August 28, 2018

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

August 28, 2018

"The wilderness hath charms. To go to it is to return to the primitive, the elemental. It is reached by the trail, the oldest thoroughfare of man. The trail breathes out the spirit of romance...The wilderness still exists...Away off, far from the haunts of man, you pitch your camp by some cool spring...Dull business routine, the fierce passions of the market place, the perils of envious cities become but a memory...At first you are appalled by the immensity of the wilderness...Almost imperceptibly a sensation of serenity begins to take possession of you...Your blood clarifies; your brain becomes active. You get a new view of life. You acquire the ability to single out the things worth while. Your judgment becomes keener...You learn how simple life is when reduced to its elements. The complexity of the life you have left behind becomes apparent. Slowly you become like the land you are in...The wilderness is moody. At times the silence is terrifying...The noises of the wilderness at night are many...The wind rushing through the trees sounds like the beating surf...Overhead the stars shine with brilliance...The pastimes of men in the wilderness are of the manly order...The wilderness will take hold of you. It will give you good red blood; it will turn you from a weakling into a man. It will give you a broad view of human nature and enlist your sympathies in its behalf...You will soon behold all with a peaceful soul."

-- George S. Evans, "The Wilderness," Overland Monthly, 43 (1904), 31-33.

Chapter II of "Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska" is titled ARRIVAL. “Our journal of Fox Island begins properly with the day of our final coming there,” Kent wrote. “August the twenty-eighth, 1918.”

Well, maybe.

Kent was a talented writer and knew how to be selective, how to condense, and how to tell a compelling story. You’ve already read here some of the personal and professional aspects of his life he omitted – his wife and children on Monhegan Island off the coast of Maine; his lover, Hildegarde Hirsch in New York; and his friend and editor, Carl Zigrosser. To Kent’s credit, what makes his Alaska book work is its focus, enthusiasm, and inspiration. It doesn’t include the whole truth of his sojourn, but what truth it covers is authentic.

Back in Seward after the Sunday, August 25th afternoon picnic, Kent had to get permission to stay on Fox Island and find a way to make it financially sustainable. On Monday, August 26th, the Seward Gateway noted that “Berry pickers were down the bay and out in the hills yesterday and all returned with full buckets of blue berries.” Kent had come back with something more important, so early that morning he probably headed to Brown & Hawkins Store to talk with the financer of Olson’s fox farm, Thomas W. Hawkins. As former Seward Mayor, H. Russel Painter remembers him in later years, T.W. -- as he was called -- may have been standing on the sidewalk in front of his store greeting customers as he often did mornings. He was a figure to behold, standing upright in his three-piece suit, his thumbs hooked to his vest pockets and his gold nugget watch and chain clearly visible.

Maybe 20 years ago -- I’m sitting on a sofa at Virgina Darling’s apartment above the Brown and Hawkins store in downtown Seward. Virginia is the daughter of Thomas W. Hawkins, one of Seward’s founders. She has been a major source for local history. The old timers don’t always remember specific dates and other details. I can often find those in other sources. They do give me a sense of what life was like in the past, how people felt, their attitudes and hopes and fears. One thing about Seward I learned when I first arrived – it’s an old town for this part of Alaska and quite a few of old timers were still alive. Virginia remembered Rockwell Kent and Lars Matt Olson. We’re looking through an old family photo album and she’s telling me stories. Hawkins’ Family tradition reveals that T.W. helped finance Kent. That makes sense. The work of a New York artist could help Seward promote itself as a place to invest and settle – especially now during the construction of the Alaska Railroad with the infant town of Anchorage competing with the established port of Seward. In exchange for this help, Kent painted a portrait on plywood of little Virginia Darling which now resides at the Resurrection Bay Historical Society Museum.

Her father, T.W., local entrepreneur and partner in the Brown and Hawkins mercantile encouraged Olson to file a homestead on Fox Island in 1915. Businessmen like Hawkins had the foresight to invest in many ventures knowing most would fail but hoping enough would succeed to produce a profit to cover the losses. Fox farming was one such endeavor. Olson became the caretaker and Hawkins the financier for the Fox Island operation. Olson often visited the Brown & Hawkins store during his trips to town – probably discussing business with T.W. and later sitting around the woodstove swapping stories with customers and clerks. Kent writes about one such visit in his book. Virginia recalled one childhood memory of watching Olson around the woodstove at Brown & Hawkins weeping as he told about one of his goats that had died after eating some paint from an open can he accidently left out. “He loved those goats,” she told me, and recalled another vivid memory of his strong odor. “You could smell him coming,” she said. Living closely with fox, goats, hares, and other animals had its disadvantages.

“Let’s skip the days it took to get established there,” Kent wrote in his autobiography.

Let’s not.

He probably sought and received much advice from local sourdoughs. Although Seward was only twelve miles north of Fox Island, he wouldn’t be able to just come and go as needed during fall and winter. Old timers no doubt warned him about the dangerous seas, especially after they saw the “splintery” dory he purchased for $50 with an old engine thrown in that didn’t work. “Our little patched-up three-and-one-half-horse-power Evinrude motor at the stern,” Kent called it. The antique, beat-up Evinrude was a large commercial motor not built for such a small vessel. He took it to Graef and Boehm to make it run. As Kent was to later learn, when it broke down – which it often did -- it was too heavy to haul in the boat, a hundred pounds he wrote. He and Rocky would have to row with the drag of that weight.

It took Kent two days to gather his first outfit. Rocky’s memory of that busy time is jumbled, but he did remember the “smells of leather boots and yellow oilskins” at Brown & Hawkins General Store. As they wandered the town meeting people, collecting materials, and telling of his plans, the two attracted attention. Seward was (and still is) a small town, and the town’s professionals – doctors, lawyers, bankers, teachers – were well-read. Many subscribed to Outside newspapers and magazines like the Literary Digest, Harpers, and the Atlantic. Some may have recalled reading about a socialist artist by the name of Rockwell Kent. Others may have even remembered a series of stories about his Newfoundland departure, like a syndicated piece published in 1916 that ran throughout the country:

“Rockwell Kent, an American artist, has returned to home in West New Brighton, N.Y., after having been expelled from Newfoundland, under the defense of the realm act, on suspicion of being a German spy. He endeavored through the state department to begin a suit for $5000 damages against the Newfoundland government. He was informed, however, that the state department would not support his claim.”

I have no doubt, as Kent reports, that at 9 a.m. on Wednesday, August 28, 1918 – probably with the help of friends he had made – Kent hauled his outfit down to the shores of Resurrection Bay, slid his dory into the water, clamped on the heavy engine, and began the loading process. But as Rockie recalled, there would be other trips back and forth with supplies. He and his son most likely had a number of curious spectators observing that departure. Some in Seward had embraced this artist-adventurer from New York willing to endure a winter on Fox Island with his young son and the bizarre old Swede. He became their friends and visited them throughout the winter. Others merely questioned the peculiar enterprise while gazing at his small, packed dory with its heavy engine at the stern. How would it all turn out, they may have wondered? Perhaps he was just plain whacky, a few may have thought.

By 10 o’clock on that Wednesday morning the loading was complete. Kent and Rocky hopped into their dory “with little room for ourselves” and pushed off into Resurrection Bay. The day was cold, foggy, and overcast with drizzling rain. They headed for Fox Island “with the little motor running beautifully.”

Later that afternoon the Seward Gateway hit the streets. If Kent had been in town to read it, he may have noticed that forty-one members of the Seward Home Guard met the night before to drill. There was no lagging, the paper reported. Men from 18 to 45 years old would now have to register for the draft. That meant him. A few weeks earlier, a brief story reported that two new school teachers were heading north aboard the steamer Alaska. One of them, Miss Mary Baen Wright from Indiana, was in charge of grades six through eight. She had arrived and her classes were in session on Aug. 28. The Gateway published a small story about her intended to be both humorous and cautionary. Miss Wright asked her seventh graders, “Name some dead languages.” One student replied “Latin.” Another said “Greek.” She gave them no response. The third student gave her the answer she was seeking. “German,” he said. “Good!” Miss Wright said in praise. “Go to the head of the class.”

Her name would have meant nothing to Kent at the time, but it would return to haunt him in late March 1919.

Meanwhile Kent crouched uncomfortably at the stern operating their bulky Evinrude engine which puttered away contentedly as they hugged the western shore heading south. Rocky sat packed between boxes, suitcases, duffle bags and stoves as they drove into a miserable drizzling rain in the fog. Three miles out they heard a bang, a whir and the motor raced. Then silence. They were dead in the water. Fortunately, the sea was calm -- otherwise, loaded as they were -- they might have capsized. Now what?

They had found a place to spend the winter. Now all they had to do was get there. They found the buried oars amidst all the other supplies and started rowing. Amid the drizzle and the fog Rockwell Kent’s “quiet” Alaskan adventure had begun, but perhaps it wouldn’t be as peaceful as he expected.

PHOTOS

Thomas W. Hawkins of Brown and Hawkins General Store in Seward. The original building still stands. Photos courtesy of the Resurrection Bay Historical Society and the Seward Community Library.

Kent took this photo of Lars Matt Olson inside his cabin with his two favorite goats, Nanny and Billy. Courtesy of the Rockwell Kent Gallery.

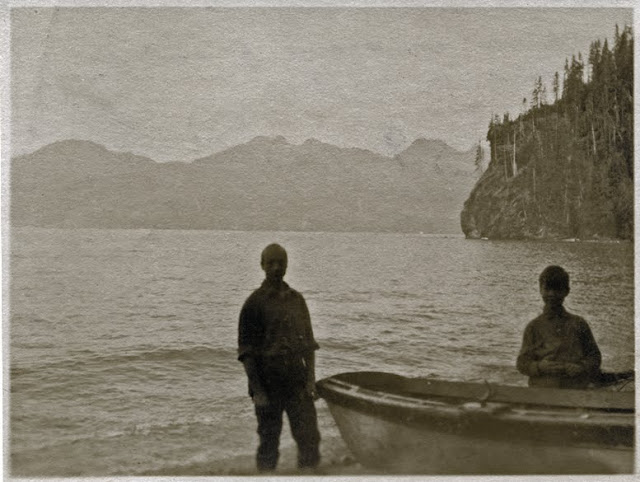

One of only two photos I've been able to find of Kent and Rockie with their boat. This one was taken on Fox Island from their cabin site with the northern headland in the background. Notice the engine isn't in the boat. Thanks to Jake Wien for sending me this photo.

This story about Kent's Newfoundland expulsion was syndicated in many newspapers across the country in 1916. Most likely some in Seward had seen it.

A college photo of Seward teacher Mary Baen Wright (1886-1963). She became a prominent journalist, and I think it's likely that in later years as Kent became famous she wrote about her 1919 confrontation with the artist in Seward. I'm trying to contact her descendants. She was born and raised in Greensburg, Indiana. Her first husband was Alexander Watts. Her second husband was Charles Thompson. They had a daughter named Mary Alaska Thompson. I'd appreciate any help tracking down her descendants.

Comments

Post a Comment