SEPTEMBER 22-24, 2018

ROCKWELL

KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100

YEARS LATER

by Doug

Capra © 2018

September

22-24, 2018

During

this period 100 years ago, Kent and his son experienced an especially rough

storm season that brought torrential rains that resulted in damaging floods for

Seward. Kent is in Seward now, probably staying at the Sexton Hotel. He’s

gotten to know photographers Sylvia Sexton (whose father, George, owned the

hotel) and Thwaites. He has also got to know Otto Boehm, a German mechanic who

worked for hardware-man Jacob Graef, who sold Kent his dory and engine; Thomas

Hawkins of Brown and Hawkins Store – he financed the fox farm and partnered

with Olson; William E. Root, the postmaster, and his wife, Frances; and Don

Carlos Brownell, one of Seward’s early pioneers and later Seward mayor and

Territorial Senator.

Kent is

also courting the Seward Chamber of Commerce and they’re interested in him. The

Alaska Railroad is still under construction in 1918, and Seward has been

observing the rapid growth and political clout of the tent city along Cook

Inlet at Ship Creek. The town is called Anchorage. Beginning in 1915 when

Seward was named terminus of the new Government Railroad – especially after

1916 when Anchorage got its own newspaper -- nasty barbs began flying back and

forth between the two towns. The fight was over coal and port access. For those

interested in Alaska history and a detailed economic and social context of

Kent’s stay in Seward, here’s an article I published about this issue.

Kent and

Rockie motored to Seward on Sept. 18, 1918. They left on Sept. 24th.

During that time, Olson wrote brief entries in his journal

n

W.

18. – Wary fear day. Mr. Kint and he Boy went to seward this morning.

n

T.

19. -- raining heard all day steamer

from West going to seward 4 P.M.

n

F.

20. – raining heard all Day.

n

S.

21. – Wary rof rainstorm from Soght Est. Wullys all over.

n

Sun.

22. – Steamer from West going to Seward 2 P.M. the tied vary Hie Comes clear up

in the the gras and the surf are Stiring up all the Driftwood along the shore.

raining lik Hell.

n

M.

23. – raining all Day.

n

T.

24. – Snow on top of the mountains on the mainland a tre masted skuner from

West going to Seward. toed by som gassboth raining to Day egan. Mr. Kint and

son got ome to the island this Evening.

Yes – as

Olson wrote – “Mr. Kint and son got ome…” There’s probably a troubling subtext

to the old Swede’s words. Yes, the two chee-chakers (tenderfoots as compared to

sourdoughs) got back – but barely. Probably a week or so earlier, Kent wrote to

his friend Carl Zigrosser in New York. (Letter dated Sept. with no date). He notes that the weather and seas had been terrible and Olson hesitated to make the

trip to Seward. “They strike us as terrible about the sea, here,” Kent

complained, “continually talking of frightful currents and winds in a way that

seems incredible to me and would, I think, to a New England fisherman. However,

I must be cautious. Olson says that in the winter for weeks at a time it has

been impossible to make the trip to Seward. Well, I’ll believe that when I try

it and get stuck. I’m full of courage now and life…”

He and

Rockie did “get stuck” and almost perished on the return to Fox Island on Sept.

24, 1918.

I have a working draft of a play

about Kent on Fox Island – “And Now the World Again.” It’s had a few successful

workshop productions. It’s a memory play. Sometimes the actors talk to the

audience, sometimes they’re embedded within a scene. At one point, Kent tells

the story of that treacherous Sept. 24th trip to the audience with Olson and

Rockie listening. Here’s a cut from that scene:

KENT

(To the audience) I’d been in

Seward for several days and longed for Fox Island. Let’s head home, I told

Rockwell.

ROCKIE

Row? Again?

KENT

Yes, son. Our engine still isn’t

working.

(To the Audience)

Some folks warned me about rowing

so far out in this weather, but I just smile.

OLSON

(To Kent) “Some” folks? I warn you.

I’m not just “some folks!”

KENT

(To audience) A few weeks back I

wrote to a friend: “They strike me as needlessly timid about the sea here,

continually talking of frightful currents and winds in a way that seems

incredible to me and would, I think, to a New England fisherman.

OLSON

(To Kent) To Hell with your New

England fisherman!

KENT

I’ll be cautious, Lars.

OLSON

( To Kent and Audience) Sometimes

in winter I get stuck for weeks on Fox Island, or in Seward. This bay can

deceive you.

KENT

(To Olson) When I get stuck, I’ll

believe you, I told Olson.

OLSON

(To Kent) Damn fool. Go ahead. Tell

them what happened when you didn’t listen to me!

We begin a dramatic retelling of

the story with both Olson and Rockie participating.

In that

same letter, Kent wrote to Zigrosser: “Have I written you about the island? I

can only think of it as a setting for a wild and stirring romance or rather story

of adventure.” Even after Yakutat and a few trips with an unreliable engine

back and forth to and from Seward, Kent still had an unrealistic, romantic view

of Alaska and the reality of its harsh wildness. He lived only 400 miles from

the Arctic Circle, he wrote to friends, and on Fox Island he wouldn’t see the

sun for months in the winter. Pioneer, sourdough Alaskans were “needlessly

timid about the sea.” A few months lobstering off Maine’s coast on Monhegan

Island may have made him overconfident. Every

year visitors to Alaska die with attitudes like his. Some who respect the

dangers and hedge their bets still perish. Alaska is no place for Kent’s kind of

arrogance. To his credit, he did learn and became more cautious.

You can

read his account of that Sept. 24, 1918 trip from Seward to Fox Island in Wilderness. It begins on page 20 of the

edition with my foreword. Beginning tomorrow, I’ll republish in two parts an

article I wrote for The Kent Collector about this incident within a larger

Alaska context, including reactions to the risks Kent took from experienced Alaska

mariners who know this area well.

PHOTOS

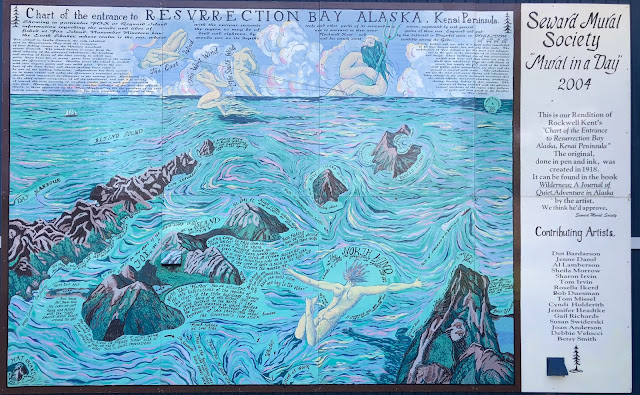

Seward has

been designated the “Mural Capital of Alaska” by the Governor. There

are many murals and visitors could spend a few hours on a walking tour to view them. Two murals are dedicated to Kent. This mural of Kent’s chart of the Chart of Resurrection Bay has been down for a few years for repair. It was

restored and is now back up.

In the same letter to Carl Zigrosser I mention above, Kent wrote: “ I’ll soon make a drawing of all this country, a birds eye map if I can, and send it to you.” Kent had finished it by Nov. 23rd. In Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern, Jake Wien writes: “Kent sent the completed Chart of Resurrection Bay to Carl Zigrosser in New York asking him to have fifty reproductions of it made on Bristol board and fifty on photoengraving paper.” Kent wanted Zigrosser to “Make them look the part of old maps – if it can be done in the printing.” Wien writes: “He {Kent} planned on having Zigrosser distribute some of them as Christmas gifts to close friends and family members.” When Kent returned to New York in the spring of 1919, the chart became part of the exhibit of Kent’s Alaska drawings at M. Knoedler and Company. When Wilderness was published in 1920, Kent used the chart for the book’s endpapers. “One reviewer found the work ‘fantastic and humorous,” Wien writes, “and believed the artist ‘retained his own individuality perfectly,’ even if William Blake had served as his spiritual advisor. Kent’s chart celebrated the Alaska wilderness, a majestic frontier that moved him to exclaim, ‘We are kings here, we and God!’” (p. 110)

In the same letter to Carl Zigrosser I mention above, Kent wrote: “ I’ll soon make a drawing of all this country, a birds eye map if I can, and send it to you.” Kent had finished it by Nov. 23rd. In Rockwell Kent: The Mythic and the Modern, Jake Wien writes: “Kent sent the completed Chart of Resurrection Bay to Carl Zigrosser in New York asking him to have fifty reproductions of it made on Bristol board and fifty on photoengraving paper.” Kent wanted Zigrosser to “Make them look the part of old maps – if it can be done in the printing.” Wien writes: “He {Kent} planned on having Zigrosser distribute some of them as Christmas gifts to close friends and family members.” When Kent returned to New York in the spring of 1919, the chart became part of the exhibit of Kent’s Alaska drawings at M. Knoedler and Company. When Wilderness was published in 1920, Kent used the chart for the book’s endpapers. “One reviewer found the work ‘fantastic and humorous,” Wien writes, “and believed the artist ‘retained his own individuality perfectly,’ even if William Blake had served as his spiritual advisor. Kent’s chart celebrated the Alaska wilderness, a majestic frontier that moved him to exclaim, ‘We are kings here, we and God!’” (p. 110)

This is one of the original copies of Kent's Chart of Resurrection Bay struck off by Zigrosser and is in my personal collection. Notice the stamp in the bottom right-hand corner. Jake Wien surmises that Zigrosser probably made 100 of these linecut reproductions but few survive in pubic and private collections -- perhaps 20. According to Wien, the original pen/brush and ink drawing has never surfaced. He theorizes that it may have been irrevocably damaged in the process of making the linecut reproductions. There are other original pen/brush and ink drawings by Kent, Wien notes, that have not surfaced in private or public collections, although there are linecut reproductions of them. Surviving copies like this one are relatively scarce.

The stamp in the bottom right-hand corner is Kent's personal stamp. This copy may have been owned by Kent.

Comments

Post a Comment