PART 2 OF 3 -- THE FINAL ALASKA LETTERS

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

April 9, 2019

Part 2 of 3 – The Final Alaska Letters

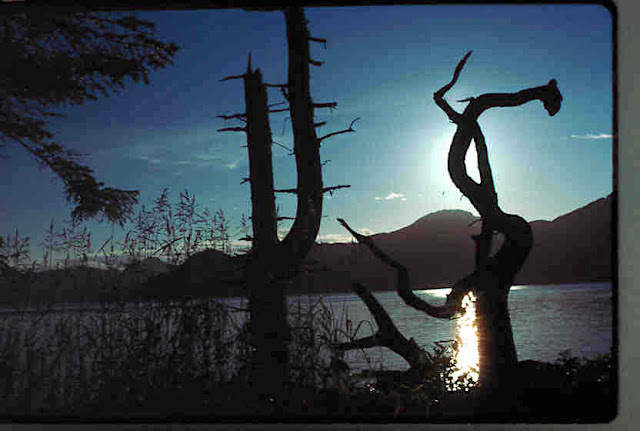

ABOVE – Fox Island Scene from the site of the Kent cabin ruins. I took this

photo back in 1996. Within a year or two the twisted snags had disappeared. It always

reminded me of Rockwell Kent’s painting below. The fierce north wind during

winter in Resurrection Bay whips up the salt spray which shapes and structures

the landscape, wears it down, and changes it radically year to year. Capra

photo. BELOW – Tierra del Fuego, Admiralty Gulf

1922-23 by Rockwell Kent.

On Feb. 25, 1919 Rockwell to

Kathleen: I love you ever ever so dearly

and you must be a very happy girl till I get home and need no one else to keep

you good. That “no one else” refers specifically to his friend, George

Chappell who has been looking out for Rockwell’s family, ironically at the

artist’s request. Indeed, the artist has asked George to look after his family

if something happens to him in Alaska, and his friend has graciously agreed.

But Kathleen’s deep friendship with him disturbs Rockwell. No one can replace

him in any way, Rockwell feels, and Kathleen has told him only George is able

to listen to her without misunderstanding. BELOW -- George Chappell.

Feb. 15, 1919 Kathleen to Rockwell:

I was dreading spending this evening alone

for the mood was still lurking in the background. Once again I and you…have

George to thank for bringing me away from blue and despondent thoughts. I very,

very often feel that nobody looks my way, and then George appears, and I

realize that I have, beside a dear husband who loves me madly a dear and true

friend who (would do anything) he could to make me happy. Yes, I am happy

tonight, in your great love and George’s wonderful friendship. Darling, I hope

we will have no more tragedy in our lives, we have had enough to last us for

always and always.

The whole issue of friendships emerges in these last Fox Island letters.

Rockwell has issues with some of Kathleen’s friends, especially Bernice and

Billy, and Elizabeth. They are spying on Hildegarde for her, providing

misinformation, he believes. They are also encouraging Kathleen to challenge

him, he is certain, instigating a breakup of their marriage. Rockwell expects

his friends to be her friends, Kathleen tells him – and, thus, she expects him

to respect her friendships.

Feb. 18, 1919 Kathleen to Rockwell: I wrote to George because (he is the) one

and only person I can unburden my soul to. I haven’t been able to locate

any of Rockwell’s or Kathleen’s letters to George Chappell. Perhaps they no

longer exist. Even though he trusts George, Rockwell cannot tolerate Kathleen’s

dependence upon him. The fact that George is the only person Kathleen can

unburden her soul to is completely unacceptable to Rockwell. And he doesn’t

know precisely what they’re talking about – although it must be about him. From

one of George’s letters to Rockwell, it appears that Kent is questioning his

friends loyalty. George responds with admiration for Kent and cautiously. As

Zigrosser has suggested, those who know Kent understand how sensitive he can be

to criticism. BELOW -- Kathleen as young wife.

Feb. 16, 1919 Rockwell to Kathleen: Is my love for you still of so little

account and yours for me so feeble that your virtue hangs on the friendship of

another man? After all that I have written, you tell me that still, if it were

not for George, you would become a {BLACKED OUT WORD}. Oh, God! What is

that blacked-out word? If I were to guess -- it might be “whore.” That sounds

harsh, but it must be something as unacceptable because Rockwell rarely blacks

out anything, even some very harsh criticisms. But, by this point he has

promised Kathleen that he will try to tone down his letters, i.e. not write

whatever pops into his head during despondent moment. This blackout is probably

his attempt to be more mindful of what he is saying.

Feb. 14, 1919 Rockwell to Kathleen: But this is my decision now. It is simply

impossible for me to leave you alone any longer. I shall paint now with all my

energy and try and get some good-sized sketches done and then leave for home…Understand

little wife that I have a very deep respect for your wisdom. Please be always

better than I am. I want something to worship. When I blame you it is not as a

woman but a rare heroine who “nods” a little once in a while. I know it’s

darned annoying to be worshipped but that’s your job and you must just make the

best of it.

Feb. 14, 1919 Rockwell to Kathleen: I see that you may misunderstand my response

to George in regard to your promise to me. He demanded she send her promise

to him in a telegram. His question: Will you be faithful to me always? The

answer he wanted was “Yes, always,” and Kathleen did send a telegram with those

words. I mean nothing wrong there. I know

that it is his friendship and good cheer that you mean have kept you straight;

but nevertheless I will not trust your soul to the friendship of another man.

If you had said that your love for me was too deep for you to think of, then I

would have been content. You realize, don’t you, the hideous danger that you

have told me hangs continually over your head?

ABOVE -- Typical rain and fog like what Kent experienced on Fox Island during his first two months there. This shot is taken from the ruins of the Kent cabin. Capra photo.

Feb. 15, 1919 Rockwell to Kathleen: I am scheming to return again sometime {to

Alaska}. Of course, if I do you’d have

to come too unless you’d consent to be locked up in jail…And in that letter of

New Year’s Eve you speak of the future, but not once of what you

will do for me or what you will bring into our life there in the

country. But of what you will “require” of me. I require many

things of you and things you have not given in the past. I want a strong,

brave, true wife with ideas that do not falter from day to day. I need comfort often and mothering and

sympathy. I can’t stand alone.

March 15, 1919 Kathleen to Rockwell. A month later, Kathleen responds to Rockwell's demands above: You have asked me months ago to tell you my dreams of our new life together, and you are peeved because I have not told you things that I am going to do for you. As in the past, I have given and done everything {for} you that I know how and it did not bring us happiness; this is what I {will do} in the future. I am going to have a little world of my own with which ___ I ___ only __ humbly and entirely at my will...You get disagreeable and make me unhappy; knowing that, you will be {awfully} careful, if you really {need me}. Does that please you? No, it doesn't, I know. You want me to be entirely yours, body and soul, and mind. But I'm not going to be, for that brings us only unhappiness. See how precious I am to you when you are away from me. You had too much of me and tired of me as we do anything we have too much of. That's enough on that subject. And now, sweetheart, here's a kiss goodnight, a thousand of them, and oceans of love, from your Kathleen. Kathleen has developed a voice and the courage to use it. Of course, it's one thing to talk to Rockwell like this from thousands of miles away. It's another thing to face his powerful persona face to face. But she's made a few things clear. She's willing to give their marriage another chance, but on terms that will satisfy her as well as him. We don't know for sure whether Kent got this letter before he left Alaska. He left on March 30th. The earliest he could have picked up the mail in Seward would have been on Friday, March 28th. Thirteen days could have been enough time for this letter to arrive. If it didn't arrive on time, he wouldn't have read it until its return perhaps two weeks after his return.

Feb. 16, 1919 Kathleen to Rockwell: Your next letter is more about my coming.

No, dear, I feel that it is better that I stay right here till you come back. I

have had many qualms that your great love and worship and need of me are merely

passion. Passion is a code word for sex. Let’s be up front and honest here.

Seward is a small railroad town, but it has a thriving red-light district. Rockwell

is rarely in Seward and not for very long periods. He’s befriended the locals

and has earned their respect. It’s most likely he’s been without sex during the

entire Alaska visit, and very unlikely he’s made a trip to Seward’s “Line.” That’s

not Kent’s style. Kathleen realizes his condition and is concerned with his “mere

passion.” On the same day while on Fox Island, Rockwell constructs the

narrative he wants Kathleen to accept for his return, the story she must tell

everyone. It will be somewhat hard to

explain this {Rockwell’s early return}

to our friends and I must ask you to let me tell the true cause. If I said that

I was tired of it or too homesick it would discredit me and make it hard to get

money for another venture at any time. For this money has been pretty much

wasted. I shall write to Dr. Wagner and to Carl and simply say that you are in

so despondent a mood that I cannot leave you alone and must come home. Don’t

mention my coming to anyone. I’m too ashamed of it. Please, dear, don’t put the blame for this on

me when you speak of it to others afterwards – unless you care at the same time

to tell them what you have written me and wired me. Please don’t misrepresent

my actions to Mother. Tell her simply that you have written me such blue

letters that it drove me to come back. We see his concern of his mother’s

opinion. Rockwell is ashamed, especially concerned that his mother get the

“correct” narrative for his return. He’s fearful the whole trip has been a

failure, the money wasted. Most of his important paintings are unfinished. In Wilderness, in the Feb. 17th entry, he

writes “It has become necessary to go

back to New York very soon. I told Rockwell of this to-day and his eyes have

scarcely been dry since. He gives no specific reason for his return. In It’s Me O Lord, his 1955 autobiography,

Kent writes: Kathleen, deaf to my pleas

that she join me – leaving the children, as she might have done, with her

mother and mine – and, seemingly, unconcerned at the swift drainage of our

resources which her unnecessary life in New York City was effecting, made it

increasingly evident that both to save our marriage and support the family I

must quite Alaska and go home. It’s all Kathleen’s fault. If you’ve been

following this website so far, and reading Kathleen’s letter excerpts, you see

how false is this narrative Rockwell has created. Indeed, Kathleen scrimps and

saves and feels guilty that she’s spending money Rockwell could use for his

Alaska trip. Kathleen is instrumental in getting Dr. Theodore Wagner as a

patron for $2000 to allow Rockwell to stay in Alaska over the summer. Kathleen

socializes with other connections in the art world like Marie and Albert

Sterner to help promote her husband’s career. She circulates his illustrated

journal, distributes his Chart of Resurrection Bay and other pen and inks. She is

instrumental in his achieving the success he finally does. I don’t know for certain,

but I would guess that Rockwell did not delve into all the personal letters

from his Alaska period in research for his autobiography. By 1955 the real

story was set in his mind. As Zigrosser has suggested, he obliterated that part

of his life. And why not? His early return didn’t matter. His fear had been

groundless. The Alaska venture had been a success. The end result had been his

fame.

BELOW -- Carl Zigrosser in 1970 leaving his Pine Street residence in Philadelphia. Photograph by Adrian Siegel, from Zigrosser's memoir, The World of Art and Museums (1975)

Rockie is devastated to learn they must

leave early. So is his father. He’ll have no trip to Bear Glacier, and no

excursion along the coast to see the fjords and paint that extraordinary land

and seascape. Kent’s been defeated, part of him feels. Not only by his inner

insecurities, but also by the wilderness itself – the weather, the seas, the

north wind, the isolation, the darkness. Zigrosser notes that after Kent’s house in

Upstate New York (Ausable Forks) burned in 1969 – Rockwell was 86 years old – “his immediate response was to rebuild it in

the same form and shape as it formerly had been…He wanted to blot out the

memory of the calamity and live as before…He had terrific will power and an

unshakable belief that he could accomplish anything that he decided to do. This

feeling of invincibility carried him successfully through most of his life.

Whatever he could not meet and overcome – he was very competitive – he would

obliterate and act as if it had never existed. Had he lost is faith, the whole

structure of his life would have crumbled.”

In 1919, Rockwell could not abide the

truth of what he considered his defeat in Alaska – the real reason for his

early return. This new narrative was his way of obliterating it. In It’s Me O Lord Kent briefly summarizes

the published Alaska story. Zigrosser wrote: “As with most autobiographies, it is in fact an apologia pro vita sua and contains the usual amount of inaccuracies,

half-truths, and evasions. In saying this I do not minimize the obvious merit

of the book. It is a marvelous projection of a personality and a record of a

full life lived on many levels. The book is

the man. But from the fulness of my knowledge I can not accept his legend

entirely at its face value, nor refrain from expressing my sympathy for some of

those who have experienced his disfavor.” There were subjects that even his

close friends dared not discuss with Rockwell. Zigrosser wrote: “It was not, however, Rockwell’s

temperament, when he had convictions, to refrain from expressing them forcibly

on all occasions. I found it expedient, therefore, to avoid, as far as

possible, arguments on certain issues, debates in which neither could convince

the other, and which could lead only to the aggravation of tempers for no good

reason.” This temperament most certainly applied to Rockwell’s narrative of

his personal life. Zigrosser had written a portrait of Rockwell in 1942 for The Artist in America. Kent loved it.

Zigrosser later revised it and read it to Rockwell in 1967. “He begged me so earnestly not to publish

the work that I had no choice but to comply. I did not promise never to publish

it, revised of course, but to postpone it until a later date, which might be

after his death. I was surprised by the vehemence of his solicitude.” This

work probably became the chapter in Zigrosser’s memoir, A World of Art and Museums, published in 1975 – four years after

Rockwell’s death. The Zigrosser quotes in this and the last entry come from

that book. Few people knew Kent as long and as well as Zigrosser. “When I was young,” Zigrosser wrote, “I admired him uncritically. As I grew older,

I saw him as a human being endowed with certain frailties that I was prepared

to accept. I felt, however, that to acquiesce invariable was dishonest: I had

my own opinions and was not just a yes-man. I viewed him now in perspective: my

regard was tempered but also deepened. I admired him with more understanding.

Such a new dimension in friendship was a more worthy tribute to him and to me

than uncritical admiration. Thus the bonds of our friendship were never

broken…” Zigrosser represents one of the best sources for understanding

Rockwell Kent’s complex personality.

BELOW -- Kathleen, with little Kathleen, Clara and Rockie at Brigus, Newfoundland in 1914. Photo from the Kent/Whiting family photograph album reproduced from Vital Passage: The Newfoundland Epic of Rockwell Kent with a Catalogue Raisonne of Kent's Newfoundland Works by Jake Milgram Wien (2014)

March 7, 1919 Kathleen to Kent: I am well excited about your coming back so

soon, we all are, but I suppose you have misunderstood my letters to expect my

thinking it unwise to leave me alone any longer. However, I will bear

the blame and if it gets too heavy for my shoulders, then not only in my

letters but our life together. This is the reason I think that my love for you

is not as (easy) as yours for me. It has suffered a relapse after the

struggles. Kathleen agrees to Rockwell’s narrative of why he’s returning

home early, even if the burden gets too heavy for her to bear. She will take

the blame. But she’s also clear in the letters that he has no reason to distrust

her fidelity to him, and that she can take care of herself. Consider – she’s

been alone with the children during much of their ten-year marriage. She’s

raised the kiddies pretty much on her own, looked after bills, cooked the meals

while doing the shopping, and working to promote Rockwell’s career. Kathleen

also makes it clear that asking her to accept conditions like this makes it

difficult for her to give him the love he wants.

The reader has to view RK in the context of his time, but in the contemporary currents of the, "me too" movement and other patriarchial reconsiderations of history, in this small reading, I could not stop thinking about the times we live in. What drove RK, his passions, art, decisions, etc.. The beginnings of an intriguing psychological profile is reflected above: RK's exceptional charm when he desires something, quick anger when he is thwarted; extraordinary willfulness to succeed where others generally fail; narcissistic defiance to accept one's own faults and quickness to blame others, without empathy for their own condition, thoughts or feelings. Who is RK, what psychologist's describe as, "the dark triad" or a brilliant misunderstood creative mind?

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comments. Excellent questions. In trying to answer those questions I use as my sources the letters and reflections from two people who knew Kent best during those years and later -- Carl Zigrosser and George Chappell. I've quoted from them on the website. I've also used the insights of other Kent scholars who have written articles and books -- esp. David Traxel, Jake Wien, Frederick Lewis, and many, many others that I don't have space to mention here. We do have letters from the Kent-Zigrosser correspondence, but they talk mostly about art and politics, with some descriptions of Kent's doings on Fox Island. In those days, though, Zigrosser admits he was a young admirer of Kent and not much of an objective observer. It's in his 1975 memoir, published after Kent's death, that we get a very revealing chapter about Kent. I've found only a few letters from Chappell to Kent but at least one of them is extremely revealing. I've not found any letters from Kent to Chappell but I've been able to construct what's going on from what Kent tells Kathleen about those letters -- and from what Kathleen tells Kent about George in her letters. Kathleen says she has written letters to George, too, but I've not located any of those. Essentially, George pleads with Kent not to let his excessive idealism, his unrealistic expectations of his wife and family, end up destroying his marriage. Chappell urges Kent to cherish the wonderful wife and family he has and learn not to criticize them so much. Appreciate them. He can still strive for the ideal, Chappell tells him, but don't let that quest ruin what beauty is already yours. That tells us a lot about Kent -- and you can see precisely what Chappell is talking about in Kent's letters to Kathleen. All this I've discussed on the website. What drove Kent, made him who is became? First, we must understand that Kent, born in 1882, was raised as a late-Victorian gentleman with all those values, customs, traditions, prejudices, and biases. That includes sex and his attitudes toward women. Combine that with the fact that his father died when he was five years old. He was raised by his mother -- who Zigrosser suggests throughout his life was the only one who wouldn't put up with his antics and wouldn't hesitate to argue with him. Kent was a difficult child to raise. He was also raised by his mother's aunt, and her sister -- both women named Josephine, thus two Aunt Josie's (confusing). His mother sister, an artist herself, probably was easier on Kent, as was his young Austrian nanny, Rosa. He probably grew up, as the oldest child (brother, Douglas and sister, Dorothy) admired, catered to, adored, and fussed over. Through his life he demanded, expected, craved, and insisted upon that from his women. Zigrosser tells us he wore out two of his wives. We can clearly see how he wore out Kathleen. I've read all the letters from their marriage in 1908 to the time he left Fox Island at the end of March 1919 -- and most of the letters up until their divorce in 1926. Kathleen was a saint. Anyway, I've climbed out on the psychological limb. That's my assessment. Thanks for your comments. I encourage readers to join the discussion.

ReplyDeleteIn my comment above, perhaps calling Kathleen a "saint" is too much. She was human like the rest of us. I will say that I think Carl Zigrosser said it best: "“I came to know and affectionately admire his three wives, Kathleen, Frances, and Sally,” he wrote. “It is a commonplace observation that the wives of great men generally are unheralded and uncelebrated heroines. It is true of Rockwell’s wives, even though he did voice his appreciation of them at times – not, however, at all times, not with full understanding. He made great demands upon them: they must be wife, companion, household manager, hostess, amanuensis, and secretary for voluminous correspondence. Brimming over with energy, he could and did wear out two wives. I salute all for their loyal and unselfish devotion.”

ReplyDelete