MARCH 28, 1919 WANTED -- AN EXPLANATION

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

Friday -- March 28, 1919

WANTED – AN EXPLANATION

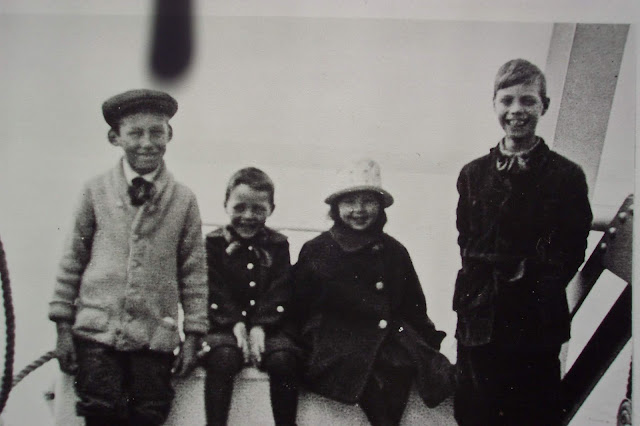

ABOVE -- Eight-year-old Rockie (at far right) with some children he has befriended on board the steamship to Alaska. Photo by Rockwell Kent, courtesy of the Rockwell Kent Gallery, Plattsburgh State University, Plattsburgh, N.Y.

The Thursday, March 27 edition of the Seward Gateway with Kent’s

Praise for Alaska letter came out late that afternoon. We can easily imagine

the varied reactions it caused. That evening around dinner tables

and in saloons it must have been a topic for conversation. The discourse probably

continued the next morning in the cafes over coffee and donuts. People took

sides. Who was this peculiar artist who had spent the winter on Fox Island? The

old guard like Hawkins, Brownell, Graef, and the Roots who had socialized with

him perhaps tried to explain. They could understand what he was talking about,

the basic issue that had split the town a few years earlier. But now it was

time for healing and working together. Not everyone agreed with territorial

prohibition, the draft or gratuitous snooping. But it was difficult to maneuver

around Kent’s use of the expression “the menace of Kaiserism,” and words like “sheep”

and “tyranny.” Some saw the letter as a back-handed compliment – and even today

many Alaskans don’t appreciate advice from Outsiders who have little knowledge

of conditions here. Just read the Letters to the Editor in Alaska newspapers.

Many begin with sentences like – “I’m a lifelong Alaskan and…;” or “I’ve lived

in Alaska (Insert) years and…).

Perhaps rumors circulated around town about a new local school

teacher – Mary Baen Wright -- who was composing a letter in response to Kent’s Praise for Alaska. Few probably knew of

its specific contents but if human nature hasn’t changed much in 100 years, all

varieties of gossip circulated around town. Could it have something to do with

his young son? People knew Rockie occasionally visited the school as a guest of

other children when he was in town with his father.

BELOW - From the August 28, 1918 issue of the Seward Gateway. Ironically, this is the day Kent meets Olson, discovers Fox Island, and decides to settle there for the winter.

On Sept. 28, 1918 Kent is settling in on Fox Island, commenting on the river otters old Olson has been watching. That day, the Seward Gateway publishes some brief anecdotes about events happening in the Seward schools. Among the stories is the one below.

In seventh year class:

Miss Wright: "Name some dead languages."

One pupil: "Latin."

Another: "'Greek."

Another: "German!"

Miss Wright: "Good! Go to the head of the class.

Miss Wright was born at Decatur, (Greensburg)

Indiana in 1886, daughter of Samuel B. and Mary E. Wright. An article by Pat Smith in the July

28, 2010 Greensburg Daily News tells us this about her: She was “the first woman to study

journalism at Indiana University, the first woman to serve as editor of the

university yearbook, and the first woman to serve as editor of the campus

newspaper... She was also the first person to start a

school in what is now Anchorage, Alaska where she taught Eskimo children. On a 1924 passport form (She is now married to Alexander Watts) it says she was in Alaska between 1918 and 1920. Below is her passport photo as she embarks on a trip to England, Scotland and Europe.

BELOW -- A 1910 photo of Miss Wright from her Indiana University yearbook.

Miss Wright probably went to Anchorage the year after

she taught in Seward. There she would have taught children of businessmen and

women as well as those working for the Alaska Railroad. Smith also writes that “at age 17 Mary Baen was credited with being

the youngest teacher in Decatur County for many years. She had graduated from

Greensburg High School in 1903 and started teaching at age 17 that fall. She

received her degree from I.U. in 1910 and her master's from U of Oregon in 1942… Mary

Baen and first husband Alexander Watts had a child that died in infancy. She

married Charles Thompson of Greensburg who died two years later. They had a

daughter named Mary Alaska {Thompson}. Mary Baen died in 1963 in Oregon where

her daughter, son-in-law and their four children lived. Her sisters were Mrs.

Marion McCormack and Mrs. Roy Williams both of whom died before Mary Baen. Below is her obituary in the Sept. 18,

1963 issue of the The Indianapolis Star.

I’ve learned that she started writing at

an early age and published articles and short stories in magazines like the

Saturday Evening Post. Her father was a physician and died the year before she

came to Alaska. A death notice in the Feb. 15, 1917 Eugene, Oregon Morning

Register notes that “he was one of the pioneers of the prohibition movement in

Indiana.” I bring this up because I believe her family were Methodists, a

denomination quite active in the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)

which was organized in Ohio in 1873. In 1918 there were three churches in

Seward -- Roman Catholic, Episcopal, and Methodist. By far the Methodists held

the most influence. The first full time Methodist minister, L.N. Pedersen,

arrived in 1905. His wife Frances was deeply involved with the WCTU. The Seward

Methodist women were extremely active in Seward, and with other members of the

WCTU pushed for the passage of Alaska's 1916 Bone Dry Law. They also represented a

powerful lobby for giving Alaska women the right to vote. When Alaska became a

territory in 1912, the first president of the Territorial Senate was Seward

attorney L.V. Ray. His wife, Hazel, (and their daughter, Pat Ray Williams) told

me that L.V. left for the legislative session in Juneau knowing that he’d

better get a bill passed to give Alaska women the vote if he wanted to return

to Seward. It was the second bill passed by the Alaska Territorial Legislature

in 1913.

All through Friday, March 28, 1919 many

in Seward waited patiently for the afternoon Seward Gateway to hit the streets.

By now many varied rumors probably circulated about who would respond to Kent’s

letter and what he or she would say. When the newspaper came out, this is what

they read on the front page:

Wanted -- An Explanation

(Editor of the Gateway): --

The phrase, "the menace

of Kaiserism," in Mr. Rockwell Kent's cryptic article in Thursday night's

Gateway, strikes me as inconsistent with a happening at the schoolhouse last week.

It was recess time. I was interrupted in reading a book by a crowd of excited

boys trooping up before my desk and clamoring, "Tell her what flag you

like best." They were dragging a boy who was a stranger to me -- a rather

tall, intelligent looking lad of about nine years.

"The German," replied the boy.

Never suspecting but that the affair was part of a game, or a bit of harmless hazing on the part of my boys, I gave the young stranger a little slap with my book, saying, with mock severity; "You'd better not talk like that around here," and resumed my reading. Later I learned that the boy, who is not now attending the school, was the son of an excentric {sic} artist from New York, living on an island near Seward; that he had never been sent to public school before; that he had some knowledge of the German language, and that he had meant what he said -- I recall how earnestly the wide blue eyes met mine. Later, Miss Kendall, a teacher, heard him say, "I don't hate any flag except the English."

How monstrous to hear an innocent child voicing the sentiments of the frightful "Hymn of Hate" whose author, Lissauer, was decorated by the world's arch-criminal.

"Hate of the heart and hate of the heart --

We have one foe, and one alone -- England!"

That is the spirit which dropped bombs on English schoolhouses and hospitals and nailed the shrieking Canadian soldiers to the cross!

Hymn of Hate against England

by Ernst Lissauer.

Translation by Barbara Henderson, as it appeared in THE

NEW YORK TIMES of Oct. 15, 1914.

French and Russian, they matter not,

A blow for a blow and a shot for a shot!

We love them not, we hate them not,

We hold the Weichsel and Vosges gate.

We have but one and only hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone.

He is known to you all, he is known to you all,

He crouches behind the dark gray flood,

Full of envy, of rage, of craft, of gall,

Cut off by waves that are thicker than blood.

Come, let us stand at the Judgment Place,

An oath to swear to, face to face,

An oath of bronze no wind can shake,

An oath for our sons and their sons to take.

Come, hear the word, repeat the word,

Throughout the Fatherland make it heard.

We will never forego our hate,

We have all but a single hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone —

French and Russian, they matter not,

A blow for a blow and a shot for a shot!

We love them not, we hate them not,

We hold the Weichsel and Vosges gate.

We have but one and only hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone.

He is known to you all, he is known to you all,

He crouches behind the dark gray flood,

Full of envy, of rage, of craft, of gall,

Cut off by waves that are thicker than blood.

Come, let us stand at the Judgment Place,

An oath to swear to, face to face,

An oath of bronze no wind can shake,

An oath for our sons and their sons to take.

Come, hear the word, repeat the word,

Throughout the Fatherland make it heard.

We will never forego our hate,

We have all but a single hate,

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone —

_ENGLAND!_

In the Captain's Mess, in the banquet hall,

Sat feasting the officers, one and all,

Like a sabre blow, like the swing of a sail,

One seized his glass and held high to hail;

Sharp-snapped like the stroke of a rudder's play,

Spoke three words only: "To the Day!"

Whose glass this fate?

They had all but a single hate.

Who was thus known?

They had one foe and one alone--

_ENGLAND!_

Take you the folk of the Earth in pay,

With bars of gold your ramparts lay,

Bedeck the ocean with bow on bow,

Ye reckon well, but not well enough now.

French and Russian, they matter not,

A blow for a blow, a shot for a shot,

We fight the battle with bronze and steel,

And the time that is coming Peace will seal.

You we will hate with a lasting hate,

We will never forego our hate,

Hate by water and hate by land,

Hate of the head and hate of the hand,

Hate of the hammer and hate of the crown,

Hate of seventy millions choking down.

We love as one, we hate as one,

We have one foe and one alone--

_ENGLAND!_

It’s June 26, 1985. I’m in Massachusetts visiting my family – driving a

backroad I’ve traveled hundreds of times in the past. My wife, Cindy, sits

beside me and my year-old son Nathan babbles in his car seat behind us. I’m

deep into my Rockwell Kent research writing an article for The Kent Collector about the artist’s ugly confrontation with the

Seward Gateway and local teacher Mary Baen Wright in March 1919. It’s new,

unpublished information. Kent doesn’t include it in Wilderness and – to my

knowledge – never put it in writing at all. I have the teacher’s side of the

story. I can’t get Kent’s account anymore, but Rocky is living in Uxbridge,

Massachusetts. I can get his version if he’ll meet with me.

I call him from where I’m staying on Cape Cod. He’s quite excited to hear

from an Alaskan familiar with Fox Island and is anxious to talk with me. He

lives in an old farmhouse on the Uxbridge Road in Massachusetts, a narrow

roadway between and Westboro and Uxbridge and surrounding towns. I know the

road well. Though I was born in Boston and lived in Worcester until I was about

7 years old, I later moved to Westboro where I was raised. During my

undergraduate years at Northeastern University, I worked for the Worcester Telegram & Evening Gazette

in some of their suburban offices like Uxbridge and Whitinsville. I drove that

road back and forth between Westboro and Uxbridge many times and passed Rockie’s

house. At the time, of course, I knew nothing of Rockwell Kent. Synchronicity

at work.

As I motor up the driveway to Rocky’s house with my wife and year-old son,

my first thought is that I had passed this place many times before. As we exit our car, a group

of chickens meet us, the first my young son had ever seen. Rockie meets us at the

door. Inside, I notice his father’s art

on all the walls, sketches and a few paintings. After introductions and some

brief discussion, my wife took our son outside to entertain the

chickens.

BELOW -- Rockie later in life with one of his animals. Photo courtesy of his son, Chris Kent.

I asked Rockie if he recalled the controversy in Seward. What

controversy? his eyes responded. I gave him a brief explanation,

then handed him the newspaper articles. He sat and read, absorbed in the story.

“I never knew all that happened,” he told me. He remembered the event at school

vividly yet differently. The teacher passed around a Book of Knowledge, he

recalled, and the children were asked to select their favorite flag. Young

Kent, fascinated with the eagles he had seen on Fox Island and the shores of

Resurrection Bay, quickly found a flag featuring that intriguing bird. Far from

his mind at the time was the German Imperial Eagle.

I had read Rockie’s memoirs in issues of The Kent Collector from the 1980’s. He

had made no mention of the incident. Apparently he rewrote those memoirs and they

were published in the Fall 2014 issue. He does mention it there.

That evening of March 28, 1919 – Miss Wright’s letter

is probably a topic of discussion in saloons and at dinner tables. Those who

have befriended Kent know he is scheduled to leave Seward via steamship the next

day. Will he reply? What will he say? What can he say if this story is true?

Some may think it unprofessional to drag a child into such a political fray.

But for now, people must wait yet another night and day while maneuvering the

rumor mill before they get an answer.

Comments

Post a Comment