HAPPY VALENTINE'S DAY -- February 14, 1919 - 2019

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018

February 14, 1919 – 2019

HAPPY VALENTINE’S DAY!

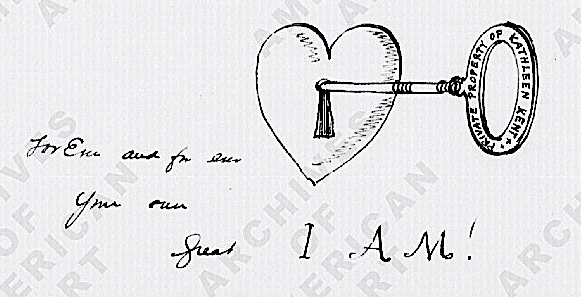

ABOVE – Kent’s

illustration at the end of his February 17, 1919 letter to Kathleen. “For Ever

and for ever. Yours ever Great I AM.” God uses these words in the Hebrew Testament, as does Christ in the New Testament. Kent did have a sense of humor, even in his elation and despair. His ego was huge but so were his doubts and insecurities.

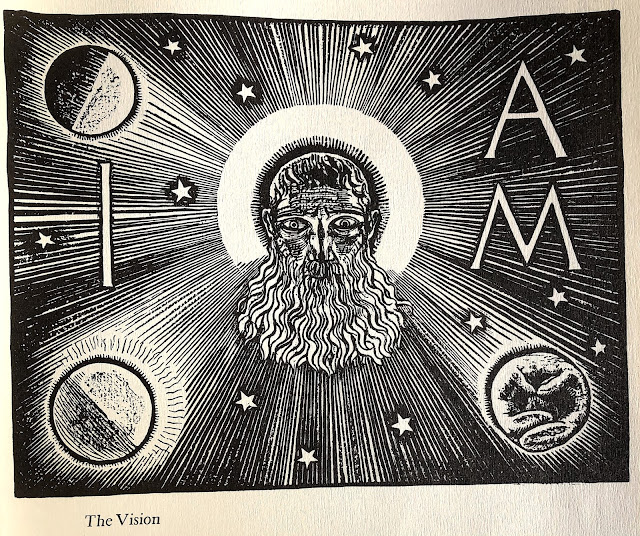

ABOVE - The last illustration in Kent's Mad Hermit series shows the hermit emerged from his cave having achieved truth and wisdom after much suffering and pain. BELOW – Kent’s illustration at the end of his Feb. 24, 1919 letter to Kathleen.

Written around the circle: “Big Rockwell & Kathleen like two good

sweethearts eating each other up.”

On this February 14, 2019 Kent writes in Wilderness: "The days go like the wind. So warm to-day and yesterday! We live out-of-doors." He feels forced to return home early and is in a rush to get as much sketching and painting done as possible. The cabin interior smells like turpentine as he stretches and primes canvas. In he afternoon he paints at the northern end of the beach "beneath a frozen waterfall, an emerald of huge size and wonderful form." With Olson's return their diet has improved. They running short and supplies and skimping. "We had to cut down on o0ur use of milk to a can in two or three days," Kent writes. "Now we may live on fish which Olson has in such quantities that we're to help ourselves." In thanks for Kent's taking care of the animals while he was away, Olson gives Kent a 50-pound sack of flour. Kent has also "borrowed" some of Olson's supplies during his six-week absence. He's been told not to worry about returning any of it. "What a contrast this free-handed country to the mean spirit of Newfoundland!" Kent writes.

Today Rockwell writes a ten-page letter to Kathleen. It is no Happy Valentine’s Day letter -- not even a mention of the occasion. He is “quite overcome” with Dr. Theodore Wagner’s offer of $2000, enough to keep him in Alaska for the summer. When he gets to Seward next he will write to Wagner. What will he say? “It is simply impossible for me to leave you alone any longer. I shall paint now with all my energy and try and get some good sized sketches done and then leave for home.” It’s clear he craves to remain in Alaska to see more of the territory and paint it. Why will he not accept this money? “Realize that my wife although she has promised to be true to me has also said that only the kindness of another man keeps her so – not her love for me – and that she still “craves men’s attentions.” Tell anyone what you have written me and ask whether after that I could leave you alone.”

Today Rockwell writes a ten-page letter to Kathleen. It is no Happy Valentine’s Day letter -- not even a mention of the occasion. He is “quite overcome” with Dr. Theodore Wagner’s offer of $2000, enough to keep him in Alaska for the summer. When he gets to Seward next he will write to Wagner. What will he say? “It is simply impossible for me to leave you alone any longer. I shall paint now with all my energy and try and get some good sized sketches done and then leave for home.” It’s clear he craves to remain in Alaska to see more of the territory and paint it. Why will he not accept this money? “Realize that my wife although she has promised to be true to me has also said that only the kindness of another man keeps her so – not her love for me – and that she still “craves men’s attentions.” Tell anyone what you have written me and ask whether after that I could leave you alone.”

Below

are the two revealing telegrams Kathleen sends to Rockwell in late January. He has

asked her to promise that she would be faithful to him, and to send him a

telegram with the specific words, “Yes, always.” After receiving his honest and

open anniversary letters on New Year’s Eve, Kathleen sends that telegram with

her promise on Jan. 26th.

Kathleen

receives and reads more of Rockwell’s letters and is annoyed. He has been

complaining about George Chappell’s influence upon her, and questions his true

friendship. On Jan. 30th she sends another telegram telling him to “be

content,” that she has given him her promise. Although Rockwell has demanded

she join him on Fox Island, he later equivocates and tells her he knows money

is a problem and leaves the decision up to her. In the second telegram Kathleen

decides they can’t afford her trip to Alaska, and then adds, “George is one of

your truest friends. But for him my promise could not have been given.” Rockwell is incensed that Kathleen’s “Yes,

always,” isn’t for her love of him – but because of George’s influence.

In

his Feb. 14th letter, Kent writes: “I’ve long determined that I am sorry for this lack of confidence.

Surely if I wrote you that I craved not you but other women’s love you

would hardly be comfortable. The past does not enter this, we speak now only in

the new present.” Apparently to Rockwell -- his past has been erased

because they have begun the “new present.” His affairs don’t count. Even though

he loved Jenny and Hildegarde, he still “craved” Kathleen’s love even more. But

Kathleen isn’t willing to accept his double standards anymore. If it’s all

right for him to accept the affections and love of other women, why can’t she

do the same? She won’t let go of that and it drives her husband mad.

As

he often does, Kent rereads this Feb. 14th letter over after he

finishes and adds a section along the side of the last page. He has rethought

the whole “George” episode and writes: “Darling,-

in reading over this letter I see that you may misunderstand my response to

George in regard to your promise to me. I mean nothing wrong there. I know that

it is his friendship and good cheer that you mean have kept you straight; but nevertheless,

I will not trust your soul to the friendship of another man. If you had said

that your love for me was too deep for you to think of, then I would have been

content. You realize don’t you the hideous danger that you have told me hangs

continually over your head? Be happy my darling. I’ll be back soon.”

Regardless of how he spins it, he doesn’t trust Kathleen. But Kent often can’t

seem to settle on a definite position. It must be quite confusing for Kathleen.

He loves her, adores her, even worships her as the ideal of womanhood –

but he doesn’t trust her to be faithful to him alone. He writes: “Understand little wife that I have a very

deep respect for your wisdom. Please be always better than I am. I want something

to worship. When I blame you, it is not as a woman but a rare heroine who

“nods” a little once in a while. I know it’s darned annoying to be worshipped

but that’s your job and you must just make the best of it.”

How

about his decision to return? Does he really “want” to leave Alaska? He dances

around that issue, too. On the one hand, it’s a firm decision and he tells

Kathleen not to try to change his mind. Yet, he still writes that they would

actually save money if she came to Alaska. If only he could be confident in her

faithfulness at home, he would stay – even if she didn’t join him. “I have seen nothing. I want to take the boat

and travel on the coast. Then I would have a rare and valuable experience and see

it. And you would be a true wife

caring for the children at home and resting in confidence in the hope of a

great outcome of it all for us. But that is now absolutely out of the question.

But if you would come, and gladly, above all things I’d like

that. We’d do it together and have a glorious time, a honeymoon, & how

wonderful. However, what’s the use of talking of it.” Just send me $450.00

and I’ll return as soon as possible, he tells her. “I am reconciled to it and have allowed my own hopes for reunion with

you to run wild. I want to come home. Can you understand me? After all I’ve done something here, maybe a great deal.” Maybe his work

in Alaska will result in success? Just maybe. He’s living on faith and hope. At

the same time, he’s setting up a narrative for his return in these letters.

It’s not my fault. It’s yours, Kathleen. If I could only trust you at home, I’d

stay. Or, you could join me. Those are the two choices. No excuses. You could

take one of the kiddies with you for free and settle the other two with your

and my mother. With Mr. Theodore Wagner’s support, the money would be there,

and you could rent out our apartment. We’d actually save money that way.

The

truth is – and Rockwell suggests as much in another letter – he is weak. He’s

lonely. Indeed, he’s homesick. And that’s not manly. The isolation, the

weather, the winds and rain and seas – the Alaska wilderness – has defeated

him. If all this became known, he could never get a patron for another venture.

I must add here that even today, I challenge anyone reading this to spend the winter on Fox Island. What kind of boat would you use. The dock has been taken out so at best you'd have to moor it off shore. But it's likely our winter north wind would break its mooring lines and you'd soon be without a boat. If you had a small boat like Kent's you could haul it up on shore and tie it down like he did, but then you'd surly not want to make the crossing to Seward in a boat like his. There's are cabins and some nice facilities out there but no electricity or running water in the winter. At least you'd have better shelter than Kent did. There is a wood stove in the day and overnight lodge. But you'd still be isolated. Even Kenai Fjords Tours rarely goes out there to check on the facilities. You would have cell phone service sometimes, or you could take a satellite phone. But could you take the isolation? Last night and today a fierce north wind roars and the mean temperature is about 10-15 degrees. It's clear with a bright sun, but no one is venturing out on Resurrection Bay. Of course, you could be rescued by our Coast Guard Cutter. But my point is people still die in these Alaska waters every year, and it takes very special individuals to live in the kind of isolation Kent found on Fox Island during 1918-19.

I must add here that even today, I challenge anyone reading this to spend the winter on Fox Island. What kind of boat would you use. The dock has been taken out so at best you'd have to moor it off shore. But it's likely our winter north wind would break its mooring lines and you'd soon be without a boat. If you had a small boat like Kent's you could haul it up on shore and tie it down like he did, but then you'd surly not want to make the crossing to Seward in a boat like his. There's are cabins and some nice facilities out there but no electricity or running water in the winter. At least you'd have better shelter than Kent did. There is a wood stove in the day and overnight lodge. But you'd still be isolated. Even Kenai Fjords Tours rarely goes out there to check on the facilities. You would have cell phone service sometimes, or you could take a satellite phone. But could you take the isolation? Last night and today a fierce north wind roars and the mean temperature is about 10-15 degrees. It's clear with a bright sun, but no one is venturing out on Resurrection Bay. Of course, you could be rescued by our Coast Guard Cutter. But my point is people still die in these Alaska waters every year, and it takes very special individuals to live in the kind of isolation Kent found on Fox Island during 1918-19.

“Put yourself off

on an island like this without the power or the means to return and you may

know despair,”

he writes on Feb. 15th.

On

Feb. 16th he solicits Kathleen’s support in his reason for

returning: “It will be somewhat hard to

explain this to our friends and I must ask you to let me tell the true cause.

If I said that I was tired of it or too homesick it would discredit me and make

it hard to get money for another venture at any time. For this money has been

pretty much wasted. I shall write to Dr. Wagner and to Carl and simply say that

you are in so despondent a mood that I cannot leave you alone and must come

home. Don’t mention my coming to anyone. I’m too ashamed of it. Please, dear, don’t put the blame for this on

me when you speak of it to others afterwards – unless you care at the same time

to tell them what you have written me and wired me. Please don’t misrepresent

my actions to Mother. Tell her simply that you have written me such blue letters

that it drove me to come back.”

On

Feb. 17th, Kent writes to his mother about the $2000 support offered

by Dr. Wagner: “Isn’t that wonderful? I’d

accept it at once but that Kathleen seems to be in{a}blue and despondent state

of mind that there’s nothing for me to do but return. I have written her to

send me the money for it. However if more gloomy letters arrive I’ll have to

wire for the money and return at once. The same day he writes to Kathleen: I repeat that you cannot well realize the

utter hopelessness of my situation here under the spell of unhappiness. There

is no relief and I approach insanity.” But it’s not that simple. Kent is

extremely ambivalent.

On

Feb. 18th he writes to Kathleen: “I

feel fearful at the thought of leaving this dear spot. I love it dearly and

shall all my life.”

On

Feb. 19th, “I’m very much

ashamed of my failure and fear that my supporters will lose confidence in me.

You know I am homesick and I do long beyond thought to be with you.”

On

Feb. 22nd, Darling, don’t

worry about my return. Write to me until you hear from me not to. Remember,

there’s no way of altering my decision.”

On

Feb. 25th, “Sweetheart, since

I landed here again I’ve done hardly one thing but think hard of you, so hard

that I wanted to be alone. I sent Rockwell out. I love you ever ever so dearly

and you must be a very happy girl till I get home and need no one else to keep you

good. Kent can’t get George Chappell out of his head. He’s the only one

keeping me faithful to you, Kathleen had told him. He’s the one who’s been

keeping me good, keeping me from straying.

On

Feb. 26th, “Olson came over

to-night to tell me that I simply must not go. He argues and argues

about it. Even says that my whole time here will have been wasted unless I

stay. As for me, I’m counting the days to when I’ll see you. And yet there’s so

much to do!”

To

his mother on March 9th, “In a

few days we leave the island…We’re both heartbroken about it. It’s the

loveliest spot I’ve ever been.”

{NOTE -- Kent is influenced by concepts of genius, heroism and manhood. He embodies early 20th century expectations of manliness. We see him trying to toughen up Rockie on Fox Island. Later he takes his younger son, Gordon, to Greenland. Kent can not conceive of retreating from Alaska because he couldn't live up to the male code of toughness. As I explore Kent's Alaska journey, I want to acknowledge the value of Suzanne Akhtar's 1995 Master's Thesis from Southern Methodist University -- Rockwell Kent's Vision of Twentieth Century Artistic Genius in Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska. It was published in sections during 2006-7 in The Kent Collector. In the Spring 2006 issue her chapter titled "Kent's Lone Man Figures and the Hermit Series -- Images of Artistic Creativity and Genius" is most interesting.}

A

100 years ago today, in that Feb. 14th letter, Kent writes about the

Christmas presents he receives upon Olson’s return on Feb. 11th. He

thanks his wife for the gifts but wishes she had actually made something for

him. “Stockings for Rockwell from Bessie

{Kathleen’s maid} and you came. They’re fine. But from your hand not one stitch

for me.” This sounds petty – and perhaps it is. But they are the words of

an artist whose gifts to others are often personal creative efforts -- sketches, drawings, unique Christmas cards. Later in the letter

he writes: “Remember darling always that

if a letter seems unkind my deep love for you is really in it. My letter

is that day’s drawing – and more. He expects Kathleen to ignore any

negative parts of his letters because each entire work is a product of his

creative spirit demonstrating his love for her. His tone is still sometimes as

parent to child, but not nearly as much. There seems a clear intent on his part

to be more positive. But, as Kent admits, when he gets in a foul mood his

negative thoughts just spew forth with no regard to Kathleen’s feelings. Quite

often, he’ll apologize immediately afterwards, but still leave the comments

there. Disregard them, he tells his wife. On a few occasions he writes that he

has torn up or burned a letter because it was too critical. He’ll return to her

what he considers the worst of her negative letters because he can’t stand

having them around the cabin. If they’re available, he can’t stop reading them

over and over again, sometimes marking them with responsive annotations.

Kathleen

has said she would send him copies of his Chart

of Resurrection Bay after Zigrosser makes copies. Kent hasn’t received them

and is anxious. He also wants her send him six sets of his The Seven Ages of Man portfolio that he left with Hildegarde. Kent is caught within a trap he himself as set.

He has ended he affair with Hildegard but he doesn’t want her hurt. “Don’t think that H. is appropriating my

things,” he tells Kathleen. I’ll

grant that she is very much to blame and very selfish about many things..but

she has been very good in carrying out all the little business matters I had to

leave in her hands. She took a pride in doing it and she holds on to some of the

things with a notion that she is in a sense my agent. And that is right. You

were away and could not have done the things. Please appreciate all this and be

faithful. So Hildegarde may have the Seven Ages. If she has, ask her to

send them to me or to let you but don’t let her think that I’m taking

these things away from her in anger, for I’m not. I am very grateful to her for

her care of them.”

ABOVE

– “Baby” from Kent’s portfolio, The Seven

Ages of Man, issued in July 1918 shortly before he left for Alaska. According

to Allan Antliff in his book Anarchist

Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American Avant-Garde (2001), the

series depicts “the abbreviated life of a soldier in four panels. Moving from

infancy through childhood to adulthood, a youth discovers the wonders of nature

and the beauty of love before dying ignominiously in the fourth panel on the

muddy battlefield of Europe. The portfolio cover featured a barren tree stump

blasted by lightening and a quotation from Shakespeare’s As You Like it: ‘And

one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.’ Kent’s naïve conscript,

however, only lived through four.” p. 150.

BELOW

– “Boy with Books,” “Love,” and “The Soldier” from The Seven Ages of Man.

Comments

Post a Comment