DECEMBER 3 - 4, 1918 -- WHILE KENT IS STILL IN SEWARD

RCKWELL KENT

WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

Dec. 3-4, 2018 Still in

Seward

PHOTO

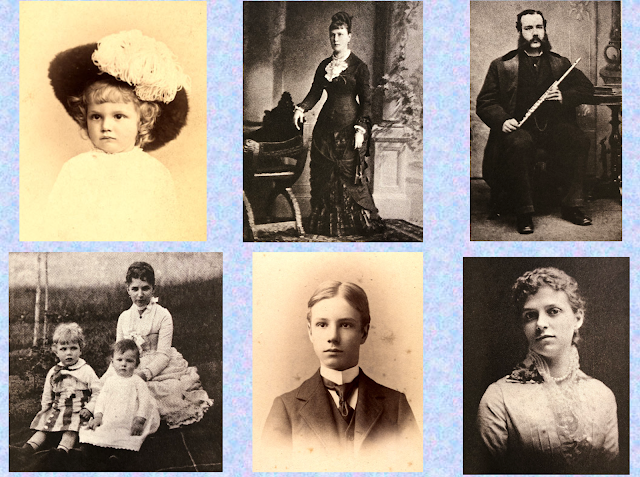

Top row from left: Kent as a child, photo inscribed to his daughter, Kathleen, in 1933; Auntie Josie Banker, Kent's mother's aunt. Kent's mother was raised beginning at age 11 by her Aunt Josie and husband, James Banker on their estate in Irvington, N.Y. Banker was a wealth capitalist connected with the Vanderbilts; Kent's father, Rockwell Kent I, died when Rockwell II was five yeas old. He's shown here with his flute which Rockwell inherited, learned to play, and took with him on all his adventures. Bottom row from left: Kent's mother, Sara Ann (Holgate) Kent with 3-year-old Rockwell at left and his brother, Douglas at right; young Rockwell; Sara's sister, Kent's Aunt Jo, an artist herself who took Kent to Europe for four months when he was 13 years old. In addition to Kent's Austrian nanny, Rosa, (not shown here) who taught him German, Kent was raised by the women in these photos.

On Dec. 3, 1918, the

day before Kent leaves Seward for Fox Island, he writes three letters to

Kathleen and one to Hildegard, and stows them aboard the departing steamship.

He’s busy during the days when in town, saving his letter writing for late

evening and into the early morning. He composes the first letter just before

midnight. He’ll make sure every steamer leaving Alaska has letters for Kathleen

so at least every other one should be a happy letter. Though her recent letters

to Kent have been disturbing, he has confidence those he gets in January will

be more positive but has little assurance of those now waiting in Seattle for

the trip north. After all, didn’t he open his heart to her in that Nov. 30the

letter, revealing his new insights and how he has changed? “Tell me,” he

writes, “do you believe it, that new self of mine?” He asks for a special

letter from Kathleen, more loving, hopeful, and appreciative. “What should it

be?” he asks. He’ll summarize what her letter should tell him, giving her an

outline to follow: “It shall tell me of all you hope from me, of all you

picture for us two. If you’re longing for the happiness that I alone can bring

you it shall paint your vision of our future life together – tell me of the

days and companionship and the nights when our souls open flower-like and

mingle and are one. These things are in your heart. Unlock it, my darling, your

sweetheart knocks.” He finishes this letter at 12:30 a.m. December 4…

…and starts on the next one (though it’s

still dated Dec. 3rd). His mood becomes darker during the Hour of

the Wolf. “Maybe I’ll not be able to endure it longer without you,” he writes.

“Do you know that now it seems impossible? But you must tell me to be strong

and stick. You must write me longer and longer letters. Know that my strength

of purpose will be failing. Show yourself so true, so beautiful and steadfast

in your love, so ardent for me as the spring warms your blood – that anxiety

cannot trouble me and my thoughts of you can be at least serene.” Kent asks Kathleen

to imagine a romantic camping trip: “How

we’ll explore by day and night sleep together in our little tent somewhere

beneath the trees. And the little insects will buzz and sing to us two locked

together under the warm covers in the double darkness. Ah, Kathleen. What a

honeymoon for us at last! To do this is my promise and my hope if only you will

love me.” But if she doesn’t love him fully, if she isn’t true to him, the

consequences will be severe: “I’ll go forever out of your life and beyond the

knowledge of men. My fate is absolutely in your hands, remember it, and to each

other we must tell the truth.” What is he saying here? If I kill myself you’ll

have only yourself to blame? And If I do, what will happen to Rockie?

His darkness continues in the third letter

of Dec. 3rd. “I woke up last night in bed shouting, in my nightmare! a man whom

I will not mention has taken advantage of my absence to seduce you.” Kent

reminds here there are men who will “steal a wife and deceive the husband.” In

his nightmare, Kathleen yielded to the seducer, “…hanging affectionately on his

arm and getting into a cab.” He almost packed his bags, grabbed Rockie and left

Alaska for New York. “What if I had done it,” he asks Kathleen. “It would ruin

our lives in the failure it would mean of my opportunity here!” Kent wants

Kathleen to write him immediately to renew the promises she made to him about

being faithful.

Keep in mind that Kathleen won’t get

this letter for at least two weeks and it will be a month at best before Kent

gets her reply. There’s no real communication between the two.

And what about Hildegarde? Between the

time Kent left New York in late July 1918 and Oct. 28th – he has

written at least 29 long, romantic letters to her. The last letter he writes to

Hildegarde is on Oct. 28th. Through the end of November, Kent may

not have received any in return. But he did receive that disturbing Nov. 21st

letter from Kathleen describing what she learned about Hildegarde on a trip to

New York. This is most likely why Kent has been writing so many both loving and

disturbing letters to his wife. He needs love, loyalty and adoration from at

least one woman. This may be why we see Kent going back and forth between regret,

apologies, threats, and sweet loving making in his letters to Kathleen. While

in Seward between Nov. 30th and Dec. 4th – Kent gets two

letters from Hildegarde that had been sent to him in Yakutat back in August.

Only two letters. On Dec. 3rd from Seward, in between the letters to

Kathleen, he writes to Hildegarde:

“Sweetheart:

In

a little while I go {back to Fox Island}. This one more letter can be written.

I am continually uneasy in my mind about you. And to-day the Yakutat letters came

– only two of them – the only ones you wrote me for a whole month. You were in

the Adirondacks. Hildegarde, have you been true to me? Do not deceive me. Oh, I

mustn’t question you but leave it to your honor to tell me even if you have

done wrong. Now I feel so alone. From the only one, I believe, who loved me I

have cut myself off. Can you ever, ever forgive me? You must. I am really doing

what I know to be best. Do be good, my sweetheart, oh my dear love, be always

sweet and good. Lovingly, Rockwell.”

Back to the last letter Kent writes to

Kathleen on Dec. 2rd – He tells his wife that he hasn’t written to Hildegarde

in six weeks. The affair is over, but he doesn’t know how to tell her. He hopes

he she’ll get the message with his silence. Hildegarde’s letters have been “beautifully

and touchingly true, particularly of late, making it difficult for Kent to be

direct. He apologizes to Kathleen for returning that “poison” letter she wrote

to him about Hildegarde’s infidelities, but he can’t allow his wife to say such

things about the other woman he loves. And, he adds, he’s lost faith in Kathleen’s

love and constancy. Now, seeing little hope in Hildegarde’s love and knowing she

will never join him, he makes Kathleen feel guilty about not joining him on Fox

Island. You chose to stay in New York. Your choice not mine. That was an

expensive choice. You would have saved us money if you had come to Alaska. “You

should have thought of this,” he chides, “you would have thought of it HAD YOU

WANTED TO.”

Kent continues – But this is a love letter, “not a scolding or

complaining one.” As of the moment, Hildegarde is a fading attachment so he

must try to woo his wife again. “Oh, Kathleen, but I love you so whole

heartedly. You do not know half of my love and I hope to heaven I don’t know

one twentieth of yours. On the island see me loving you ever (more) dearly telling

Rockwell of your making with him grand plans for the future of us all, kissing

him for you and sleeping with my arms about him and dreams of you in my heart.

Sometimes I will be unhappy, terribly so, for homesickness and for lack of love

and will feel bitterly that you have told us so little. That you can help in

the letters you will write from this time on. Let nothing divert you from it.

It seems to me that this must hold for both of us, that only the sternest

necessity shall turn us from our letters to each other which must be to us what

prayer is to devout worshipers of God. Goodbye dear sweet wife of mine with

eternal love, deep, deep, true love for you. From your Rockwell.

Second thoughts. Kent has more to say, so there appears writing

on the margins of both sides of this last page. “I have written Hildegarde that it

is over. It is a hard thing for me to do. She has written faithfully and

eloquently and so puts you to shame. The letters have been true whatever she

may have done. And let me tell you mother dear that I would rather have the

devotion of a sinner to comfort me in my loneliness than the careless neglect

of another even if she still be my faithful wife. But neither {NEITHER is dark

and big} will do for me. You must love me and be in every act and thought true

to me. And I will be to you, that I promise. Help me then for it is vastly

harder for me than for you… I don’t expect you to write as I have written. Your

nature is different and you must keep it regardless of me…I’ll do everything in

my power to make you make your dear life happy. And what is beyond my power to

do is still yours to complete for me. Goodbye dear child. Ever your Rockwell.

We’ve seen this again

and again in Kent’s letters – but here it becomes especially clear – not only

the creative energy he derives from being in love, but also the synergy he

demands from his lovers. His third wife Sally knew this about him and revealed

it in her introduction to the Companion Booklet to the Facsimile Edition of the

story and handmade book Kent created for Hildegarde in 1917 – The Jewel: A Romance of Fairyland

(1990). Sally wrote: “What is important

to consider in reading and enjoying The

Jewel is that Rockwell Kent was an incurable romantic and that his creative

energies were heightened by the focus of being in love. He was that way to the

end of his long and exceptional life. Nature, of course, in all its untamed and

uncharted magnificence was the great stimulus to his art. But one has only to

look at the range of his artistic work to see how often the women in his life

were subjects and beneficiaries of his creative genius.”

Yes, his women do

benefit in some ways but they also pay a heavy price. Kent’s passion demands

adulation, reverence, idolization, and praise in return for his love – and especially

loyalty. Their worship provides him dynamism, vitality and self-confidence. Since

his affair with Jennie, apparently, Kent can’t depend upon one woman to

consistently supply this adoration. In his Alaska letters to Kathleen, he often

compares her “hurried,” “careless” and critical letters to Hildegarde’s who

writes what he wants to hear. But he hasn’t heard from her recently and is

concerned. We don’t have Hildegarde’s letters for comparison, but Kent’s claims

seem plausible. The two women own distinctive perspectives and histories with

him. Being Kent’s wife with the care of his children is quite different from

being his amour. Behind Kent’s mask of bravado and manliness lurks a soul whose

relationship with women is needy, exhausting and high-maintenance.

Kent is not unique in

this regard. We see it in other men – artists writers and other creative geniuses

with their relationships with women. I’m reminded of the National Geographic series

on public television titled Genius

one about Einstein, the other about Picasso. There are many other examples. We

can never fully get into the minds of these men and women.

Does Kent’s upbringing help explain his tendencies? Perhaps. His father died when he was five years old, and he grew up without the influence of a strong male model. In his Kent biography, David Traxel gives us an interesting insight: “It had been thought best to keep the reality of the father’s death from the children.” Their father was just on another trip, they were told, and would eventually return. As the oldest, Rockwell began to intuit the truth. Traxel continues: “His mother, cold and controlled, did not offer much emotional support.” Young Kent had nightmares of death and began to sleepwalk. “He felt abandoned,” Traxel writes, “his loneliness intensified by the family’s snobbery.” In his autobiography, Kent recalls how his mother would not let him play with the local children. They lacked the social status, even though the Kents at that time – were impoverished members of the gentry.

Does Kent’s upbringing help explain his tendencies? Perhaps. His father died when he was five years old, and he grew up without the influence of a strong male model. In his Kent biography, David Traxel gives us an interesting insight: “It had been thought best to keep the reality of the father’s death from the children.” Their father was just on another trip, they were told, and would eventually return. As the oldest, Rockwell began to intuit the truth. Traxel continues: “His mother, cold and controlled, did not offer much emotional support.” Young Kent had nightmares of death and began to sleepwalk. “He felt abandoned,” Traxel writes, “his loneliness intensified by the family’s snobbery.” In his autobiography, Kent recalls how his mother would not let him play with the local children. They lacked the social status, even though the Kents at that time – were impoverished members of the gentry.

Kent was the first

born, raised, disciplined, and doted upon by his mother, his mother's sister, Aunt Jo, his

nurse, Rosa, and his mother's Aunt Josie Banker. He was a difficult child, strong-willed and defiant. Traxel adds “rebellious” and “intractable.”

Young Kent learned how to manipulate these women to get his way. As Traxel writes,

the boy “enjoyed all the secure material comforts of the late Victorian middle

class…It was a home of genteel culture and refinement…The family’s Austrian

maid, Rosa, bore responsibility for the day-to-day care of the children. She

developed a special relationship with little Rockwell as she taught him German,

which he spoke before English…” There were other children. Kent’s brother

Douglas was two years younger, and later came a sister, Dorothy. “He teased his

young sister unmercifully,” Traxel writes, “making fun of her posture, her

speech patterns and the size of her teeth.” She recalled this treatment all her

life. In his autobiography, In his autobiography, Kent writes about he and his male friends at the Horace Mann School, and their misogyny. His relationship with women was complex

– and as I quoted Kent in a letter he wrote to Kathleen, throughout his life, Kent's relationship with his mother was ambivalent.

Comments

Post a Comment