OCT. 12 - 15, 2019 PART 8: LARS MATT OLSON IN VERMONT

ROCKWELL KENT WILDERNESS CENTENNIAL

JOURNAL

100 YEARS LATER

by Doug Capra © 2018-19

Part 8 Lars Matt Olson in Vermont

Oct. 12-15, 2019

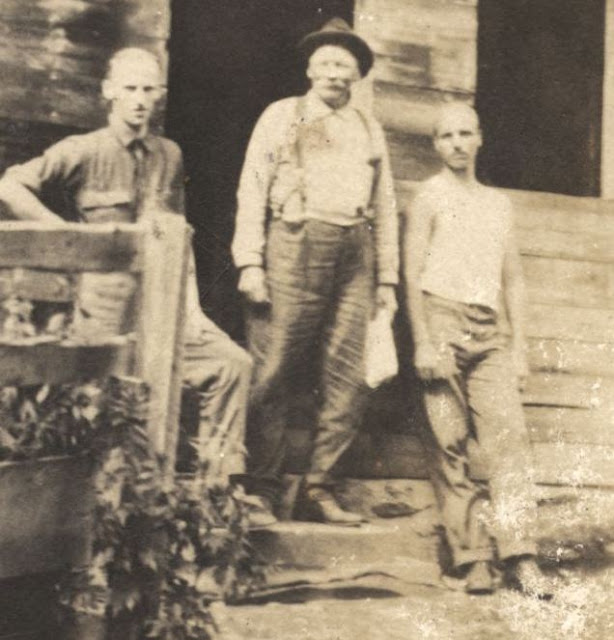

ABOVE –

Rockwell, Olson and Rockie in front of Olson’s cabin in Vermont. Photo from a

private Kent family collection.

ABOVE – Goethe by Joseph Martin Kraus (1775-6). Wikipedia photo.

ABOVE – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe by Joseph Martin Kraus (1775-6). Wikipedia photo.

OLSON OF THE DEEP EXPERIENCE

z

OLSON IN VERMONT

…the

highest pinnacle of harmony, perfection, contentment, and activity…

“In all provinces of

life, it is unhappily the case, that whatever is to be accomplished by a number

of co-operating men and circumstances cannot long continue perfect. Of an

acting company as well as of a kingdom, of a circle of friends as well as of an

army, you may commonly select the moment when it may be said that all was

standing on the highest pinnacle of

harmony, perfection, contentment, and activity. But alterations will ere

long occur; the individuals that compose the body often change; new members are

added; the persons are no longer suited to the circumstances, or the

circumstances to the persons; what was formerly united quickly falls asunder.”

― Wilhelm Meister

― Wilhelm Meister

Olson leaves

Seward via steamship on Friday, June 18, 1920. He arrives at Kent’s home in

Vermont fifteen days later on Thursday, July 1. While anxiously awaiting his

friend, Kent is reading Wilhelm Meister by Johann Wolfgang

Goethe. That truly thrills me, Kent

writes. He remains embedded within German romantic idealism and has a vivid

imagination which he depends upon to reconstruct his quiet adventure in Alaska.

Whatever he reads – Goethe, Nietzsche, Blake, Nansen, and especially Emerson

and Thoreau -- he absorbs fully and lives in that moment. Kent takes to heart

Thoreau’s words in Walden, or Life in

the Woods: “A truly good

book…teaches me better than to read it. I must soon lay it down and commence

living on its hint. When I read an indifferent book, it seems the best thing I

can do, but the inspiring volume hardly leaves me leisure to finish its latter

pages. It is slipping out of my fingers while I read…What I began by reading I

must finish by acting.”

In An American Saga: The Life and Times of

Rockwell Kent (1980), David Traxel summarizes the atmosphere at “Egypt”

during the summer of 1920: Kent’s energy

and ambition were too tempestuous for a placid country life, his desire for

experience and adventure too strong. He began to feel restless and confined.

It may have been that Kathleen’s passive

domesticity made him feel guilty, which increased his unhappiness. And Kent unhappy

was not Kent quiet, withdrawn, subdued. He reacted with anger, scorn and

slashing blades of criticism that cowed all around him. This was the situation

into which Olson had innocently walked. There were many reasons for his

mood at this time, but Wilhelm Meister may

have fed into it.

Kent had been

lonely, homesick, jealous and resentful while on Fox Island. He had also been

energized, productive, inspired and awestruck by Alaska’s beauty. He had never

been so isolated in his life, embedded within an indifferent, dominant

wilderness whose supremacy and authority both humbled and exhilarated him. Though

this isolation sometimes frightened him, it gave him the time to produce his

art. His idealistic view of what his new life would be with his family was

romantically naïve. Kent was a perfectionist. From thousands of miles away, an

isolated, rural life with Kathleen and the children seemed an Eastern version

of what he called his Northern Paradise. He hoped to create a different yet

equally satisfying version of Fox Island in Vermont, and Olson was part of that

scenario.

“A lovely, pure, noble, and most moral nature, without the

strength of nerve which forms a hero, sinks beneath a burden which it cannot

bear, and must not cast away. All duties are holy for him; the present is too

hard. Impossibilities have been required of him; not in themselves

impossibilities, but such for him. He winds, and turns, and torments himself;

he advances and recoils, is ever put in mind, ever puts himself in mind; at

last does all but lose his purpose from his thoughts; yet still without

recovering his peace of mind.”

― Wilhelm Meister

― Wilhelm Meister

BELOW – Minion

and The Harper (1923) by Paul Levere – from Wilhelm Meister.

At this point,

it’s worth reprinting part of a letter George Chappell sent to Kent on Fox

Island. Chappell was not only a close friend, but perhaps a father figure to

the man who had lost his own father at age five. Kent had been writing to

Chappell complaining about Kathleen’s unfaithfulness. He wanted Chappell to

intervene, talk with her, explain to her what Kent wanted from her, convince

her of her role in his life. Chappell had agreed to take care of Kent’s family

if something happened to him in Alaska, and he visited Kathleen and the

children frequently. Kathleen trusted him as well, and Chappell seems to have

sided to a large extent with Kathleen. He knew Kent too well. His siding with

Kathleen annoyed Kent, and he expressed this dissatisfaction in his letters to

both of them. Chappell was one of the few people who could confront Kent with

the truth, and he did that in a Jan. 12, 1919 letter. Kent receives this letter

on Fox Island after a stressful and productive period of uncertainty. Olson had left Fox Island on Jan. 2 to pick

up the mail in Seward and didn’t return until Feb. 11th. Kent and

Rockie, all alone on Fox Island, had no idea what had happened to the old Swede.

Kent had written two heartfelt letters to Kathleen in the fall and sent them to

Carl Zigrosser to be deliver to his wife with flowers on New Year’s Eve, their

10th anniversary. He had given up his relationship with Hildegarde, written

of his insight into how he had at times treated Kathleen with thoughtless

cruelty. He was a changed man, he assured her. Now – between Jan. 2 and Feb. 11

– he waited patiently for her response. Would she believe him? Forgive him?

Give their marriage another chance. Kent receives Chappell’s letter with the

mail Olson brings on Feb. 11. Here’s the Jan. 29, 1919 letter from George

Chappell to Kent:

“And please do try not to worry too much

about home affairs. It hurts me terribly to have you speak of Kathleen’s

‘faithlessness’; of how she has ‘shown herself up’ – It seems to me harsh and

unfair, when I see her at home giving unremitting care to the children, tied

hand and foot with daily drudgery that would make a man into a maniac in a

week, -- and always sweet and patient, always trying in her dumb, inarticulate

way to do what she thinks is her Duty. O, Rocky! Perfection is always the peak

beyond and the way to it is full of bruises, but we can attain a kind of

perfection by idealizing what we have and still not lose sight of the great

unattainable. You have much to think of with most precious comfort, much to

work for with great patience, much to come back to with supreme joy – if you

will only surround them with greatness of heart, with forgiveness for

short-comings, with tenderness and with -- unfailing love.”

“Men are so inclined to

content themselves with what is commonest; the spirit and the senses so easily

grow dead to the impressions of the beautiful and perfect, — that everyone

should study, by all methods, to nourish in his mind the faculty of feeling

these things. For no man can bear to be entirely deprived of such enjoyments:

it is only because they are not used to taste of what is excellent that the

generality of people take delight in silly and insipid things, provided they be

new.

― Wilhelm Meister

ABOVE -- Kent illustrated letter from the Archives of American Art.

BELOW – Kent and his family in Vermont, circa 1921. From left -- Kent with his arm around Rockie; little Kathleen; Barbara; Clara; standing in back row, Kent's wife Kathleen holding baby Gordon. Above and below photos courtesy of the Rockwell Kent Gallery, Plattsburgh State University, New York.

In Vermont

during that summer of 1920, Kent retains his perfectionist quest for that peak beyond – and as Chappell

predicts the way was full of bruises.

Traxel writes: Though he loved his

children, he expected of them the same energy, determination and drive for

perfection he had. When they became frightened by thunder he insisted that they

parade around the house banging on pots and pans. To some extent, Rockie

had experienced the same treatment on Fox Island. On Dec. 3, 1918, Kent wrote

to Zigrosser of his son: Certainly I tell

him this or that may do in some other person but not for him of whom I expect

better things as a matter of course.” When Kent’s expectations weren’t met,

Traxel writes, he punished with cruel

words if nothing else. The intensity of his anger could be terrifying, and his

scorn could cut like a knife. “Baby elephant,” he called an overweight

daughter. “Piano legs.” It’s difficult to assess Kent’s relationship with

his wife during that summer of 1920, but, according to Traxel, a vivid memory

of one of his daughters is of falling to

sleep, night after night, as her parents made beautiful music, father on flute

and mother at piano, the playing alternating with the sound of quarreling voices.

Kathleen would often be the target of his anger as he became more

dissatisfied. What did Rockwell and Kathleen argue about? Although hopeful in

the Alaska letters from February and March 1919, Kathleen seems still doubtful

about their ability to speak the same language. She blames herself because of

her inability to articulate her feelings in writing. She hopes that will change

when they’re together. But it’s also the case that when they’re together she’s

faced with Kent’s dominant and controlling personality.

“From youth, I have been accustomed to direct the eyes of my spirit

inwards rather than outwards; and hence it is very natural, that, to a certain

extent, I should be acquainted with man, while of men I have not the smallest

knowledge.”

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in Wilhelm Meister

― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in Wilhelm Meister

Kent’s

moods varied. He could be kind and then cruel, elated and then depressed,

energetic and then exhausted. He most likely blamed Kathleen for forcing his

early departure from Alaska by taking advantage of his homesickness and family

obligations. As the letters show, however, she obtained for him a $2000

patronage so he could remain in Alaska through the summer of 1919. She also

made clear to him that she would be fine with him gone, would remain faithful,

and could handle her motherly duties. He wasn’t convinced. Once in Vermont, he

longed for the creative solitude and freedom of Fox Island. In August (probably

1920) he wrote to Gerome Blume: Here {Vermont}

one is actually thrown back upon that

damned thing Imagination. Literally one has to imagine that there is loveliness

in the world, that all human beings are not physically deformed, slouch-gaited,

dull-eyed, dead-souled…I don’t like it a bit. New England! Kent continued

to paint, but the results didn’t satisfy him. On Aug. 13 (probably 1920) he

wrote to Carl Zigrosser: I wish there

were no other people in the world for a time, no horses or cows or mail service

or anything more in fact than one finds on a deserted island. Then I COULD

work. From Vermont, the intense solitude and agony he had experienced on

Fox Island seemed insignificant. At least there he had been able to focus and

get his work done.

ABOVE – The southern headland of Kent’s cove, taken from near the ruins of his cabin. Capra

photo.

BELOW – On Aug.

14, 2018 I visited Fox Island with producer and director Eric Downs shoot a

short film about Rockwell Kent. This is a still from a drone video done that

day by his cinematographer, Josiah Martin. You can see the western side of Fox Island with its two cove. Kent's cove is at left, Sunny Cove at right. Hive Island is at far right. To see some raw footage of the drone video, go to this link. The film is still in progress.

Despite

Kent’s attempts to turn Vermont into Alaska, it didn’t work. He had concentrated

on the romantic story in Wilderness.

His toxic, ranting, pleading letters to Kathleen, their debates and

discussions, and the personal struggle with his demons -- perhaps emerged during

the summer of 1920. And then there was Lars Matt Olson. From the time they met, Olson presented a

charming enigma to Kent, who noted that he understood and had worked with

individuals of all types and classes. I

have never known such a man," as Olson, he wrote in Wilderness, I'm no admirer of the 'picturequeness' of rustic character. Seen close-to

it's generally damnably stupid and coarse. I have seen the working class from

near at hand and without illusion. But Olson! He has such tact and understanding,

such kindness and courtesy as put him outside of all classes, where true men

belong.

Kent loved

Olson, but the old Swede relocated in Vermont, disconnected from his Fox Island

home, perhaps seemed unreal. That letter Olson had given Kent upon his arrival

– the one from Kent’s contact in Seward –noted how much the old Swede loved the

artist and wanted to help his career. Olson brought Alaska postcards to help

illustrated stories he would tell, while dressed in any old thing and acting in

any old way – playing the role as a curiosity

from the wilds. That would not be the authentic frontiersman Kent had

encountered on Fox Island. It would be a profane parody. And perhaps that’s how

it did turn out.

Kent is quoted

about the Alaska adventure in an interesting article by Zavier Lyndon in the

Sept. 4, 1921 New York Herald: I regard

the trip as the greatest event of my life. The quiet adventures that I recount

in ‘Wilderness’ are precious memories and frequently I am homesick for Alaska

and its rugged beauty. I brought back with me a glorious souvenir of the great

North – Olson, the aged Swede who shared most of my experience – Olson, the

pioneer of Alaska, who knows the country from end to end. He prospected for

gold on the Yukon, he was at Nome with the first rush there, he has trapped

along a thousand miles of coast, and now he lives with me at Arlington, Vt.,

where he spends good deal of his time marveling at the beauties of the country

and criticizing New Englanders, whom he regards as singularly lacking in energy

and enterprise. Yes, to him most New Englanders are decadents; he considers

them lazy people who are not taking advantage of their opportunities…And,

ancient mariner that he is, Olson still retains the maritime terms that have

always been a part of his vocabulary. He frequently amuses the neighbors by

referring to a ledge of rock as a reef; despite his failing eyesight, he can

see a goodly distance, he is in the habit of joyfully remarking that he can see

‘clear across the bay.’

BELOW – The

full article quoted above from the Sept. 4, 1921 issue of the New York Herald.

This wasn’t the

authentic Olson. This was Olson playing the part of the old broken-down

frontiersman – as he called himself – to the rhythm of Kent’s romantic

wilderness melody. The idea had been for Olson to live out his days comfortably

under Kent’s care. But things didn’t turn out that way. “Unhappily,” Kent wrote

in his autobiography, It’s Me O Lord (1955), Olson’s tenure of it {the cabin} and his stay with us were, by his own

choice, of but a few weeks’ duration. He went out west again, to end his days

with friends in North Dakota. Olson probably did choose on his own to leave

after he experienced Kent’s other side – the “anger, scorn and slashing blades of

criticism” – a part of the artist’s personality Olson had not witnessed on Fox

Island. If Olson didn’t live up to Kent’s expectations, neither did Kent live

up to Olson’s. Traxel says of Olson that, a few weeks after his arrival, after an angry exchange over the proper

weaning of Kent’s calf, the proud old sourdough packed up and left for his

youthful grounds in North Dakota. This part of the story always bothered

me. What had really happened between Kent and Olson in Vermont? Fortunately,

while searching through Kent’s correspondence on microfilm, I found an

enlightening letter from a Seward resident written to Kent back in 1967. Kent

answered the letter and I learned much more.

Art is

long, life short, judgment difficult, opportunity transient. To act is easy, to

think is hard; to act according to our thought is troublesome…One ought, every

day at least, to hear a little song, read a good poem, see a fine picture, and,

if it were possible, to speak a few reasonable words.

― Wilhelm Meister

― Wilhelm Meister

NEXT ENTRY

PART 9

LARS MATT OLSON LEAVES

VERMONT

HIS FINAL YEARS

Comments

Post a Comment