AUG. 6 - 9, 2019 PART 4: WILDERNESS & THE ALASKA PAINTINGS -- THE REVIEWS

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS

CENTENNIAL JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

Part 4 – Wilderness

& the Alaska Paintings: The Reviews

Aug. 6–9, 2019

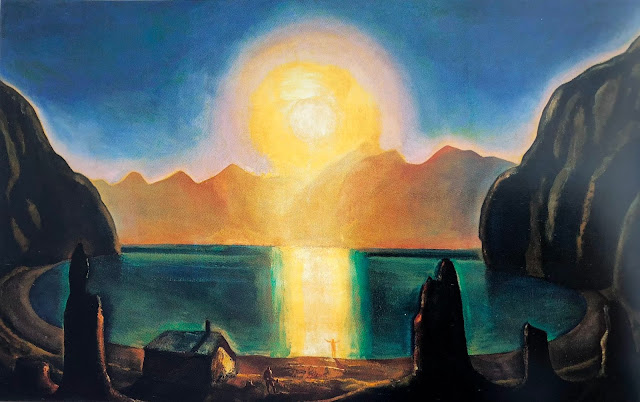

ABOVE – Pioneers (or, Into the Sun),

1919. Oil on canvas, 28 x 44 ¼ in.

I have just finished the life of Blake

and am now reading Blake’s prose catalogue, etc., and a book of Indian essays

of Coomaraswamy. The intense and illuminating fervor of

Blake! I have just read this: “The human mind cannot go beyond the gift of God,

the Holy Ghost. To suppose that Art can go beyond the finest specimens of Art

that are now in the world is not knowing what art is; it is being blind to the

gifs of the Spirit.” Here in the supreme simplicity of life amid these

mountains the spirit laughs at man’s concern with the form of Art, with new

expression because the old is outworn! It is man’s own poverty of vision

yielding him nothing, so that to save himself he must trick out in new garb the

old, old commonplaces, or exalt to be material for art the hitherto discarded

trivialities of the mind.

Rockwell Kent in Wilderness, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 1918

An early and important review of Rockwell

Kent’s Knoedler exhibition of his Alaska paintings appears in the Sunday, March

7, 1920 New York Herald. Henry McBride

writes:

The moment the doors were opened {Monday, March 1} the gallery was filled with the same old crowd of whispering, awestruck sensation mongers that one saw there last year, when Mr. Kent first came back from the frozen north with a bunch of Blakelike drawings under his arm. That May 1919 exhibition of Kent’s pen and inks was successful and had, indeed, created anticipation. What would be next? Would the paintings exceed expectations? Now it is a question of the oil paintings, McBride writes, and the dynamics are greater and the exclamations are greater. The frozen north is more austere even than we had imagined…

The moment the doors were opened {Monday, March 1} the gallery was filled with the same old crowd of whispering, awestruck sensation mongers that one saw there last year, when Mr. Kent first came back from the frozen north with a bunch of Blakelike drawings under his arm. That May 1919 exhibition of Kent’s pen and inks was successful and had, indeed, created anticipation. What would be next? Would the paintings exceed expectations? Now it is a question of the oil paintings, McBride writes, and the dynamics are greater and the exclamations are greater. The frozen north is more austere even than we had imagined…

ABOVE – Alaska

Winter, 1918-1919. BELOW – A winter scene from Fox Island of the possible

perspective Kent used for Alaska Winter.

Capra photo.

It’s no wonder the gallery was full. People

were curious about Kent – but he also tapped into the public’s curiosity about

the frozen north. Alaska has been in the news for many years, and most people

knew little about frontier realities. Many East Coast businessmen had

investments in Alaska. Myths about Alaska flourished back then. They still do today. William

Dall, a naturalist working in Alaska before the purchase had been publicizing

the possession’s value for decades. John Muir visited Wrangle, Glacier Bay, and

Tracy Arm in 1879 and wrote many articles about the northland. Steamship

companies began taking tourists up the Inside Passage by the early 1880’s. The 1898

Klondike Goldrush brought extensive notice and stampeders to the area. (Gold

was discovered there in 1896. All the important ground was staked in a month.

Word of the strike didn’t get out until 1897. The rush occurred in 1898.) Other

strikes followed in Hope and Sunrise on the Kenai Peninsula, in Nome, the

Tanana Valley and Iditarod country. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt

created the two largest national forest units in the country – the Tongass

(16.7 million acres) and the Chugach (almost 7 million acres). By the time Kent

came to Alaska, the U.S. clearly recognized the resource prize William H.

Seward purchased from Russia in 1867. Alaska had become a territory in 1912 and

given women the vote in 1913. The territory began pushing statehood bills in

Congress by 1916. Now, as Kent showed his paintings, the news was about much-needed

coal and opening Alaska’s interior to agriculture and other resources with the

construction of a new railroad from tidewater at Seward to Fairbanks. It was

not only financed by the federal, but they would also operate it. Never before

had the U.S. government run a railroad.

BELOW – Seward, Alaska circa 1915 – the

terminus of the new Government Railroad. Once completed in 1923 it became known

as the Alaska Railroad. Resurrection Bay Historical Society.

McBride’s review continues -- Some of the plump and sentimental ladies

among those present were sure that poor Mr. Kent must have suffered. M-m-m.

Perhaps he did. Why, even the waterfalls froze solid. Certainly Mr. Kent

suffered. Though possibly the paintings of them were worked up down here from

sketches.

ABOVE – Frozen

Falls, Alaska 1919. On Friday, Feb. 14, 1919, Kent writes in Wilderness: This afternoon I painted at the northern end

of the beach almost beneath a frozen waterfall, an emerald of huge size and

wonderful form. The waterfall BELOW is probably the

one in the painting. It fits Kent's description precisely. In other letters, he describes painting on the beach beside it. With all the rain

they had that year, it would have been quite a large frozen falls. Notice the two caves to the right and left of the larger of the falls. The perspective of the painting above looks like the view is from the entrance to the lefthand cave looking toward Bear Glacier to the south in the distance. If that's the case, Kent stood near the lefthand cave entrance or perhaps just inside the cave. If Kent used this waterfall, he was most likely looking northwest and moved Bear Glacier into the composition. From that spot, the south perspective would have blocked any view of the glacier. Capra photo.

McBride seems to acknowledge Kent’s suffering

in Alaska. Yet, not having read the personal letters between the artist and his

wife, he’s most likely referring to physical challenges with wilderness

survival. In a May 11, 1919 review of the pen and inks in the New York Herald,

McBride writes of Kent’s reading of Nietzsche and Blake. He has turned over other despairing pages and has gone out alone at

night to interrogate the heavens. But for all that, tragedy has not as yet

tinged his style, and it is impossible to be tragic over him or his work. Mr.

Kent’s life has not been tragic, but in spite of his own words, it has been

distinctly larkish. In It’s Me O Lord, Rockwell Kent looked

back from the mid-1950’s to his Alaska show and wrote of McBride’s review, noting

the critic observed that some among the

crowd felt that the painter must have suffered in the sub-Arctic cold – though

guessing (oh these critics!). Perhaps those plump and perceptive ladies who saw

suffering in the Kent paintings are more discerning than some of the critics. Either that, or they carried over those

conceptions from the year before when they had viewed Kent’s Alaska pen and

inks.

Those readers following this website who have

read the excerpts I’ve published from Kent’s and Kathleen letters to and from

Alaska, know how he did suffer. Granted, he brings much of the anguish upon

himself. But misery is misery whether self-inflected or not – perhaps worse if

it’s your own fault. We see Kent’s suffering mostly in the drawings. Most were probably conceived and/or completed

in the Fox Island cabin’s darkness, late at night and in the early morning

hours during the Hour of the Wolf. He doesn’t have enough light – between the

weather and the diminishing sunlight – to work on the paintings. The letters to

Kathleen written during these same dark hours demonstrate his pain and it seems

that finds its way into the drawings.

Out of curiosity, I went back to my transcribed files of Kent's and Kathleen's letters from Alaska. I did a search for variations of "suffer," "suffered" and "suffering." I gave up counting after a few dozen finds. It's clear that both went through a difficult time.

Out of curiosity, I went back to my transcribed files of Kent's and Kathleen's letters from Alaska. I did a search for variations of "suffer," "suffered" and "suffering." I gave up counting after a few dozen finds. It's clear that both went through a difficult time.

ABOVE and BELOW – Pen and Inks from Wilderness.

Shortly after his return home and move to

Vermont, we see the memory of that misery and the energy it produced evolve. On

June 22, 1919, Kent writes to Carl Zigrosser: I really think that every time and forever that I stand on these

hilltops {at “Egypt” in Vermont} I’ll

love life again as if it were all glorious. We see Kent beginning to heal.

On Sept. 2, 1919, Kent writes to Olson: I

can’t think of Fox Island without being a bit homesick. He’s only a bit homesick by the fall of 1919. By

this time he’s focused on his family, rebuilding his new home, and producing

his book. He’s had time to reflect on the success of his drawings and now he’s

more focused on the possibilities. He realizes the book’s publication and the

painting exhibition in early 1920 will be his moment for either success or

failure. He’ll soon be 40 years old. Always vigorous, he doubles down with the

vigor of a marathon racer to finish the book and the paintings. He uses that

stored negative dynamism to portray the idealism and romanticism of the quiet

adventure and inspiration he found on Fox Island. Forget the letters to Kathleen.

That’s over, that’s past, only part of the process. The wilderness tried to

defeat him, and at first he thought it had succeeded. But not anymore. He has

more than just survived. He has prevailed. He not only made it from the island to

Seward and back through treacherous seas, he also provided a safe haven and

memorable experience for his son. He made it home, and he hasn’t lost Kathleen

or his children. He uses his illustrated letter-journals as the basis for his

narrative.

BELOW – Rockwell's and Kathleen’s children in

Vermont, circa 1921. From left to right, Barbara, Clara, Rockie (Rockwell III)

holding Gordon, Kathleen. Kent family album, private collection.

NEXT ENTRY

PART 5

WILDERNESS AND THE ALASKA

PAINTINGS

THE REVIEWS

Comments

Post a Comment