PART 1 OF 5 - THE NOT-SO-QUIET ADVENTURE

THE NOT-SO-QUIET

ADVENTURE

Unpacking Rockwell Kent's

Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska

by Doug Capra ©

2019

PART

1 OF 5

NOTE

– This is Part 1 OF 4 of a somewhat revised version of the lecture I deliver at the

Anchorage (Alaska) Museum of History and Art on Nov. 9, 2018 as part of a one-day

Kent Symposium. If you’ve been reading this website you realize there is much more

the story. This lecture focused mostly the relationship between Rockwell and Kathleen Kent as seen in their letters. While in Alaska the mail service was exceptionally slow and unreliable due to contract disputes between the U.S. Government and the steamship companies. Rockwell was away from home frequently during during the first ten years of their marriage, and he and Kathleen were used to using letters to communicate. That was impossible while Kent was in Alaska. The lag between writing a letter and receiving an answer was many weeks. There was no real communication and that became frustrating for both of them and caused much confusion and misunderstanding. I’ll post Part 2 of this

probably on Sunday, January 13, 2018.

American artist Rockwell Kent II

(1882-1971) lived one of the best documented, fascinating and yet neglected

lives of any 20th

century American artist. After stints painting on Monhegan Island off

the coast of Maine, at Winona, Minnesota, and in Newfoundland – Kent ventured

to Alaska in July 1918 with his then 8-year-old son, Rockwell Kent III, often

called Rockie. He had married Kathleen Whiting in 1908 and by 1918 had three

daughters and a son. This article focuses some of

his life before Alaska and the time he spent on Fox Island in Resurrection Bay.

He chronicled the experience in his first book, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (1920). Beneath

that book’s text, within the personal letters he wrote and received while on

Fox Island in Resurrection Bay, is the story his personal demons during that

isolation on an island in the Alaska wilderness.

The book sits on the ruins of Kent's cabin on Fox Island amidst Dwarf Dogwoods. Capra photo.

As I wrote in my foreword to the 1996

reprint of Wilderness, the book is

uplifting, inspiring and healing. It’s about art and life, childhood and old

age, alienation and integration, the inner journey, simplicity and solitude. You

can read and fully enjoy Wilderness

without considering anything I write here. But on Fox Island, when Kent refers

to his confrontation with the solitary “abyss” and describes the experience as

“the terror of emptiness,” – he’s not talking about some abstract, philosophical

concept.

Beneath

his Fox Island experience -- and the art and book that emerged from it -- lurks

the artist’s uncertainty, anger, insecurity, depression, and loneliness. There’s

a significant contrast between the uplifting redemptive story he tells in his

book and the inner agony and turmoil his personal demons bring him. As we look

back from our perspective to Kent’s rapid rise to fame during the 1920’s, we

must realize that on Fox Island he had no idea where his life was going, no

assurance of his marriage, his love affair -- or his art career.

Kathleen eventually returns to him. In

their letters, he apologizes and promises to do better. He fails, begs her

forgiveness, assures her of his love, guarantees faithfulness, and fails once

more. In 1910 Kent makes his first trip to Newfoundland to scout out the

possibility of forming an art school and colony. Kathleen and Jennie, both the

same age – about ten years younger than Kent – become pregnant within a few

months of each other. Jennie gives birth to Karl on July 10, 1911. Kathleen has

given birth to a daughter three months earlier. She and Jennie continue to meet

and correspond. Kent wants them to get along and brings Karl to visit little

Kathleen and Rockie. Neither woman is satisfied with the arrangement. Kent is considering divorcing Kathleen and

marrying Jennie.

On

Oct. 11, 1911 Kathleen writes to Kent in New York. “Rockwell, dear, you must

leave me and go to Jennie! I can’t ever be comfortable and happy with you,

thinking how I am making her suffer. I can’t be happy at the expense of someone

else…If you absolutely refuse to do this for me, you must promise to let me

sell my diamonds and economize in every possible way so that Jennie can keep

Karl with her…Don’t call this all nonsense,” she says, “for I mean every word I

say…please do as I ask…for I must make definite plans for myself.” On Oct. 13

Kent writes back: “I do realize how earnestly you mean all that you say…But

darling, let me tell you this…I really do not believe I could live if death or

anything separated us. When I actually look such a possibility in the face, it

makes life seem terrible to me. Do not, unless you really want to ruin my life

utterly, ever try to leave me.” We’ll take care of this together, he tells her.

“You cannot help Jennie by driving me off.”

To give you an idea of how quickly Kent

and Kathleen’s life becomes complicated, consider this timeline:

1907 – Kent begins a relationship with Jennie

1908 – Kent meets Kathleen and becomes engaged

Dec. 31, 1908 – Kent and Kathleen marry.

Jan. 1909 – Kathleen gets pregnant with Rockie

1909 – Kent deepens his relationship with Jennie.

Oct. 25, 1909 --- Kathleen gives birth to Rockie

July 1910 – Kathleen gets pregnant

1910 – Kent in Newfoundland

Oct. 1910 – Jennie gets pregnant with Karl

April 19, 1911 – Kathleen gives birth to little Kathleen

July 10, 1911 – Jennie gives birth to Karl

1912-13 – Kent in Winona, Minnesota

1914-15 – Kent in Newfoundland with family.

After Jennie becomes pregnant, Kent takes

most of his savings and creates a trust for Jennie -- to care for their child.

About two months later, on Dec. 11, 1911, Karl dies. In 1912, Jennie marries a

doctor, George W. Wibley, and moves to Portland, Maine. Kent claims the trust is

for the baby and now that Jennie is married -- wants the money and property

back. Jennie’s husband refuses. During 1912-13 he’s off to Winona, Minnesota to

oversee construction of some mansions. Kathleen writes, telling him “if you

really and truly love me and care for me, you will…give up Jennie and Monhegan

Island and return.” Kent writes back, “I will be good…you and you alone are in

my heart all the time…Poor little girl, you shan’t cry on my account ever

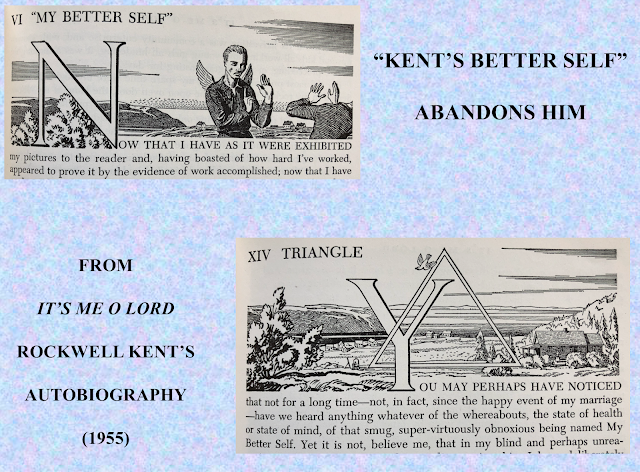

again.” Kent struggles with what he later calls his “Better Self.”

In

a 1915 court case, Jennie B. Whibley vs. William Cobb {the trust holder}-- Rockwell

Kent is a defendant. They eventually settle and Kent gets some of the money

back. So -- the Jennie issue drags on from 1909 until 1915. While in

Newfoundland in 1914 with his whole family, including a new baby, the Great War

breaks out. Kent is a Germanofile, fluent in the language and lover of the

culture. In 1915 he and his whole family are deported from Newfoundland due to

his pro-German sentiments and unwise provocations. Back in New York, he desperately

struggles to support his family and advance his art career. Kathleen has

forgiven him for the Jennie affair -- but never forgets. And then…

In June 1916 in New York, Kent meets a twenty-five

year-old -- blond and blue-eyed Ziegfeld Follies dancer, Hildegarde Hirsch.

Kent is 34. Kent keeps no secret of the affair from Kathleen. As with Jennie,

the two women are the same age and get to know each other – as Kent wants.

Kathleen’s tolerance for her husband’s transgressions diminishes. Kent’s

frustration with his failed career accelerates. He’s working at an architecture

firm to support his family and trying to keep both his wife and Hildegarde

happy -- with little time or success with his art. In June 1917 he writes

Kathleen: “I’m seriously considering not painting anymore or drawing for a long

time, but getting a job somewhere at some other work.” He even has death

wishes. He’s ripe for a new adventure. Kathleen is exasperated, too with memories

of the Jennie affair -- and now Hildegarde. This combines with her constant

struggle with money while raising four children -- often alone and separated

from her husband. She writes: “If

you want all the love that I feel, you will have to hustle some to earn it now.

This last ‘affair’ has left a scar in my life that will not soon disappear. You

cannot have the love I long to give you until you have shown me that I am not

going to be chucked aside again in a short time.” A

year later, just before Kent leaves for Alaska, she writes: “I get terribly

lonely for a man’s protection and love, and when I feel too badly I cry out -- and

I cry out for you -- for there is no one else. But at other times I fully

realize that you cannot give me the love I want ----- and I cannot give you the

love you want! You have said so.”

July

1918 -- just before Kent leaves – Rockie is with Kent in New York, and he

insists on taking his son to Alaska. Kathleen won’t go with him, even though

Kent’s mother agrees to take the children. Perhaps her experience in

Newfoundland has given her a taste of what life can be like with Kent under

such conditions. The war is still raging on. Would they be tossed out of

Alaska, too? She doesn’t want to leave the children and when she turns him

down, rather than trying to convince her, Kent immediately tries for Hildegarde

as his companion. More than anything else, Kathleen tells him, she feels, he

just wants to get away from her. “No,” Kathleen tells Kent, you can’t take

Rockie. Kent responds: “How in God’s name can you turn upon me so…Come and get

Rockwell. I’m heartbroken over it. I can’t face the thought of the loneliness

I’m going into.”

Kathleen

pleads: “I wish you and Hilda would go but leave Rockie with me. It seems

strange to me to think you are taking him away from me without my consent,

after my plainly stating I did not want him to go.” I don’t care if you take Hildegarde, she tells

him, “for I realize that she will always be a part of your life and that I must

have a husband with a sweetheart or not have him at all.” Kathleen is no longer

the innocent, naïve 18-year-old newlywed. She’s no longer the loyal wife who

remained with him despite his affair with Jennie. By 1918 she is nearing 30,

exposed through her husband’s friends to progressives and socialists, fully

aware of the women’s movement and the new emerging world. His love letters no

longer enthrall her. “Your letters…so full of love – never ring quite true in

my ears.” As he departs for Alaska, what

can she do? Rockie goes with Kent. She doesn’t really consent, just accepts

reality.

His

love letters from Alaska – to both Kathleen and Hildegarde – are overly

romantic and syrupy. As Kent’s third wife Sally said, Kent was an incurable

romantic. Unfortunately, we don’t have Hildegarde’s letters to Kent. But the contrast

in letter writing -- style, diction and syntax – between Kent’s and Kathleen’s

letters is like the difference between Mark Twain and James Fenimore Cooper; between

Longfellow and Emily Dickenson. Kent writes about flying angels sending kisses

and hugs to him across ocean and land. Kathleen

writes about giving the children a bath, trying to find money for coal -- and attending

dances with the coast guard men on Monhegan Island – which drives Kent mad. He

expects his women – both Kathleen and Hildegarde -- to be faithful and demands

passionate, adoring love letters.

Kathleen’s

letters are mostly short, scribbled at the end of a hard day trying to raise

their three daughters. His many letters to his wife are overly long and needy.

He’s a high-maintenance lover. Between Feb. 12 and Feb. 15, 1919, Kent writes

at least five letters to Kathleen totaling 44 pages of his fine penmanship which

include his anguish, his demands and criticism of her. She receives batches of

mail with several letters as long as the one below.

She misses her son deeply and still resents

that Kent took Rockie against her will. “Don’t you see, Rockwell,” Kathleen

writes, “I have shared you against my will with someone else for many years and

for the past year I have struggled to resign myself to the thought of life

without you; just as I begin to get resigned to that, you whisk Rockwell away

from me. Why should I give up so much of what there is in life. Rockwell? You

know that I love you a great deal but I can never love you as I want -- and you

want – if things continue as they are.” She wants Kent to be happy -- because

she loves him -- and their children and wants their marriage to work. But also

-- when Kent isn’t happy he can be demanding, depressed, and emotionally needy.

And overly critical. In a Feb. 9, 1919 letter Kathleen presents Kent with a

series of demands if their marriage is to survive. “Above all I want you to

appreciate my good qualities, my deeds and my thoughts – and -- I want you to

make your mother appreciate me.” Kathleen had quite an ambivalent relationship

with Kent’s mother, Sara. But that’s another story.

TO

BE CONTINUED

Comments

Post a Comment