PART I OF 3 - THE FINAL ALASKA LETTERS

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

April 6, 2019

Part 1 of 3 – The Final Alaska Letters

ABOVE – Rockwell Kent and family in Vermont. The baby held by

Kathleen is their last child, Gordon, who was born Oct. 1, 1920. This photo was

probably taken in 1921. The oldest daughter, Kathleen is standing at left.

Clara is at far right, and Barbara is in the middle. Kent is standing at far

left and Rockie is in front of him. This photo and the others here are from the

Rockwell Kent Gallery, Plattsburgh State University, Plattsburgh, N.Y.

At this time 100 years ago, Rockwell and his son are on their

way back to New York. I’ve found no letters or postcards describing this

journey. Rockwell is anxious to get home, but he is also quite ambivalent about

leaving Alaska so early. Part of him is ashamed. Deep down he knows why he’s

departing early. It’s mostly because of his insecurities – his homesickness;

his need for Kathleen’s love and mothering; his fear that she’s on the edge of

finding another man to comfort her. He has hopes but is uncertain about how his

art will be received. There are no guarantees. The Alaska venture could fail as

did Newfoundland. In Alaska, Rockwell has also come face to face with intense

isolation. As they say – be careful what you wish for. He wanted to get away

from an unappreciative, money-hungry world at war – and to escape from both

Hildegarde and Kathleen. As Rockwell’s friend Carl Zigrosser wrote of him: “Rockwell’s life was punctuated by a series

of excursions to distant places—Newfoundland, Alaska, Cape Horn, the West Coast

of Ireland, Greenland and the like. The motivation of these journeyings was, no

doubt, complex: in addition to the lure of adventure, there might have been the

need in some instances, to escape from emotional entanglement.” BELOW -- Rockwell Kent in Greenland.

Rockwell

learns in Alaska, however that he can’t just sweep marriage issues under the

rug. One drags them along as extra-heavy baggage. He seeks solitude in Alaska,

but not the kind of near-exile he sometimes experienced on Fox Island. The

winter darkness in his small cabin pushes him into lonely letter-writing binges

late into the evening and early morning hours. He experiences the Hour of the

Wolf as well as a secular version of the Dark Night of the Soul. He has delved

deep into himself and to some extent sees his life in a new light – to some extent.

Like most of us, he’s more than capable of deluding himself, rationalizing how

deeply sincere is his motivation to change.

Rockwell promises to leave New York City upon his return not

only because he craves a rural isolation – but also because he must remove

himself from the city’s temptations. He promises Kathleen that his affair with

Hildegarde is over, but he doesn’t trust himself and pleads with his wife to

help him. He is sincere in wanting to save his marriage and knows Kathleen will

no longer put up with his affairs. Rockwell creates his own narrative

justifying reasons for his return – a story he asks Kathleen to accept so as

not to embarrass him and ruin future prospects for patrons. He relates this new

narrative to his mother in a letter. He’s leaving, he tells her, because of

Kathleen’s emotional state. She’s unstable and he doesn’t know what she might

do if he doesn’t return. Realistically, Kathleen has spent a good part of their

ten-year marriage on her own raising their children. She’s told him she can

take care of herself and not to worry. Rockwell convinces Kathleen to go along

with his narrative. He also makes sure his mother gets the correct story in a

letter. Rockwell Kent has mother issues. It’s not just that he needs his

mother’s financial support, he also deeply needs her emotional encouragement

and approval. Others have suggested that the death of his father when he was

five and his upbringing in a household of women influenced his psyche. Rockwell’s

mother, Carl Zigrosser wrote, “was very

forthright in her opinions, and was the only one in the family who was able to

stand up to Rockwell in argument. When Mrs. Kent heard that Frances {Rockwell’s

second wife} was getting a divorce from

Rockwell, she wrote Frances and congratulated her on having taken the step a

last.”

ABOVE -- Top

row from left: Kent as a child, photo inscribed to his daughter, Kathleen, in

1933; Auntie Josie Banker, Kent's mother's aunt. Kent's mother was raised

beginning at age 11 by her Aunt Josie and husband, James Banker on their estate

in Irvington, N.Y. Banker was a wealth capitalist connected with the

Vanderbilts; Kent's father, Rockwell Kent I, died when Rockwell II was five

yeas old. He's shown here with his flute which Rockwell inherited, learned to

play, and took with him on all his adventures. Bottom row from left: Kent's

mother, Sara Ann (Holgate) Kent with 3-year-old Rockwell at left and his

brother, Douglas at right; young Rockwell; Sara's sister, Kent's Aunt Jo, an

artist herself who took Kent to Europe for four months when he was 13 years

old. In addition to Kent's Austrian nanny, Rosa, (not shown here) who

taught him German, Kent was raised by the women in these photos.

Rockwell’s mother was probably more like her son than made him

comfortable. “It was only in this last

phase of her life that Rockwell respected his mother,” Zigrosser wrote. “He had become alienated from a way of life

in which she had grown up, and which he felt she represented, but now she

emerged as a personality rather than a symbol of background.” Remember, she

eloped with Kent’s father, Rockwell Kent I, knowing she would be written out of

her uncle’s will thus giving up a substantial fortune. She was a rebel in her

own right.

The following excerpts from the correspondence between Kathleen

and Rockwell from late February and March 1919 provide some interesting and new

information offering evidence for some of the claims I’m making.

Rockwell realizes he must choose, he tells

Kathleen (Feb. 23rd), between her and Hildegarde. His wife wins. Although

Kathleen has given him that ultimatum, he brushes that away and insists he’s

doing of his own accord. To “enforce”

that decision, Rockwell writes, “I would

leave New York and go into comparative seclusion…to devote myself to the

happiness and welfare of my family.” He urges Kathleen give him the love

that he desires. And what kind of love is that, among other things? Except rarely, Rockwell writes, you have withheld from me the intense

physical pleasure that is a very spiritual need of mine. Linked with a great

deal of romance of maybe my own imagination, I found that which I wanted and

lacked, in her {Hildegarde}. That was the reason of H. to me. It’s

clear, Rockwell needs to get away from the temptations of the city. But in any case, my leaving New York is a

precaution that must be taken almost regardless of other reasons for country

life. I want to be true to you, I want my desire to center upon you with

all its passion and

find forever such wonders coming in return, that for us both new Heavens will

have been revealed. On

March 17 Kathleen writes to Rockwell: In

my asking you to {not} to write H. I did it because I don’t trust her

and you don’t trust yourself either, for you saying it is necessary to {leave}

New York…you say you still love her and I know what a witch she is and that you

can easily be bewitched. If you didn’t want to be faithful to me, I

wouldn’t ask for that promise. Please don’t speak of my mistrust in you.

It brings to my mind many terrible scenes when you threatened me and

ordered me out of the house. Disturbing memories. But Kathleen believes

there is the possibility of restoring their marriage if she can keep Rockwell

out of the city.

ABOVE -- Hildegarde at upper left and lower right. Kathleen in center and at upper right with the children in Newfoundland. Fox Island cabin, interior and exterior.

As Rockwell has told Kathleen before, her

power over him is in her submission. (Feb. 24rd) But in your fear of my failure you shall not threaten me. You shall not

leave me. You must believe now as absolutely as ever in my faithfulness,

but above all in my love. I am looking for no outlet for myself, nor

excuse for future failure; that would truly be unworthy of me now; but we must

believe in each other now more truly than ever, to be more ready

than ever to hold to the other through thick and thin, and if one through

misfortune fails it must be for the other to reclaim. As you threaten to leave

me if I fail, I promise to follow you to the world’s end if you’re untrue.

And yet let me not hide what I believe to be the truth – there is vastly

more excuse for my unfaithfulness than for yours, there is more excuse for

man’s polygamy than woman’s polyandry. We are different regardless of

the assertions of the leaders of the woman’s movement of today. In saying this

I admit as I always have in this respect the impropriety of man in reaching the

best ideal of love. I do truly worship you, Kathleen. Your faith and constancy

of the past are my ideals of today. That you have been true is your glory, that

I have been false is my failure. Help me now and help me always. You can make

me true to you, but not by force. And I never will hold a threat over

your head. Now let’s believe wonderfully in each other. When it comes to

love and faithfulness, men are not as strong as women, Rockwell writes. Men are

weak, deeply flawed. His unfaithfulness is his failure. Men (he in particular) need

the absolute, complete love of women to keep them in line. BELOW -- Kent on his Tierra del Fuego trip, circa 1922.

Rockwell has established a narrative about

the reason for his return, one that puts the blame on Kathleen. It’s not his

homesickness nor is jealousy, he insists. It’s not even his distrust of her

faithfulness as much as it is her gloomy, depressed, unstable condition. He’s

afraid if he doesn’t return, she will slip into infidelity or worse. I’m

returning because I do still fear your relapses. Regardless of what you now

write I feel sure that you are not calm, and you do still have moments of bitterness

toward me and of desire to get elsewhere that truly I know you are entitled to.

And at these times it must be I who shall calm you…it must be

that you will never have such times and such happiness we now know only R.K.

right in your arms can bring you. Kathleen enjoys New York. She tells him that, although she'll be delighted to leave the city and live with him in their new rural paradise, she doesn't regret this time she has spent in New York. I believe it has energized her, given her more self-confidence and connected her to other women who helped raise her self-esteem. It isn't easy for her to face Rockwell in person and challenge him like his mother. His personality is too powerful. But in her letters she is able to tell him things doesn't dare bring up in person. Her months in New York City have also helped give closure to a professional career in music she might have had. And although I have no direct evidence for this, she suggests in letters that her friendship with George Chappell has provided the kind of intimate conversation she isn't able to pursue with Rockwell. This last fact disturbs Rockwell intensely. My guess is that Chappell has mentored her, counseled her about Rockwell's personality, his needs, his passions, his obsessions -- his overly romantic idealism and image of womanhood. We see Chappell counseling Rockwell about this in one of his letters.

After the new year, the Rockwell-Kathleen correspondence

shows a genuine attempt to honestly communicate with each other – but the time

and distance between the sending and receiving presents too many problems. Not

only that, but they both realize they speak different languages. They

misunderstand each other. Rockwell is sometimes so overt, willing to write

whatever comes to mind, regrets it, seems to retract it, but still leaves it in

– making it difficult to figure out precisely where he stands. He considers

even his cruel criticism of Kathleen a sign of his love. On Feb. 14th

he writes to her: “And now it’s almost

eleven. I must stop. I shall work furiously and write ardently and between

these have little time for more things. Remember darling always that if a

letter seems unkind my deep love for you is really in it. My letter is

that day’s drawing – and more. You need never feel downcast by anything I say.

I do want these letters to be happy ones and not scolding ones and I’m trying

to get all the scold out of my system at the start. If I were with you they’d

{there’d} be lots of kisses all through the scolding and we’d not think it a

bit an unhappy event, so darling feel yourself always, always dearly

deeply loved, and glow like a star even at the letter’s end.” Again on Feb.

18th, I don’t think you half

realize how much my letters to you mean to me, how I devote myself wholly at

the time of writing them to making them such as shall delight you. The time

I take away from my art to write my letters to you, Rockwell asserts -- that in

itself shows how much I love you. I throw my whole self into the letters. They

are extensions of me and my art. I’m writing you pieces of my soul, such as it

is.

ABOVE -- Kent and his family about 1915 after their return from Newfoundland.

On the other hand, Kathleen is insecure

about her ability to express her innermost feelings in writing. But she gets better in her February and March letters. She feels more

confident talking in person with Rockwell. He realizes that, and it’s one

reason he begs her to join him in Alaska. It’s the only way they seem to

communicate intimately. Add to this that Kathleen is fearful – probably from

past experiences – that if she tries to be open and honest in her letters to

Rockwell, he will misunderstand her words, read more into them than intended,

and become angry. She doesn’t feel she has the permission to be really honest.

She fears the unintended consequences. To a large extent she is correct. His

jealousy compromises his emotional stability. When he gets like that he isn’t

“happy.” That word appears frequently in both their correspondence. He wants

her to be happy so she will love him the way he wants. She wants him to be

happy because she knows how he can be when he not happy. His happiness is

connected to his self-confidence and to achieve that he needs her admiration

and assurance of his genius.

March 7, 1919 – Kathleen to Rockwell. She

has finally received a batch of 25 letters from that long period when her

husband and son were alone on Fox Island without Olson. There were 50 days-worth

of letters. She writes: I have been moved

to tears of happiness and then tears of despair, happy and despondent, happy

and despondent all day as I have read your letters. Why am I sad? Because you

misunderstand nearly everything I write. I don’t know whether it’s my fault or

yours…it is truly discouraging.

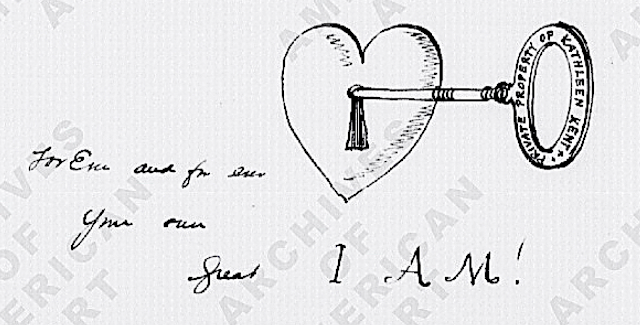

ABOVE -- Illustration from a Feb. 17, 1919 letter from Kent to Kathleen

TO

BE CONTINUED

Comments

Post a Comment