OCTOBER 14 - 17, 2018

ROCKWELL

KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100

YEARS LATER

by Doug

Capra © 2018

Early to Mid-Oct., 2018 – Part 2

(Unless otherwise noted, all Kent letter quotes and images are from the online Archives of American Art Rockwell Kent Papers. Quotes from Carl Zigrosser's letters are courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania.)

(Unless otherwise noted, all Kent letter quotes and images are from the online Archives of American Art Rockwell Kent Papers. Quotes from Carl Zigrosser's letters are courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania.)

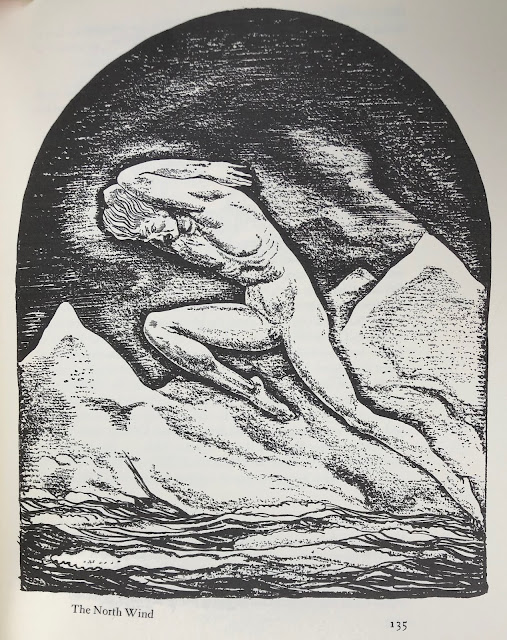

As we look back to Fox Island 100 years ago – Oct. 13, 1918 –

we find Kent and Rockie packed and ready to venture to Seward. The rain has

stopped and Kent calls it a “wonderfully beautiful day” but “with a ranging

northwest wind.” Power, strength, force, youth, vitality, energy – life itself –

that northwest wind. Although it prevented him from heading to Seward – perhaps

because it had the authority to do so – Kent admired its audacity. “I must sometime

honor the northwest wind in a great picture,” he wrote, “as the embodiment of

clean, strong, exuberant life, the joy of every young thing, bearing energy on

its wing and the will to triumph.” The will to power – right out of Nietzsche. It

reminded him of Monhegan Island on such days when an artist would creep from

his hole and groan “How can one paint?...such sharpness!” The harsh severity embodied

no mystery so the artist, “this fog lover…crept back…to wait for earth’s sick

spell to return.” But Kent did paint that day on Fox Island.

Rockie helped his father clear land, trim trees and cut

firewood, but spent much time wandering the woods. The goats too wandered

freely, and the youngster thrilled in finding their wool stuck on tree bark and

brush. He followed porcupines, observed river otters, and walked the beach collecting

treasures for himself and his stuffed animal, Squirlie. The resident Orca pods

sometimes rubbed their bellies along the shore, and Rockie recalled them so

close one day that he could touch their dorsal fins with his walking stick.

At Kent’s

guiding he practiced his writing, longing to someday record his dreams. The last

few mornings the artist and his son had heard Olson testing his motor. Kent’s

engine was in repair – probably at Hogg’s camp between Caines Head and Seward –

so Olson would give them a tow to Caines Head. Meanwhile, the pet magpie sang

in its cage, or at least made “strange glad noises in his throat.” Members of

the Corvid family and related to Steller’s Jays, magpies are among the most

intelligent of animals. A caged life would have been a conscious torture for

the bird – ironic that Kent would confine wildness with all his espousing of its

freedom and liberty. The prisoner in the cabin wall cage would not have a happy

end.

In this photo, a "parliament" of Black-Billed Magpies gather around one of their dead while another Magpie observes. Magpies feel grief and even hold funeral-type gatherings for their fallen friends and lay grass wreaths beside their bodies, some animal exerts claim. (Capra photo)

On Oct. 14, 1918 the weather cleared enough for Olson to tow

them to Caines Head. “From there we made good time,” Kent wrote, “Rockwell

rowing like a seasoned oarsman, as indeed he has now a right to be called.” They

picked up their engine along with a gift of turnips and six lettuce heads grown

there. In town Kent picked up his letters at the post office, always the main

reason for venturing to Seward. He noted that the snow which had gradually been

covering the mountains had reached town. That evening, as a storm raged

outside, the two enjoyed an evening with post master William E. Root and his

family. Root first came to Alaska at Skagway in 1900. In 1916 he became

postmaster at Seward. Before his appointment he was a druggist in Cordova. His

daughter, Florence, was a talented musician who played professionally and

traveled to other Alaskan towns. She also played theater organ for silent films

and taught school in Seward and Metlakatla, near Ketchikan. That evening in

Seward Kent played his flute to Florence’s piano accompaniment – Beethoven,

Bach, Hayden, Gluck, and Tchaikovsky. As the evening wore on, Rockie tried to

keep awake by feasting on milk and apricot pie. As they left, the Roots gave

them a gift of wild currant preserve. The storm raged while Kent read his

letters probably at the Sexton Hotel – but later as he made more friends, he

would be offered free housing on his trips to Seward. This evening, though, he

worried about his boat along the shore. He decided to check on it and found it

safe but too low down so he hauled it up beyond the high tide range. On this

day, Oct. 14, 1918, Kathleen sent two important notarized documents to Kent

that he had asked her to obtain. The

first attested to their marriage. The second in Kathleen’s handwriting attested

to her being his wife and listed their children. Their child that would later

be named Barbara is here named Hildegarde. Kent needed these documents to show

the local draft board to get a deferment. He wouldn’t get these documents for

at least a week or two.

The next day – Oct. 15, 1918 -- Kent registered for the

draft in Seward. He most likely did this with much guilt -- for he opposed he

war and the draft – but he had to register if he were to remain in Alaska.

Thousands of American soldiers were dying at that moment in France as the final

battle of the Great War – the Meuse-Argonne – raged on. Historians have called

it the bloodiest battle we ever fought. There would be no toleration in Seward

or anywhere else in the U.S. for “slackers” who refused military induction.

Kent’s close friend, Roderick Seidenberg had declared himself a conscientious

objector and refused to register. He was imprisoned in a dark cell, fed on bread

and water, and tortured. On Feb. 17, 1919, the day Kent decided to soon end his

stay on Fox Island, he wrote to Carl Zigrosser, “But about Seidenberg! I raged!

It is almost beyond belief. The cowardly scoundrels with that tender young

idealist.” Through Zigrosser, Kent wrote a letter to Seidenberg: “It is only by

the slender thread of the endurance of such a man as you that any of us can now

believe that the spirit of what man shall become is stronger than the best of what

he has been…Your sufferings have finally embittered by hatred for such a

civilization as is in American today and of such a government and army as, in

the name of Liberty, become Tyrants.” Kent urged Zigrosser to publish a book

with him exposing Seidenberg’s agony. Both he and Zigrosser seethed not only of

their friend’s ill-treatment, but also at “the terrible state of the world,” as

Zigrosser wrote, “how the brutish greed and hypocrisy of those in power is equaled

only by the sheepishness of those who are not.” The sheep, Nietzsche’s herd –

those who follow thoughtlessly resulting in what Hannah Arendt would later call

“The Banality of Evil.” I’ll discuss this issue more when we get to February

1919, but for now I thought it necessary to connect it to Kent’s willingness to

register for the draft in Seward on Oct. 15, 1918. In his Wilderness journal, Kent simply writes on that day, “To-day it

rained incessantly. I have bought a few odd supplies and registered for the

draft.” Nothing else.

That night Kent and Rockie spent the night at the “house of

a young man whom we’ve found congenial and who above all is a friend of a young

German mechanic for whom I’ve a liking.” That mechanic was probably Otto Bohem

who worked for Jacob Graef who had invited Kent to the berry picking party and

sold him his boat and engine. The house was out of town “on the boarder of the

wilderness” and made of logs. Kent probably played his flute and the group sang

before an open fire. “There are spots like this little house and its hospitable

hearth,” Kent wrote, “that show even the commercial desert of Seward to have its

oases.”

On Oct. 16, 1918, Kent wrote letters to put on the outgoing

steamers, including one touching note with a poem to his daughter, Hildegarde.

Never knowing when the weather would allow his next

trip to Seward, he wandered town gathering supplies. “It poured rain and blew

from the southeast,” he wrote. That night he and Rockie spent time with his

German friends and arranged to signal back and forth, mostly to learn of the

war’s end. This was not a wise move. Not only did it put his German friends in

danger, it also helped spread a rumor in Seward that there was a German spy on

Fox Island.

The next day, Oct. 17, 1918, Kent and his son left Seward at

9:45 in the morning with a thousand pounds of supplies. The day began with calm

but as they crossed to the east side of the bay at Caines Head the north wind

rose. Fortunately, they had found the perfect weather window for their trip

home. “The little three-and-one-half horse-power motor worked splendidly,” Kent

wrote, “and carried us to the island in a little over two and a quarter hours.”

That was probably a record time for his trips. Back on Fox Island he learned

that the storm he had experienced in Seward had prevented three mariners from

making it out of Resurrection Bay. Two had left but the third remained on the

island and told Kent that this was the worst weather he had seen in twenty

years.

To their dismay, Kent and Rockie also found the magpie dead

on the floor of its cage. Apparently, Olson had forgotten to cover the cage as

requested and the storm had killed the bird. “Rockwell, who straight on landing

had run there, wept bitterly but finally found much consolation in giving him a

very decent burial and marking the spot with a wooden cross.”

Comments

Post a Comment