NOVEMBER 25 - 28, 2018

ROCKWELL

KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100

YEARS LATER

by Doug

Capra © 2018

Nov. 25-28, 2018

"It seems a law of fallen nature that life must always come to its being through darkness, and this makes us even more aware of its beauty. Dawn is lovelier because it comes after night, spring because it follows winter."

- Caryll Houselander

"It seems a law of fallen nature that life must always come to its being through darkness, and this makes us even more aware of its beauty. Dawn is lovelier because it comes after night, spring because it follows winter."

- Caryll Houselander

The sublime -- the beauty and terror of nature. “It rages

from the northeast!,” Kent writes on Monday, Nov. 25, 1918. “The bay is a wild

expanse of breakers. They bear into our cove and thunder on the beach. A mad

day and a mad night. “ Kent and Rockie feel safe observing the uproar from the the beach or the inside of their Fox Island cabin. The tumultuous

seas may bring back memories of that mid-September return trip to the island

when the two voyagers were nearly killed. Ambivalent memories for Kent, for he

would write on March 7, 1919 that fine adventuring is “flirting with danger,

safe enough but close – so close to death.” He's willing to take that risk, but now he has his son with him.

They’ve been packed for a trip to Seward for nearly two

weeks now. The weather, winds and seas have isolated them. But Kent was to

learn that these obstacles were a necessary part of the adventure. On January

21, 1919 he would write, “It is thrilling now with Olson absent to reflect that

we are absolutely cut off from all mankind, that we cannot, in this raging sea,

return to the world nor the world come to us. Barriers must secure your

isolation in order that you may experience the full significance of it.” But on

Nov. 25, 1918 he’s still on the verge of that revelation. They have stacks of

mail to send. “It is now my hope that a steamer will go to Seward before me,”

Kent writes – but Olson’s diary records none sighted entering the bay in two

weeks. Rockie has spent much time playing outdoors and tracking porcupines

along trails and into caves. Kent has been working consistently indoors.

“It is weeks since I’ve stopped my work even for a walk,” he writes. He does

see the irony of this aspect of his wilderness adventure. “It’s a blessing to

me to have to saw wood every day,” he admits. What bothers him most about being inside so much is the lack of light. He’s frustrated trying to paint. “My lamp

is so inadequate in this dark interior – it burns only a three-quarter inch

wick – that I can work only in black and white. But I’ve laid in the whole

picture in that way.”

Imagine retiring with the dark of night and awaking with the

light of dawn. You have lamps but oil is expensive – and candles, but they burn

fast. You rise early and work hard all day, so you retire early. Your life’s

rhythms revert to ancient times before artificial light. Perhaps you sleep for

four hours or so, and then you wake during that period between dark and

daybreak sometimes called the “Hour of the Wolf.” It can be a time when we’re

most vulnerable, when we briefly yet vividly recall the nightmare that woke us.

It’s a time when we can either be haunted by our demons or slip into a

spiritual state of meditation. For some it can become the “Hour of God.”

When you don’t have a watch or clock, you measure time in

shades of light and dark. For many days in a row you never see the sun or the

moon, just a world between gloaming and shadowy daylight. When on those rare

days you wake to clear skies, the sun won’t appear above the mountains of the

Resurrection Peninsula behind you to the east and your island until close to

noon. You have only a few hours of the kind of light you need to paint, but

you’d also like to get out on the water in your dory or hike the mountain

trails. But there’s also firewood to cut, washing, mending, cooking and other

distracting chores.

This is the experience of Rockwell Kent and his son on Fox

Island this time of year in Alaska as we approach mid-December and the shortest

day of the year. In Waking Up to theDark: Ancient Wisdom for a Sleepless Age, author Clark Strand writes: “Inside the dark we are

unprotected, and our troubles always come close. So close we can hear them

breathing. So close we sometimes feel paralyzed with fear, unable to flee or

even move. So close they could open their mouths and swallow us…or settle down

for a long leisurely gnaw.” See also At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past by A.Roger Ekirch for an excellent history of

the human journey from natural to artificial light and how that has affected our

sleep patterns and our culture.

Kent doesn’t detail for us his sleep rhythms, but he does tell us

he is often up into the early morning hours writing letters or doing other work

– perhaps sketching or planning a painting. Mystics have always cherished this

interval of night. It’s quite possible he experienced segmented sleep as most

people did in the not-to-distant past – retire early at dark, sleep about four

hours, awake for two or three hours, followed by a few more hours of sleep. The Hindu

Mandukya Upanishad describes four stages of sleep: waking, dreaming, dreamless

sleep – and the last simply called Turiya,

“the Fourth.” Strand calls it “a state beyond all of the others, but which

somehow also contains them.” It’s neither conscious nor unconscious, “a

transcendent state…known or unknown.” It can’t be articulated, only

experienced. Kent continues to read Ananda K. Coomaraswamy’s Indian Essays.

In past entries I’ve written about Kent facing his demons

late into the evening or early morning hours. But our demons can also be our

“shadow,” or as the Spanish say, our duende. On the surface, this Spanish

word is defined as a goblin, demon, or spirit. Metaphorically, it is our

inspiration, magic fire, charm or magnetism. But there’s an edge to it. Federico

Garcia Lorca, the great Spanish poet, wrote an essay titled “The Theory and Function of Duende.” He quotes flamenco singer El Lebrijano: “When I sing with duende, no one can equal me.” An old

master Spanish guitarist once said that duende

doesn’t emerge from the throat, but “surges up from the soles of the feet.” But

there can be something unsettling about duende,

too. It’s the artist’s dark creative force, his inner doubts and struggles. It

can have the provocative edge of a knife and cut deeply inward as well as

outward. It is the artist’s authenticity and passion. It cannot be forced or

feigned or even articulated. We can only accept and embrace it, feed it, and

let it happen.

While reading Coomaraswamy, Kent is asking himself: What is

art? What of the spirit? Is mysticism the belief in the unity of life? “How

hard it is to speak of these intangible things,” Kent writes, “and not use

words loosely and without exact meaning.” It can’t be put into words. “I think

whatever of the mystic is in a man is essentially inseparable from him; it is

his by the grace of God.” Who we really are, he says, our essential qualities, are the

least conscious to us. Kent continues: “The best of me is what is quite impulsive, and looking at myself for a moment with a critics eye, the forms

that occur in my art, the gestures, the spirit of the whole of it is in fact

nothing but an exact pictorial record of my unconscious living idealism.”

Much of this thought and introspection may be happening for

Kent sometime during that interval between what used to be called “first sleep”

and “second sleep” -- at a time before our world was saturated by artificial

light. The “Hour of the Wolf” has also been called the “Hour of God,” a time

when mystics from various religious traditions going back to ancient times

meditated or prayed. Kent is reading mystical, imaginative, romantic works.

He’s embedded not only in the literary past – but also in the physical past with little artificial light. In a few weeks he'll be reading Homer’s

Odyssey. Homer also writes about the "first" and "second" sleeps of night. On Christmas day Kent writes: “A few more Odysseys to read here in this

wild place and one could forget the modern world and return in manners and

speech and thought to the heroic age. That would be an adventure worth trying!

Maybe we are not so deeply permeated with the culture of to-day that we could

not throw it off. Surely the spirit of the heroes strikes home to our hearts as

we read of them in the ancient books.”

Tuesday, November 26, 1918 -- It clear and the north wind

settles a bit today and Resurrection Bay seems relatively calm. "To-night again

is so,” Kent writes, “and if I had not Rockwell on my hands to make me timid

I’d go at night to Seward.” The lights of town would have been clearly visible

to guide him – but he won’t take the risk. Olson brings Kent and Rockie

“Schimier Kase,” literally “smear-cheese” that we call cottage cheese. Today

you need raw milk to make the curd or crumbs – and water without a lot of

additives. Olson has goats and fresh stream water. Olson also gives them butter

he churns from goats milk. There's also a gift of salted salmon. “Olson was a real Santa Claus

to-day,” Kent writes. Kent’s cabin as two stoves and they burn at least one all

night, so he and Rockie cut more firewood.

Wednesday, Nov. 27, 1918 -- The day starts off lovely and

cold – but it looks to Kent like a heavy blow is on the way – so they don’t

head off to Seward. They should have gone for the wind never picks up. Kent is

now more than a bit timid about trips these excursions with Rockie aboard. He’d be

willing to take the risks himself, but not with his son. The afternoon is so

beautiful that Kent paints a small picture of “the soft haze of the

day and the loose clouds." Olson lends Kent his wooden “grub box” for the trip to Seward. The cover is fastened with a strap and buckle and

Olson tells him that every man on the Yukon has one as part of his outfit. Kent

packs it with his emergency food, letters and Christmas presents. Later that day, Rockie wraps

his stuffed animal, Squirlie, in a sweater and takes him on a long walk in the

woods. Then he draws a picture of Squirlie all muffled up as Christmas gift for

his sister, Clara.

Thursday, Nov. 28, 1918. -- “This continual waiting is

getting on my nerves,” Kent writes. It’s not only the long delay in getting to

Seward, also the concern of the potential dangers with Rockie aboard, and the

Evinrude motor. Will it work? “Most of to-day I spent tinkering with the

engine,” Kent writes. “It goes now – in a water barrel.” He goes on to discuss

the problems with engines like his – how they’re exposed to the weather and

stop when they get wet. Then Rockie has to row dragging the 100-pound motor while he tries to fix the

problem. Most are engines are hung on the stern, but

his fits down into a pocket and is difficult to lift out even on land. “So I

don’t relish getting caught with such equipment,” he writes, and adds: “I must

have mentioned, by the way, that the engine was ‘thrown in’ with the boat as of

no value.” With the motor now working, Kent is determined not to miss an early

morning weather window. He and Rockie go to bed early, plan to rise early and – if the

sea is calm – leave for Seward just before daylight.

PHOTOS

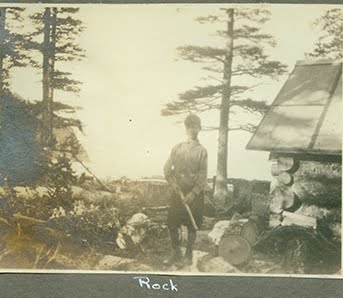

Rockie standing by the southeast corner of the cabin. Notice all the log sections around him. He and his father have been busy felling trees and breaking them down with the cross-cut saw. At left is the southern headland of their cove seen in several Kent paintings. Photo from a Kent family personal album.

Who else? -- But Rockie's stuffed animal, Squirlie. Illustration from the 1996 reprint of Wilderness.

Comments

Post a Comment