SEPT. 18-20 PART 2 LARS MATT OLSON, HIS LIFE, AND HIS STAY IN VERMONT WITH THE KENTS

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL

JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

Part 2: Lars Matt Olson and His Stay in Vermont with the Kents

Sept. 18-20, 2019

ABOVE – This ad in the Feb. 28, 1897 issue of the Seattle

Post-Intellegencer showing Tom Boswell with his peg-leg, attests to the

reliability and accuracy of Lars Matt Olson’s memory. What we can’t be sure of,

however, is Olson’s assessment of Boswell’s character, although I’ve found

another article about him that gives us hints. Boswell was an early and

important prospector in Alaska and the Yukon. Read what’s below to learn of

Olson’s connection with the early prospecting of the northern frontier.

BELOW – Map of the area discussed in this entry, from Gold At

Fortymile Creek: Early Days in the Yukon by Michael Gates (1994)

NOTE – My recent research into Lars Matt Olson has more than

hinted at his significant place in the history of early prospecting in the

Yukon and Alaska. In these entries about him, I cover that information briefly

and with sources, but I don’t have time now to delve deeply into it. It has

more to do with Alaska history than with Rockwell Kent. But the connections

between the details of Olson’s stories – the ones he tells Kent – attest to the

trustworthiness of the old Swede’s accounts. Much of what he tells matches up

with known sources, and he may even be mentioned in other sources I’ve not yet

located.

OLSON OF THE DEEP EXPERIENCE

PART 2

I'm no admirer of the 'picturequeness' of

rustic character. Seen close it's generally damnably stupid and coarse. I have

seen the working class from near at hand and without illusion. But Olson! He

has such tact and understanding, such kindness and courtesy as put him outside

of all classes, where true men belong.

Rockwell Kent in Wilderness

We are

fortunate that Rockwell Kent not only listened to Lars Matt Olson’s stories

during his stay with the old Swede on Fox Island – but also recorded the tales

in his journal. However, everything in the original journal didn’t make it into

the first edition of Wilderness and

subsequent reprints. The story below was added by Kent in his 1970 special

edition of Wilderness, and you’ll

find it in the 1996 reprint by Wesleyan University Press. As you go through

that edition with my foreword, you’ll see in italics all that Kent added. Back

in 1920, his publishers probably thought information like that only had local

interest. They also cut quite a bit about Seward and its specific residents.

Kent added it back in. In 1920 he was happy to get the book out, and delighted

with its success – he didn’t have the fame to dictate terms to any publisher.

He later took great pains to see that his books were printed to his

satisfaction. It’s significant that one of the last actions of Kent’s life was

to see that Wilderness got reprinted

the way he wanted it. Some have questioned why the original foreword to the

book by Dorothy Canfield Fisher was left out of the 1996 reprint. The fact is

that Kent left it out of his 1970 edition. He was grateful for the help Fisher

gave him in finding and acquiring his Vermont property – but as one of his

letters to composer friend Carl Ruggles shows – her foreword had more to do

with the Putnam’s decision that her name would help sell the book. Fisher had

recently returned from France with her family when Kent arrived back from

Alaska. She had been aiding war refugees. A popular regional writer and

lecturer, she was much in the news at the time. Her foreword along with all the

editorial cuts, made the book – despite its subtitle – less of an Alaska book

than one about the simple life and wilderness in general and probably made it

more marketable.

Back in 1920

and through much of the book’s history, most reviewers, critics and art

scholars who wrote about Kent in Alaska, didn’t know much about the territory

in general or Resurrection Bay. There was an important Alaska and Seward

context to the book and the entire experience that has not been covered. Lars

Matt Olson is a part of that setting. He represents a breed of late 19th

century pioneers and prospectors who most often fade into dusty piles of

historical ephemera. Their figures and faces may be found in old, unlabeled

group photographs. We may discovery their names mentioned occasionally in the

local newspaper gossip columns. If we’re lucky we may locate an obituary, an

entry in a census document, or a marriage certificate. Olson is one of these

individuals, but one who, unknown to historians today, played a much more

important role in Alaska/Yukon prospecting history.

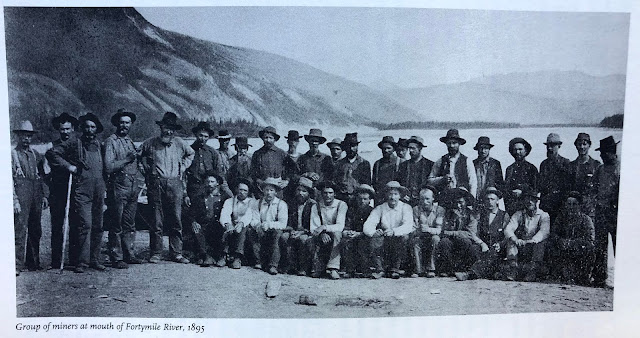

ABOVE – Miners

at Fortymile in 1895. For all we know, Olson could be in this picture with all

these other unidentified prospectors.

BELOW –

Fortymile along the Yukon River in 1896, both photos from Gold At Fortymile Creek: Early Days in the Yukon by Michael Gates

(1994).

This excursion

into Olson’s life isn’t a diversion away from the Rockwell Kent story. To Kent,

the old Swede symbolized the freedom, liberty and creative spirit of the

wilderness. The old man represented the kind of nonconformity admired by the

artist. Kent did complete at least one picture of Olson as did Rockie. On Monday,

Dec. 23, 1918 he wrote in his journal: I

finished a little picture of Olson and so did Rockwell…I have shown in my

picture the king of the island himself striding out to feed the goats while

Billy, rearing on his hind legs, tries to steal the food on the way. Rockwell’s

picture is of Olson surrounded by all the goats in a more peaceful mood.

Olson’s cabin is in the background. The whereabouts of these pictures is

unknown. Perhaps Olson kept them in his possession.

Like all

storytellers, Olson no doubt exaggerates somewhat – but I’m convinced the

essences of his tales are accurate. Many of the newcomers arriving in Alaska

during and after construction of the Alaska Railroad (1915-1923), didn’t

appreciate the history and experience of old timers like Olson. They gazed

forward toward growth, settlement and future statehood. To some, Olson was more

of an embarrassment, a symbol and image of a primitive past they wanted to

erase. The mythic and romantic was one thing – but Olson was too real. Seward’s

old timers and those in other parts of Alaska respected the contribution made

by those like Olson. They’d been around long enough to respect what it meant to

have prospected the Yukon and Alaska back in the 1880’s.

ABOVE – In

1916 the various “Igloos” of the Pioneers of Alaska met in Seward where this

photo was taken. Olson is standing at far right, recognized as one of the

oldest living Alaskan pioneers.

BELOW – Olson

in his cabin on Fox Island with one of his goats. Photo by Rockwell Kent,

courtesy of the Rockwell Kent Gallery, Plattsburgh State University,

Plattsburgh, NY.

In his book Gold At Fortymile Creek: Early Days in the

Yukon (1994), Michael Gates writes about these early gold seekers: Gold was discovered in California in the

late 1840’s. Subsequently, a succession of gold discoveries sparked stampedes

to new regions, each one farther to the north. Gold was found in Oregon, then

on the Fraser River in British Columbia, then in the Cariboo and on the Stikine

River in the central and northern part of the province. One of the results of

this series of gold finds was the evolution of a new breed, the prospector.

Ever seeking gold, impatient, moving on as new finds turned into productive mining

areas, always on the outer fringe of the mining frontier, the prospector was

always ahead of ‘civilization.’ It was not difficult for these men to eye the

unfilled spaces on the maps of the northwest and conclude that the gold

outcrops which had already been found would extend into those voids.

Lars Matt Olson,

one of those frontiersmen always on the outer edge, was born in Sweden in January

1848. We know nothing of the first twenty years of his life, at which time he

made his way to Liverpool, England and boarded the City of Antwerp,

arriving in New York City on June 15, 1868. The next eighteen years remain a

mystery. After he landed in New York, he probably headed West, eventually ending

up in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and San Francisco. He told Kent and his son his

memories of hearing about the Custer massacre at Little Big Horn in June 1876,

and about how trappers could train their horses to lead them back to their set

traps, even ones they’d lost. Olson also passed along other frontier wisdom:

“When a horse swims with you across a stream,” he advised, “guide him with your

hand on his neck, but pull not ever so little on the line or he’ll rear

backwards in the water and likely drown himself and you.”

{There

are many books about the Klondike Gold Rush. One of the best is Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush 1896-1899 by

Pierre Berton (1972). Some specific books that may be of interest include Captain William Moore: B.C.’s Amazing

Frontiersman by Norman Hacking (1993); George

Carmack: The Man of Mystery Who Set Off the Klondike Gold Rush by James

Albert Johnson (2001); and Gold Along the

Fraser by Lorraine Harris (1984).}

As Gates points

out, after the 1849 California gold rush, some prospectors headed north looking

for the motherlode. As often happens due to communication, travel and technology

-- those who arrived late to find newly discovered grounds all staked. They

could work for wages, start a business, or move on seeking their own strike.

Many trekked north to British Columbia where they discovered gold on the Haidi Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte

Islands) as early as 1850 and the Cariboo, Fraser and Stuart River rushes in

the 1860’s. John Muir traveled to Alaska in 1879 studying glaciers, calling the

world’s attention to what later became Glacier Bay National Park and Tracy Arm.

Prospectors out of Sitka discovered gold at what later became Juneau in 1880,

and a few years later steamships plied the Inside Passage with tourists. As

prospectors worked deeper into the area, they established frontier towns at

Forty Mile in the Yukon and Circle City in Alaska. Lars Matt Olson was one of

these early Alaska gold seekers. These early prospectors were on the ground in

towns like Forty-Mile and Circle City when gold was discovered in 1896 at Hope,

Sunrise and Nome in Alaska and in the Klondike in Yukon Territory. In Dawson,

all of the important ground was staked within a month. It took a year for word

to reach the states, and it wasn’t until 1898 that the actual stampede occurred

– the Klondike Gold Rush.

ABOVE – A

panoramic view of Main St. in Circle, Alaska taken in Sept. 1899.

BELOW – From

the Oct. 29, 1896 issue of the Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, an article about

life in Circle, Alaska.

Olson first

came to Alaska in the early winter of 1886-87, according to what he told Kent.

He and partner Louis Brown, a Norwegian named John, and a Tom Boswell arrived

in Juneau from San Francisco. Gold had been discovered in Juneau in 1880, and

Boswell had been there. Olson and his friends had met Boswell in San Francisco

that winter as he flashed around a $7000 poke of gold which he said he got out

of Alaska. Boswell knew the country,

Olson tells Kent, and knew where gold was to be found and the party followed

his lead. Who was Tom Boswell? Gates mentions him in Gold At Fortymile Creek: In 1882, fifty men came over the Chilkoot

Pass to prospect for gold. Twelve of them traveled downriver and wintered at

Fort Reliance with Jack McQuesten (this was only the second time McQuesten had

someone to talk to during the winter). The part included Joe Ladue, Thomas

Boswell, Frank Densmore, and George Powers.

ABOVE – This

article – from the Jan. 21, 1887 issue of the Victoria Daily Times (Victoria, B.C., Canada) is in all probability

about the Tom Boswell Olson writes about. Olson says he is flashing around

$7,000 in San Francisco while the article says it’s $6,000. Close enough! Either

the article is wrong, or this is Olson’s style of exaggeration – inflating minor

details.

BELOW – The

Palace Hotel in San Francisco, 1887.

From Juneau,

Olson tells Kent, a steamer took them to “Chilkoot,” a few miles below the

present site of Skagway. This may have been the location at the head of the Chilkoot

Trail that later became the gold rush town of Dyea. Once there, they met up

with other prospectors and decided to travel together. The first two out were

men named Carter and Mahon, who were returning to a promising place they had

located earlier. Kent interprets Olson’s pronunciation as “Mahon,” but it is

probably the Matt Mayon, mentioned by Gates. Olson’s party followed their new

prospector friends. They each carried fifty-pound packs with their personal

provisions up the Chilkoot Trail, except for one huge Frenchman they called

“Napoleon” who also toted three sacks of flour for a total of 150 pounds. Gates

mentions a member of that party known as the “Giant.” Also, McQuestion was

known as Leroy Napoleon (Jack) McQueston. Along the way their sleds broke, and

that evening they consoled themselves with a homemade brew containing “a whole

50 cent bottle of Patent Pain Killer!” From Lake Lindeman, they traveled

through Miles Canyon to the head of Hutlinana Creek (Kent calls it Hootalinkwa

River).

Carter and

Mahon were not anxious for Olson’s party to follow, not wanting to share an

earlier find. Caching their supplies a few miles from the river, both parties

started prospecting its banks. Along with Boswell, Olson was the only one with

any mining experience. John had been a trapper, so both he and Olson had a good

supply of traps with them. Louis had been a fisherman and goose herder. Boswell

seemed useless and Olson and the others were getting sick of him. He had been

in the country before, however, and was an experienced prospector – but he had

only brought a 25-pound sack of flour and some bacon, and was always sponging

off the others. Boswell headed upstream alone while Olson, John and Lewis

headed down. They caught up with Carter and Mahon who showed them a spot they

had abandoned earlier. Take it if you want it, they told Olson, so his party

panned out about eight dollars a day for a while, but decided to move on.

Boswell prospected the opposite side of the stream, hoping he would be asked to

join the others. One day, waving his hat, he shouted across the creek: “Come

on, boys, we’ve struck it rich.” His

find yielded $16 a day, but Boswell demanded a larger share for finding it. The

others refused.

ABOVE – Map of

the Klondike Gold Rush area.

BELOW –

Stampeders climb the Chilkoot Pass out of Dyea near Skagway, 1898.

“If you stake

this claim,” Olson told him, “we’ll move on. If you don’t stake it we will; but

make up your mind.” Boswell decided to stake it, so they left, following a

respectable distance behind Carter and Mahon to yield them first rights of

discovery. Louis and John both found good spots and staked them. Once they

reached Carter and Mason, they turned back and met up with Boswell – who now

had a different attitude. “Look here, boys,” he told them. “There are four of

us and only three claims, but let’s work them together and share alike. To be

sure, I have no grub, but since one of us has no claim let the man who can best

handle a boat go down the river in the spring and bring up grub.” The best boat handler was Boswell himself.

Winter would arrive soon, and savvy prospectors knew that working in groups was

not only safer but could also ward off loneliness. Boswell’s proposition seemed

prudent, so Olson, John, Lewis, and Tom Boswell decided to stay together for

the winter.

As I saunter

down Olson’s path to the lake and call out his name, I can imagine both Kent

and Rockie spellbound as the Swede related this tale. This special place at the

end of the trail still belongs to the old Swede and I believe his spirit

resides here. The Cheyenne remind us to

speak the names of our loved ones aloud after they’ve passed. Otherwise, they say, you’ll go crazy as your

tongue swells up – and then you’ll die.

I’ve always known him as Lars.

“I’m heading your way, Lars,” I say.

“Don’t let me interrupt whatever you’re doing.”

He’d

often walk this path to get his fresh water from a nearby spring, which spilled

down the mountain. Each winter, he’d lower his bagged summer pink salmon catch

(Humpy salmon) into the lake for storage.

As he needed fox feed, Olson wandered to the lake for fresh water and to

chop out the bags of salmon. After I announce my presence I stop talking and

listen. I can hear him lecturing one of

his angora goats that followed him down the trail. Olson loved those goats.

Many years ago Virginia Darling, daughter of T.W. Hawkins, told me she recalled

as a child watching Olson weeping while telling one of the store clerks the

story of how one of his goats had gotten into a can of paint, eaten some, and

died.

I know that Olson talks to himself often as well as to his goats and fox, to the

pink salmon as he catches them, to the river otters and the porcupine, to the

orca who rub their bellies on the beach, to the bald eagles, and to the

Black-Billed Magpies and Steller jays. Sometimes I detect a murmur, a wisp of

his words carried by the wind rustling above through the spruce and cottonwood.

OLSON'S STORY CONTINUED IN THE...

OLSON'S STORY CONTINUED IN THE...

NEXT ENTRY

PART 3

THE LIFE

OF LARS MATT OLSON

AND HIS

STAY IN VERMONT WITH THE KENTS

Nice historical detective work putting together the scattered bits and pieces of long ago, mostly, but not entirely forgotten lives.

ReplyDeletePersonal note: mention of Forty Mile reminded me of a segment of a long-ago expedition when two young guys took the road called by that name from Dawson City into interior Alaska. Recall they explored an abandoned gold dredge and took some now-lost photos posing on the weathered structure.

Bill

Thanks for the memory, Bill. For other readers, that was you and me -- almost 50 years ago.

Delete