebbly beach but only a few times. I’ve always been surprised that he never commented on the flat, heart-shaped stones we sometimes find. As I’ve strolled the beach over many years, I’ve finally come to understand why. Kent was not looking down – the artist was looking up – at the sky, the mountains and the sea. Not that he didn’t see the delightful assemblage of objects. It’s that he wasn’t focused on the ground. Not so with Rockie, I’m convinced. The day he celebrated his Squirlie’s birthday – that was his stuffed animal’s name – Rockie surrounded him in a little box with all the treasures he had collected on the beach. The beach and the woods became Rockie’s fairy-land where he created a world with animal friends with bizarre names.

The two didn’t spend too many days in Olson’s cabin. Kent worked quickly. “I marveled then and still marvel at the great energy with which Father tackled that project,” Rockie reflected, “and, for that matter, every project or undertaking, for as long as I knew him, whether it was writing a letter, building a house, engraving in wood, entertaining friends or defending a union. I prayed some of it would rub off on me!” That was Rockwell Kent, burning the candle at both ends with vitality that could exhaust those around him. His friend, Louis Untermeyer, once said “He’s not one person at all, but possibly the Rockwell Kent Joint and Associated Enterprises, Inc. Critic and playwright Lawrence Stallings, wrote: “Rockwell Kent was created partly to give the world arresting art, partly to write brilliantly of his adventurous life, but chiefly to demonstrate, that nature did not, after Leonardo Da Vinci, forget how to produce a man who could do everything superbly.”

Kent was not only busy on the island but also in town. On this day 100 years ago, he posted a letter to his friend Carl Zigrosser in New York: “I’ll write soon,” he promised. “Have found a regular Robinson Crusoe island with a snug log cabin to live in. Today R and I start for there; it is 12 miles down the harbor. I wish you were here to enjoy it all with me. Seward is a glorious place – all but the town itself. That’s typical of all Alaska that I’ve seen, utterly common. There are good friendly people here.” Kent included a post card photo of birds on the sea and another of Bear Glacier taken by his new friend, John E. Thwaites. “This glacier is only a short distance from my island,” he wrote. “I’ll send you a copy of the chart of this bay so you may clearly see the {area}and think of us often.”

Early on Kent saw the Seward Chamber of Commerce ad in the newspaper gloriously acclaiming the frontier town on Resurrection Bay as the “New York of the Pacific.” The presumptuous title came from a series of articles published in 1916 by travel writer Frank G. Carpenter who had visited Alaska the year before. What a contrast Kent noted between their life on Fox Island and “this roseate vision of the little city on the far northwest!” Kent wonders at Seward’s infrastructure – a hospital, grammar school, churches, a French barber from the Hotel Buckingham, a Baker from Wards Bakery in New York. Apparently, Kent assumed Seward didn’t miss the fact that they had no library – implying the lack intellectual stimulation. In fact, Seward had several circulating libraries and the town thrived on lectures, debates and musical events. Later, as Kent got to know some of its people, he changed his mind.

On the one hand, the town had the evolving cosmopolitan character of a principal port. On the other hand, Kent saw it as a typical Alaska town and commercial outpost. “Seward’s a tradesmen’s town and tradesmen’s views prevail,” he wrote, “narrow reactionary thought on modern issues.” During one December visit from Fox Island, he laughed because the Seward Gateway editor over reacted to a strike by his newsboys, considering it a I.W.W plot. If he had read the event more closely, he would have noticed that most of the town also saw the humor. Days before he left Alaska, Kent would have a confrontation with this editor and with a newly-hired school teacher. But for now, Kent just wanted to get out of town and settle on Fox Island.

Kent also learned how the Great War had affected Alaska’s economy. When the war began in August 1914, plans were underway to begin construction of a Government Railroad from Seward to Fairbanks. Many miners in the territory were from Canada, and quit their jobs to join the military. With the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 followed by increased German unrestricted submarine warfare, the U.S. got closer to war. More American citizens began to join Canadian, British, or Red Cross forces. Interior mining towns were hit hard. The population of Alaska decreased. Then, in early 1917 came the Zimmerman Telegram – with Germany trying to convince Mexico to attack the U.S. in return for land they had lost after the Mexican War.

After the U.S. declared war in April 1917, many railroad workers, along with other Alaskans, were either drafted or volunteered – nearly 16,000. The pressure to either volunteer or register was extreme. Those who didn’t were called “slackers,” and arrested. Some Alaskans left the territory for better paying jobs in the states. In November 1917, the Alaska Engineering Commission (AEC), responsible for railroad construction, had 2,798 on its payroll. By March 1918, the number had dropped to 1,084. Progress slowed and business that had depended upon these workers suffered. The 1910 census recorded Alaska’s population as 64,000. By the 1920 census it had declined to 55,000. The last Alaska gold rush, the Iditarod, had ended, but most of the population decline was due to the war. Churches lacked ministers and priests. Ads ran in local newspapers urging people not to leave Alaska. Many Alaska dogs were drafted into war service. Before the railroad was complete and airplane travel became common, dog teams were integral in transporting people and all kinds of supplies. Lack of dogs for this work had its impact on the local economy.

In 1915, one mile of track cost $9,860 to build. By 1918, the cost had risen to $14,691. ARR construction expenses went over budget. Back in 1914, Congress had allowed $35 million for the entire enterprise. That was gone by June 1919. Congress granted an additional $17 million, but it would be paid in three installments in 1919, 1920 and 1921. Workers sometimes had to wait months to be paid. When completed in July 1923, the Alaska Railroad had cost over $70 million.

While all this was happening, the influenza epidemic killed at least 750 Alaskans.

This background explains why at first Hawkins was concerned about Kent staying on Fox Island. He didn’t want to get on the bad side of Olson. These days it was difficult finding a caretaker for such an enterprise, and the war had brought much uncertainty to the fur trade. In The Fur Farms of Alaska: Two Centuries of History and a Forgotten Stampede (2012, Sarah Crawford Isto writes: “Many island caretakers and young fur farmers in the territory joined other Alaskans in leaving for the military or for high-paying shipyard work in the States. Twelve percent of Alaska’s white population, which was largely male, entered either the army or the navy. For fur farmers who remained in Alaska, the good news was that demand was high, and American fur auctions were rapidly expanding to replace London. The bad news was that many furriers had been trapped on the opposite side of the Atlantic by war. The passage of furs from farmer to consumer was slowed in the garment workshops. Moreover, times were uncertain. No one knew when the war would end or what the world would look like when it did.”

NOTE – In addition to the letters, I’ve listed my more important sources throughout these entries. Here are a few others I’ve used: Philip Blom’s two books, The Vertigo Years: Europe 1900-1914 and Fracture: Life & Culture in the West, 1918-1938; Mark Sullivan’s five-volume history of the years 1900-1920 titled Our Times; Preston Jones, The Fires of Patriotism: Alaskans in the Days of the First World War 1910-1920; Kevin C. Murphy’s unpublished PhD. Dissertation from Columbia University (2013) is particularly valuable. It’s titled Uphill All the Way: The Fortunes of Progressivism, 1919-1929 and is available on line.

Photos

1. Some of the treasures Rocky would have found while walking the beach in front of the fox farm – varieties of kelp, feathers, fish bones, worn cottonwood bark, and jellies. Capra photos.

2. Every six hours we go from high to low tide in Alaska. At the north end of the fox farm cove Rockie found a perfect place to explore at low tide. Capra photos.

3. Although Kent doesn’t write much about the beach and intertidal zone, it’s clear that Rockie explored it and collected birthday presents for his stuffed animal, Squirlie. This illustrated letter is from the Wesleyan University Press edition of Wilderness.

4. In 1915 internationally-known travel writer Frank Carpenter traveled to Alaska to write a series on Alaska. The next year his columns were syndicated in newspapers across the country. This is the article he did about Seward as it appeared in one specific newspaper.

5. The entire area Lars Olson attempted to homestead on Fox Island and the specific area of the fox farm. In the left-hand photo – about and to the right of Fox Island is Humpy Cove; above and to the left of Fox Island is Caines Head. Photo courtesy of Mark Luttrell.

Comments

Post a Comment