SEPT 21-23, 2019 PART 3 OLSON IN NOME, ALASKA, AND HIS OTHER STORIES

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL

JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

Part 3: Lars Matt Olson and His Stay in Vermont with the Kents

Sept. 21-23, 2019

ABOVE – Olson mentions Tom Boswell quite a bit in the story I’ve

been retelling in the last few entries. Further down you’ll read about him

meeting Boswell in 1897 in Seattle, ten years after their prospecting trip into

the Yukon and Alaska. We can attest to the reliability of Olson’s memory from

this ad in the Feb. 2, 1897 Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Boswell is cashing in

on all his experience by selling advice to the stampeders flooding into Seattle

on their way to the Klondike Gold Rush.

OLSON OF THE DEEP EXPERIENCE

PART 3

Now having crossed the bay, thick wooded

coast confronted us, and we worked eastward toward a wide-mouthed inlet of that

shore {Humpy Cove}. But all at once there appeared as if from

nowhere a little motor-driven dory coming toward us. We hailed and drew

together to converse. It was an old man alone. We told him frankly what we were

and what we sought.

“Come with me,” he cried heartily, “come and I show you the place to

live.” And he pointed oceanward where, straight in the path of the sun stood

the huge, dark, mountain mass of an island. Then, seizing upon our line, he

towed us with him to the south.

Rockwell Kent in Wilderness, describing his meeting Lars Matt Olson on August 29,

1918 as he and his son explore Resurrection Bay in a borrowed dory seeking a

place to settle for the winter.

BELOW -- Lars Matt Olson's identification card for access to the docks in Seward. The Great War increased security along the port of Seward due to the importance of the construction of the new Government Railroad. Resurrection Bay Historical Society Collection.

If Tom Boswell

was to head down river for grub in the spring, he would need a boat. Olson used

a whipsaw and a small block plane to build a riverboat. He had no nails, so he

stripped the sled of its runners and cut out some. One day some of Boswell’s

friends, the “Montana Boys,” showed up.

“Come on

over,” shouted Boswell. “I’ve struck it fine, and you shall share.”

“What do

you mean by that?” Olson countered. “We’ve nothing to do with them.”

“I told

them that whatever I found I’d share with them,” Boswell told Olson.

“Well

then,” said Olson, “you’ll have to choose between us.”

Boswell chose

the Montana Boys. The two groups camped beside each other and started making

their rockers (sluice boxes). Boswell knew best how to make a rocker, but

wouldn’t share the information with Olson’s group. Olson closely observed him

working and learned the technique.

While the

Montana Boys worked with Boswell on his claim, Olson took his group up river to

the spot Louis had staked. Finishing work there, they headed further upstream

to John’s claim, but found it cleaned out by Boswell and the Montana Boys.

Olson later learned that Boswell and his group had headed up stream to Carter

and Mahon’s claim. They found the two clumsily hacking out a rocker with an

axe. “Don’t do that,” Boswell told them. “Go down to the claim we’ve left.

You’ll find slabs there that we’ve sawed out. With these, you can make…your

rocker.” With thanks, Carter and Mahon went down river to Boswell’s old claim,

collected the slabs, and headed back up river When they got back to their

claim, they saw that Boswell and his boys had cleaned it out. Carter was not

only angry, but he also felt foolish. He had known of Boswell’s reputation.

“He’s the greatest rascal in Alaska,” he later told Olson. “The money he took

out last year he stole from his partners on the Stewart River!”

ABOVE – I can’t

confirm the negative portrait Olson creates of Boswell. Maybe someone will

eventually find sources with evidence. I did find an article in the

Oct. 17, 1889 Butte Miner (Montana) that shows some thought Boswell guilty of

murder. The article quotes Charles B. Sperry, an engineer and minor who spent

four years in this area, including time at Fortymile.

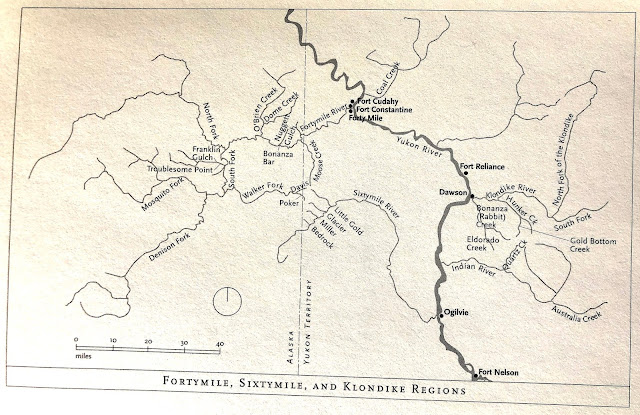

BELOW – Map of

the Fortymile area from Gold At Fortymile

Creek: Early Days in the Yukon by Michael Gates (1994)

Olson and his

group continued up river experiencing many adventures. Olson caught pike using

fishhooks he made from sled runners. He climbed a tree to escape a bear, only

to learn her cubs were up the same tree. He shot both cubs and carried them

back to camp. They killed a moose for the meat and loaded it in their boat,

which made it difficult for Olson to handle. Louis mocked him, so Olson turned

that operation over to Louis who recklessly overturned the boat – losing

Olson’s guns, blanket, all their gold and some of their grub. “If I’d had a gun

I’d have shot that fellow then,” Olson told Kent. They were eventually able to

recover some food and two guns. With most of their food gone, they headed down

the Yukon River to Forty Mile{sic.} over three hundred miles away. On the way

they met Carter and Mahon who gave them some sugar, flour and salt. One night,

hearing some splashing in the river, Olson roused the others and they found and

shot a moose. The meat saved their lives, but it soon began to spoil. They met up with some Alaska Natives who gave

them salt to cure the meat, which they traded for a 75- pound King salmon.

Finally, they reached Forty Mile.

ABOVE –

Restaurants and bars along First Avenue at Fortymile in 1898. Photo by Eric A.

Hegg: Univ. of Washington.

BELOW – Tom

Boswell had a brother, John mentioned below. He also had a brother named George who joins him prospecting. This notice from the Oct. 17, 1886 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle.

With little

more than some tobacco that Olson shared with his friends, the party survived

on one meal a day. Soon Carter and Mahon arrived at Forty Mile. After a while,

they learned that Tom Boswell, his brother, George, and one of the Montana Boys

named McCloud – had camped not far from the settlement. This would be John

McCloud mentioned by Gates in Gold at

Fortymile Creek, again verifying the accuracy of Olson’s story. Gates in

his book says McCloud arrived at Nuklukayet with Al Mayo in the summer of 1892.

In The Trading Trio of Arthur Harper, Al

Mayo and Jack McQuesten, Jane Gaffin describes Nuklukayet: A settlement at the junction of the Yukon

and Tanana rivers had supported a well-established Indian trading locality long

before the Europeans came on the scene. It was near what was later called

Tanana Station and where, in 1880, Arthur and Jennie Harper established an

Alaska Commercial trading post which was sometimes referred to as Harper's

Station but which he named Nuklukayet--probably under his wife's influence.

At Nuklukayet,

McCloud became suspicious of two other miners, Pitka and Cherosky, who had

arrived with $250 worth of gold and stocked up on tea, tobacco and calico. When

asked where they found the gold the two were silent, so secretive that McCloud suspected

they had found a profitable site, so he and two others followed them when they

left, hoping to find their location. The stopped at Fortymile where Pika and

Cherosky got blind drunk and told several of their discovery. The two later

built a cabin along the Yukon River and spent the winter there. Others built

around them, a trading post was established, and that place became known as Old

Portage. In the spring McCloud and others followed Pika and Cherosky and

they all prospected along Birch Creek to Squaw Creek to Harrison Creek – and

finally to Mastodon Creek and nearby Independence Gulch where they hit pay dirt (gold). That started a

stampede to what later became known as Circle. Jack McQuesten grubstaked

(financed) half the miners in Fortymile to work those creeks. This story

independent of Olson’s tale gives us another perspective of what was going

there.

BELOW -- Circle, Alaska in 1899, and the same scene in 2008. Source: Wikipedia.

Back to Olson’s

story: One night Carter took his double-barrel shotgun loaded with buckshot and

went after Boswell, but at their camp he found that Boswell and his group had

left. Olson later learned that after they left, Tom Boswell, his brother

George, and McCloud had “rolled” (robbed) the other Montana Boys of their gold

and headed to Nuklukayet, where they bought supplies from a storekeeper named

Fredericks and hid out on a nearby island. They build a cabin, “procured” a

native woman, and settled in. The “gold dust” Boswell had used to buy supplies

from Fredericks turned out to be a mix of copper and quicksilver with a little

gold to give it color. In those days, there was scant official law in Alaska. A

local miner’s meeting decided that Boswell had to repay Fredericks. “Mind your

own business,” Boswell responded, then prepared his cabin for a siege. The

other miners gave him a time limit to surrender or be attacked. Boswell

eventually gave in, but not until the siege had taken its toll. His brother George

was near death and others were ill. Olson later learned that Boswell led some

of his group to Russian Mission, portaged to the Kuskokwim River and got a

sloop. Heading to the

Bering Sea, Boswell eventually ended up in Unalaska and took a steamer to the

Outside (“Outside” is a term still used to refer to anyplace outside of Alaska,

usually the Lower 48 states). That winter at

Forty Mile, Olson recalled, 27 died of scurvy, including “Napoleon,” the giant

Frenchman. Olsen’s group took George Boswell, now a convalescent, downriver to

Nuklukayet to be tried for his crimes. George later made it to St. Michael, but

there wasn’t enough evidence to convict him.

(My research

indicates to me that what we’re getting here with Olson’s story is the kind of

inside information about what was going on during that period along the Yukon –

stories that just don’t make into the history books. Olson told these tales with confidence no doubt. They sounded authentic to Rockwell Kent because, as we can see here, he was authentic as were his memories.

Olson arrived

back in San Francisco in 1888 with his “little band of weather-beaten, crippled

miners.” As Kent retells it, “Olson was on crutches from scurvy, his beard and

hair were a year’s growth; all were in their working clothes, all bearded,

brown, free-spirited.

ABOVE – Article

about scurvy in the Yukon from the Nov. 1, 1888 The Victoria Daily Times

(Victoria, B.C.).

BELOW – Another

article about life along the Yukon from the Nov. 22, 1888 issue of the Tarborough Southener (Tarborough, North Carolina). Cases of survey are mentioned.

Arriving in San Francisco, each of

them carried bags, some containing up to $7000 worth of gold. Still dressed in

their old clothes, they visited the music halls “and drank gallons of beer.”

Because they spent so freely, all the girls in the upper boxes and balconies

wanted to join them. “Two days later,” Olson told Kent, “they were paid in coin

for their gold – by the mint – and all went to the tailors and got them fine

suits of clothes.” At the Chicago Hotel in San Francisco, the German landlady

was a “motherly woman who put all the grub on the table at once so you could

help yourself…” She told them: “You boys have some of you been in Alaska for

years and I know about how you lived. Now that you’re back you must have a

hankering for some things. Tell me whatever you want and I’ll get it for you.”

One of Olson’s companions replied: “I remember how my mother used to have

cabbage. I want you to get me one big head and cook it and let me have it all

to myself.”

Ten years

later in 1897, Olson met up with Tom Boswell in Seattle where, now with a

wooden leg, he managed an information bureau for prospectors. The year 1897

would be the perfect time to enter that business. Gold was discovered in the

Klondike in 1896. Word reach the outside in 1897. Prospectors flooded into

Seattle seeking advice, purchasing an outfit, and making travel arrangements to

the goldfields. The actual stampede would occur in 1898. In Seattle during

that winter of 1897, these “CHEE-chalk-ers” (tenderfoots) called Boswell “Peg

Leg Tom,” sat at his feet, absorbed his advice, and enjoyed listening to his

story about how a Polar Bear chewed off his leg. Some versions had him cutting

it off himself, Olson said; others claimed it had been amputated in Unalaska.

Olson learned that Boswell eventually led another group of prospectors North by

the Stewart River – to an old claim he called “Boswell’s Bar,” later known as

“Peg Leg Bar.” Finding no gold, he

started robbing Native caches but was found out. Escaping toward Dawson, he

learned that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) were after him and

disappeared into the wilderness. That was the last Olson heard of him. (A note on

CHEE-chalk-ers. You’ll almost always find it spelled “cheechalko.” Some of the

real old timers I knew (all dead now) – and one in particular – insisted that

the real sourdoughs pronounced it as I’ve spelled it, with the accent on the

CHEE.)

So, old Tom

Boswell lost a leg, chewed off by a Polar Bear? Or maybe he cut it off himself?

Sounds like one of those tall tales told by the old sourdoughs around the camp

fire to all the naïve CHEE-chalk-ers. Well – a newspaper ad and story confirms the

validity of Olson’s memory.

ABOVE – Peg-Leg

Tom Boswell in Seattle, from the Feb. 28, 1897 issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer

BELOW – The

story of how Tom Boswell lost his leg to a bear in the Nov. 2, 1891 Seattle

Post-Intelligencer. Rather than summarize the story, I’ll let you read it

yourself. Olson got it right -- even though it wasn’t a Polar Bear.

NEXT ENTRY

PART 4

OLSON TALE OF HIS

ADVENTURES IN NOME, ALASKA

AND A FEW OTHER OF HIS

STORIES

Comments

Post a Comment